The Inundated City: A History of Seoul’s Failed Drainage System

https://doi.org/10.25542/ska0-pp14

On 8 August 2022, record-breaking downpours flooded Seoul. The deadly flooding shocked the public because it paralysed the Gangnam District, the nation’s wealthiest and most developed area. Murky water ruined the fancy commercial shops that lined the Gangnam boulevard. The undrained deluges flooded roads, leaving abandoned luxury cars floating around the submerged downtown. The flooding also destroyed some subway stations and temporarily suspended Seoul’s well-established subway lines. Seoul, the cityscape emblematic of South Korea’s compressed economic development, was completely inundated on that very day.

Although the media focused on the unprecedented heavy rainfall as the cause of the flood, the underlying problem is the long-standing failure of the urban drainage system. If we refer to historical records, low-lying riverside areas in Seoul, including the Gangnam District, have occasionally experienced flooding during the summer monsoon season. Almost every year, a series of typhoons hit the Korean peninsula with accompanied heavy rainfall, and when precipitation exceeds the city’s drainage capacity, it spells disaster. The problem is that the urban drainage infrastructure in Seoul is grossly underdeveloped and incapable of preventing flood disasters, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change.

Why does the nation’s most affluent city have a poor drainage system despite the long-term flooding issue? To answer this question, we must explore the trajectories of Seoul’s urban expansion after the Korean War. Alongside rapid population growth, the government reclaimed the lowland riverside areas of Seoul, believing that building large dams upstream of the Han River—the nation’s iconic river, which passes through Seoul—would save the city from flood risks. This misconceived faith in large dams allowed city planners to develop the area without a well-designed drainage system.

Flood Mitigation Measures for the Postwar Nation

Post-war Seoul suffered from chronic floods. Almost every summer, heavy rains cause the flooding of the Han River, affecting Seoul and the neighboring regions. For a poor country devastated by war, property damage and loss of lives in flood disasters posed serious threats. The floods that occurred in July of 1965 were especially disastrous as the flooded Han River completely submerged lowland areas in Seoul, leaving more than 80,000 people homeless and killing dozens of people.

After the disaster, then President Park Chunghee instructed related government bodies to devise countermeasures against flood damage. State engineers from the Ministry of Construction drew a hydrological flood forecasting diagram to predict the possibility of flooding in Seoul. However, this diagram was based on outdated colonial flood measures, which contributed little to flood damage mitigation.

The Korean government also collaborated with the Typhoon Committee, an intergovernmental organisation established under the joint auspices of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) to handle flood disasters in broader Asian regions. A team of six Japanese engineers visited South Korea to assist in the establishment of the nation’s flood prevention measures. After three weeks of fieldwork, the survey team recommended that South Korea enhance its flood forecasting capability to minimise flood damage. The Japanese team also suggested further analysis of rainfall patterns, installation of hydrological observatory stations, and the introduction of the telemeter system which would facilitate data transmission from water gauging stations across the Han River to the central office.

The Japanese team helped the Korean technical officers to design a flood forecasting network that calculated the risk of flood in downstream Seoul based on hydrological data gathered from the upstream river basin. When precipitation or water level records from the upstream river exceeded thresholds during inclement weather, state engineers would calculate the chance of flooding in Seoul and issue a flood warning. Considering the travel time of flood discharge between the upstream water measurement stations and Seoul, the forecasting system would allow people to have adequate time to prepare for flood damage before it reached Seoul.

As a preventive measure, state engineers also aspired to control the water levels in the river. An electronic plotting board was set up to show the river’s real-time water levels at various points, singling out the unruly river as a source of the floods and establishing the notion that flood management should include the control of the whole river, such as by containing water in the upstream river to protect the downstream river basin from flooding instead of building levees along the riverside.

Damming the River, Reclaiming the Riverside

Flood damage mitigation measures by controlling the entire river echoed the nation’s large dam projects in the same period. Lee Mun-hyeok, the Director of the Bureau of Water Resources, proposed a “Comprehensive Water Resources Development Plan” of multi-purpose dam construction for national progress. Inspired by the development of the wild Tennessee River Basin into an industrial region by the Tennessee Valley Authority, Lee believed that rivers can be engineered for economic development. He noted that South Korea had a relatively large amount of annual average precipitation of 1,100 mm which fell by two-thirds during the summer, causing destructive deluges. In order to deal with this, Lee proposed the building of large reservoirs to store the excessive flow of water during the summer and use the stored water for agriculture and manufacture during the dry season.

The authorities strongly supported the dam construction plan with the expectation that damming upstream rivers would also contain flood water, making downstream land development of the once flood-prone areas possible. A classic case is the Soyanggang Dam construction and the land reclamation of the Seobinggo areas in Seoul in the late 1960s. The Soyanggang Dam was originally planned as a small, single-purpose hydroelectric structure. However, the government re-designed it into a much bigger one to impound more water during the rainy season. Believing that the larger multi-purpose Soyanggang Dam would prevent recurring floods in downstream areas, the government then reclaimed 100,000 pyeong (1 pyeong=approximately 3.3m2) of the riverside Seobinggo District for residential development.

