Through a Glass Darkly: Misinformation about Health Online

Health is something most people would take to be of obvious importance. When we think of health, images of vitality, resilience, and perhaps also beauty immediately leap to mind. What is not to want? Indeed, the idea that health is valuable is so uncontroversial, that most do not notice that what each person means by “healthy” is often quite different in practice. Start up a conversation about veganism or the paleo diet, exercise regimens, or vaccines and things can get contentious pretty quickly.

Now add to this the speed of communication and data silos generated by the internet, and it is no wonder that misinformation about health is so rampant online. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought new attention and urgency to deal with the risks associated with viral misinformation and its public health and political consequences. In the wake of the pandemic, there was a storm of conspiracy theories and a growing market for medical pseudoscience and snake-oil salesmen. A survey conducted in Singapore in 2020 found that six out of ten people had received fake COVID-19 related news.

Misinformation on the web is rampant. Photo by visuals on Unsplash .

Misinformation on the web is rampant. Photo by visuals on Unsplash .

In the US, politicised information led some to believe the virus was a hoax, leading to unnecessary exposure and deaths. At the same time, others took extreme and misguided actions to protect themselves. After former US President Donald Trump made an offhand comment about hydroxychloroquine as a treatment against coronavirus, for example, one American couple ingested a form of chloroquine, an additive commonly used for cleaning fish tanks, thinking it would protect them from the virus. As a result, the husband died and the wife was hospitalised.

A New Spin on an Old Yarn

This overlap of conspiracy theories and health-related misinformation driven by COVID-stoked anxieties is not a recent phenomenon. The politicisation of health information has been around for centuries. As Frank M. Snowden observes in his book, Epidemics and Society, epidemics often exacerbate underlying social divisions present in the societies they afflict. The innate characteristics of pathogens, whether viral or bacterial, lend themselves all too well to the generation of conspiracy theories.

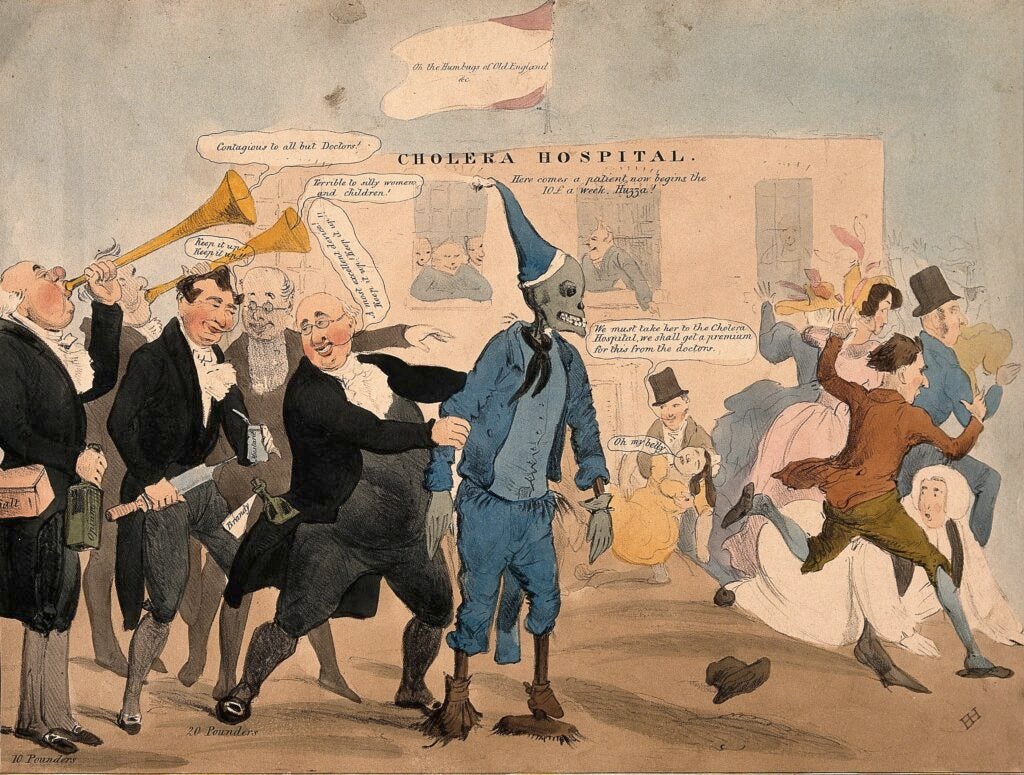

Take cholera which is primarily transmitted via the faecal–oral route. In the past, cholera outbreaks of the mid-to-late 1800s in Europe tended to affect poorer neighbourhoods which were less sanitary and more crowded. However, doctors who visited these areas rarely contracted the disease if they did not ingest anything contaminated. In a certain sense, they were “sociologically immune” – their health was preserved by the difference in standard of living and class experience. In the absence of any understanding of germ theory, class tensions naturally worsened, with some suspecting that it was a grand conspiracy by the rich to cull the poor and impoverished.

The cholera conspiracy of the 1800s. Credits: Wellcome Collection, Wikimedia Commons.

The cholera conspiracy of the 1800s. Credits: Wellcome Collection, Wikimedia Commons.

Thus conspiracy theories surrounding COVID-19 are hardly new or surprising. But familiarity and precedence should not indicate a lack of urgency. Misinformation about health must be addressed, as it undermines public trust, whether in government, the scientific community, medicine, or public health agencies. In turn, a lack of trust makes people less compliant with legitimate health and safety guidelines, leading to reckless actions that expose themselves and others to unnecessary risk. Health misinformation also has the ability to cross borders, such as the infamous fraudulent study by Andrew Wakefield, which purportedly found a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Though long discredited and debunked, its claims are often cited in anti-vax circles across national boundaries.

Misinformation related to COVID-19 is even harder to combat. Shawn Goh, a researcher of online misinformation at the Institute of Policy Studies, Singapore, names four Vs driving this trend: “The sheer volume of vaccine misinformation circulating; the velocity at which they spread; the variety of forms it takes, diverse countries and origin and platforms they circulate on; and the visceral feelings of fear and anxiety evoked by vaccine misinformation that cannot simply be legislated away”. Misinformation is fuelled not only by new technologies that make communication faster, but also by our human tendency to reason emotionally and socially. What we are facing is not just a physical threat of infection, but a crisis of medical literacy and public trust.

Cognitive Bias and COVID-19 “Conspiracies”

When it comes to COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy, much of the problem seems to overlap in the realm of conspiracy theories. Some worry that the mRNA vaccines will cause infertility, while others fear that the vaccines will be used by Bill Gates to somehow control or track them. What is behind the spread of such claims?

The answer may lie in uncovering our common cognitive biases and epistemic vices. Psychologists have identified many cognitive biases to which we routinely fall prey. Confirmation bias explains why people already distrustful of the government are susceptible to stories depicting the government as untrustworthy, and the availability heuristic shows why people readily accept unreliable information disseminated on social media as it is abundant and served to them without much effort. Then, there is the Dunning-Kruger effect—a cognitive bias in which people overestimate what they are capable of. This concept suggests that the more confident in their abilities or knowledge a person might be, the less of either they in fact possess.

Adding to the research on cognitive biases is the emerging subfield of philosophy, vice epistemology. Epistemic vices are more than mere errors of thinking; they are errors which in their structure make themselves more difficult to detect and remedy (thus leading to the “vicious” cycle, which gives them their name). To illustrate, arrogance can be an epistemic vice because an arrogant person is unlikely to see the ways in which their own arrogance hinders them—and they are unlikely to detect this because of their arrogance. An arrogant person is prevented from error detection and correction, and consequently, is less likely to improve or overcome this problem. Epistemic vices are character failings, but unlike other character flaws (such as gluttony or greed), they interfere directly with their own remedy. Besides arrogance, philosopher Linda Zagzebski (2020) identifies: “negligence, idleness, cowardice, conformity, carelessness, rigidity, prejudice, wishful thinking, closed-mindedness, insensitivity to detail, obtuseness, and lack of thoroughness”. Meanwhile, Quasim Cassam (2016) proposes another list that includes gullibility, dogmatism, prejudice, closed-mindedness, and negligence.

Arrogant people may fail to see how their arrogance affects them. Shutterstock.

Arrogant people may fail to see how their arrogance affects them. Shutterstock.

Experimental studies of both online and offline spreading of rumours also document a tendency of the propagators’ bias to be written into the narrative. Every time a story is transmitted, some original information is lost and other additional elements are added, and these elements often reflect the interests and biases of the propagator. Other studies of online urban myths have shown that attempts to debunk aspects of rumours as untrue are frequently thwarted by the spreaders of the myth claiming that the heart of the issue is a “deeper” (perhaps metaphorical) “truth,” usually one that resonates with deeply embedded historical grievances.

Finally, a 2020 study by the National Centre for Infectious Diseases in Singapore shows that vaccine hesitancy and a tendency to share misinformation online seem to be more common among those in lower income brackets and with lower levels of educational achievement among its participants. Other studies carried out in other countries have found that vaccine hesitancy is highest among women and minority groups. Some of these trends are unsurprising since one might assume that being less educated, for example, makes one an easy prey to misinformation. But more intriguingly, why should women, minorities, and those with lower income be especially susceptible?