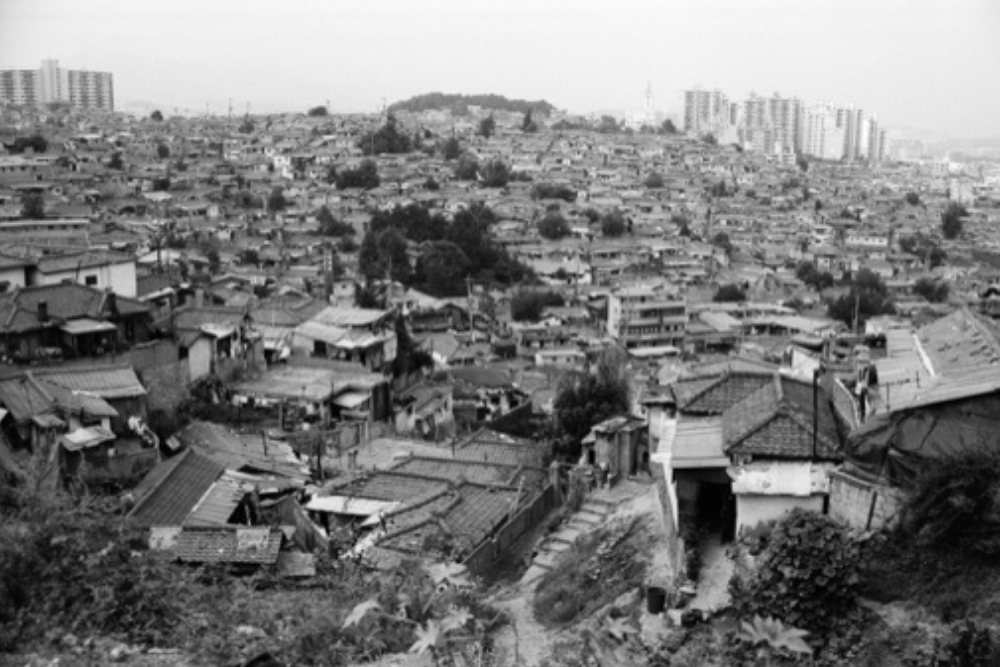

The Seoninggo reclamation project provided an effective business model for developing Seoul and South Korea. After the Korean War, the population in Seoul grew rapidly, rising from a million in 1953 to five million in 1970, which caused a shortage of housing and living places. To secure space for the expanding city, the government initiated a series of public water reclamation projects where riverside areas were filled to create more land for residential development. State-owned corporations, such as the Korea Water Resources Development Corporation, generated significant profits by taking part in these projects and selling reclaimed land to estate development agencies.

The Failure of the Urban Drainage System

Unfortunately, riverside reclamation projects exposed more people to the risk of flood disasters. A series of floods in 1972 showed that riverside land development could increase flood damage. Torrential rainfall between 18–20 August 1972 inundated riverside lowland areas in Seoul, taking 277 lives and leaving 230,000 people homeless. The floods in 1972 were extremely disastrous due to the heavy rainfall, but more importantly, the rapid urban expansion amplified the damage. Riverside land development narrowed the breadth of the Han River, making it more easily floodable. Excessive reclamation projects eradicated most of the detention basin that buffered the city from the flooded river.

Furthermore, the newly reclaimed riverside areas were not adequately equipped with water-draining facilities. Choi Young-bak, a professor of civil engineering in Korea University, stated in a media interview that “the biggest problem would be a lack of drainage capacity as sewerage facility coverage rate in downtown Seoul is about 30 percent, and in suburban Seoul is only 10-16 meters per hectare.” He further commented that “Seoul’s city planning is short-sighted. … Advanced nations conventionally do not permit construction in low-lying ground, in order to prevent urbanization in these areas.” As Choi noted, the reclamation projects transformed easily flooded areas into residential sites, but the city’s drainage capacity was only 30 millimeters per hour, while 50 millimeters of hourly rainfall was not unusual during the monsoon.

Despite the warning, Seoul continued to promote riverside reclamation projects during the 1970s. The famous Gangnam areas, in addition to Yeouido and Jamsil, were extensively reclaimed under this scheme. Large multi-purpose dam construction was at the centre of the flood management plan. The Soyanggang Dam, with 2.9 billion tons of water storage capacity, was completed in 1973, and another large Chungju Multi-purpose Dam was constructed in 1985 to contain a maximum of 2.7 billion tons of water upstream of the Han River. Counting on dam-building as a major flood prevention measure, the city turned the riverside into a symbol of modernisation with concrete apartments. Even in South Korea today, living in a high-rise apartment with a view of the Han River signifies prestige and wealth.

The flooding of Seoul in 2022 shows that the problem is far from resolved. Due to the overreliance on dam-building, Seoul has failed to take measures to improve drainage structures or conserve flood detention basins. Large sections of the city are still exposed to the risk of disasters but the good news is that Seoul has initiated the building of underground rainwater tunnels that can hold up to 110 millimeters of rainfall per hour. But rather than assume technological structures would solve the entire problem, a comprehensive study of whether Seoul’s urban development policy leaves parts of the city vulnerable to a disaster should be undertaken.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr. Seohyun Park is a postdoctoral fellow at the Asia Research Institute. He works at the nexus of science and technology studies, environmental history, and East Asian studies. His research explores engineering practices that shape human interaction with the natural environment in modern Korea and Asia. He is currently working on his book manuscript tentatively titled Dammed Nation: Engineering the Han River for Modern South Korea. He received his Ph.D. from the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at Virginia Tech.