Trust: A Missing Puzzle Piece?

Here, the issue comes down to trust. In the history of medicine, women and minority groups have often struggled to have their pain recognised and concerns addressed. The feminist philosopher, Miranda Fricker (2007), calls this phenomenon epistemic injustice, the prejudice that causes certain groups to be not recognised as “knowers” in the same way as their peers. For example, there is a prevailing tendency in medicine to dismiss a woman’s complaints of chest pains because “women complain about everything,” while tending immediately to a similar complaint from a man.

At a more macro level, a similar pattern of epistemic injustice and mistrust has grown out of the history of European colonialism in Asia and other parts of the world. When viewed in the historical context of disempowerment and domination by outside political forces, the level of vaccine hesitancy (whether for polio or COVID-19) in countries like Pakistan, and mistrust of humanitarian health interventions (especially when they come from Americans or other Western powers), become more understandable. This history of epistemic injustice in the medical establishment contributes to a lack of trust in medical and scientific institutions, making people less likely to accept the information as authoritative and thus less likely to comply with guidelines as well. If we treat the problem of misinformation purely as an intellectual failing on the part of the misinformed, we compound this pattern of epistemic injustice and contribute further to the rift in trust.

Vaccine hesitancy is rooted in historical injustice. Photo by Mufid Majnun on Unsplash.

Vaccine hesitancy is rooted in historical injustice. Photo by Mufid Majnun on Unsplash.

Trust in the medical establishment is undermined by two additional factors—a high degree of epistemic opacity and a low degree of epistemic empowerment. Like quantum physics, the realm of medicine is often counterintuitive and mysterious, especially for patients who do not share the physician’s expertise. In addition, medicine and public health often treat the people they serve as passive entities (the word “patient” comes from the Latin “patiens”, meaning to suffer or to bear). Alan Levinovitz (2020) uses the analogy of passengers on a plane to explain why the combination of epistemic opacity and the lack of epistemic empowerment is so frightening. When we fly, we are seated in a passive position, the pilot and his instruments are hidden from our view. Because we have no ability to fly the plane ourselves, we feel powerless to save ourselves should anything go wrong. As such, many people fear flying for the very same reasons they mistrust medical and public health institutions.

It is this very opacity and epistemic mistrust, along with all the biases and vices we come pre-programmed with, that makes misinformation about health so easy to spread and so difficult to combat. But what should we do about all this? And where does that process start?

The answer depends on how we frame the source of the problem. If we think of it as mostly a result of poor individual critical thinking skills, then launching education campaigns seems the obvious way forward. There are certainly many reasons why people may have inaccurate health beliefs. Knowledge about good nutrition, healthy lifestyle choices, exercise, and risk factors, etc., are not innate, and are far from obvious or intuitive to grasp. Eating your vegetables because your mother told you to is simple enough, but understanding risk factors for diabetes is more complicated. More complicated still is assessing the risks posed by a novel virus. It took years for medical science to reach its present stage and even now it has yet to explain everything we would like it to. However, to counter the negative effects of epistemic opacity (which provokes feelings of vulnerability and mistrust) we still need to promote epistemic empowerment by increasing literacy in science and medicine.

But increasing literacy alone will not solve the problem. My research thus far leads me to believe that the individualistic approach of fighting online misinformation neglects a vital piece of the puzzle—namely, the importance of trust and the need for reconciliation between the institutions of public health and the people they are meant to serve. What these individualistic strategies miss is the relational dimensions of the spread of misinformation: specifically, the role that the history of epistemic injustice plays in creating a rift in trust between the public and the institutions that should exist to serve it. Forging a different relationship between institutions of medicine at the interpersonal, clinical, or global level, would go a long way to mitigate the appeal of health-related conspiracy stories and medical misinformation.

Literacy and trust between people and institutions are critical. Shutterstock.

Literacy and trust between people and institutions are critical. Shutterstock.

It is no coincidence that those most at risk of falling for misinformation are also those already distrustful of “the establishment”, often with legitimate reason. Historical breaches in trust as well as gaps in power and knowledge fuel this feeling of mistrust, and as long as that rift in the relationship between institutions and the public they serve persists, the misinformation pandemic will continue to plague us.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Dr. Kathryn Muyskens is a political philosopher by training, with special interests in the politics of health and medicine – especially at the global level. She received her PhD from the Nanyang Technological University. Her research focus is on human rights, international politics and health. She has always hovered at the boundary between philosophy and the social sciences and always aims to find the connection between theory and practice.