Vocabularies of the Bandung Spirit: ‘Intervention’ and the Asian-African struggle against apartheid

https://doi.org/10.25542/s62g-ax04

What does it mean to ‘intervene’? The word is extremely common in international politics. Following from the principle of state sovereignty, the duty never to intervene in the essentially domestic affairs of others is a cornerstone of international law and society. And non-intervention is a core vocabulary of non-alignment and the Global South project, ideas experiencing a resurgence in world politics today. It might therefore be tempting to trace the modern practice of non-intervention to the watershed Asian-African Conference hosted in Bandung, West Java, in 1955, when 29 Asian and African countries came together to imagine a more just global order based around sovereign equality.

Yet the Bandung Conference also involved a unified stand against human suffering that transcended state borders. All participating governments declared their international solidarity, to take just one example, against apartheid in South Africa. Hence what diplomats would later call the ‘Spirit of Bandung’ might appear to bear out a tension in the lexicon of the non-aligned world: any proclamation of unconditional non-interventionism that, at the same time, extends international support for victims of gross violations of human rights abroad, would seem to be a confusion, a contradiction in values. Not properly so, as I explored in my ARI seminar on this topic in late August 2024 and lay out here.

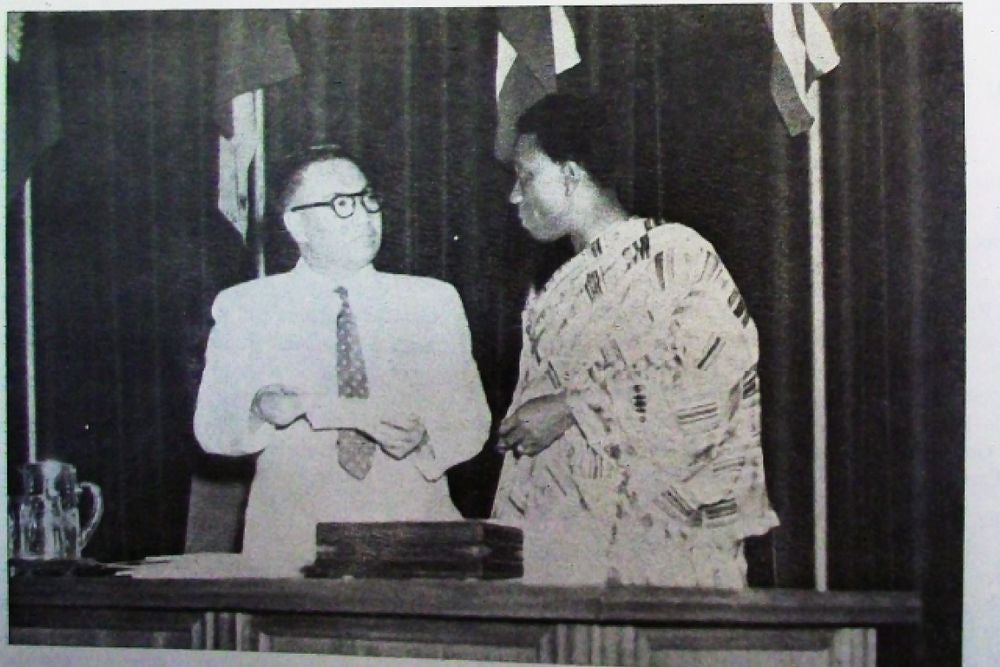

Asian-African Conference Secretary-General Roeslan Abdulgani (Indonesia) and Head Delegate of the Gold Coast (Ghana) Kojo Botsio, Bandung, 1955. Photo credits: Asian-African Bulletin.

Asian-African Conference Secretary-General Roeslan Abdulgani (Indonesia) and Head Delegate of the Gold Coast (Ghana) Kojo Botsio, Bandung, 1955. Photo credits: Asian-African Bulletin.

The classical definition of intervention in International Relations refers to ‘coercive’ or ‘dictatorial’ interference, usually understood to refer to the threat or use of armed force. This is a theory reflected in the writings of Western jurists like T. J. Lawerence and Lassa Oppenheim. And it is inherent in the concept of ‘humanitarian intervention’—a pillar of the so-called ‘Liberal Global Order’ in an era now passing or passed—that refers to the threat or use of armed force across borders for the prevention of large-scale human rights abuses. But how would our understanding of the global 'sovereignty-intervention' debate change if we were to reveal competing definitions of these concepts at different times, and in different places?

The historical struggle against apartheid clearly did involve international action, including by particular forms of coercion, to prevent large-scale human rights abuses and mass atrocities abroad. But it would be wrong to explain that struggle in terms of international intervention or as an infringement of the equal right of all states to sovereignty, a right widely recognized, then and now, as indefeasible though not unqualified by international responsibility. At the Bandung Conference it was proclaimed the duty of all states never to intervene in the domestic affairs of others, for any reason, in whatever form. The protest of what soon came to be known as the ‘Third World’ or ‘Global South’ was clearly against intervention—even ‘intervention’ for higher purposes or in conscience-shocking circumstances. Yet a ‘Bandung theory’ of the intervention concept was and is not just about whether to intervene. Rather, it is about what is intervention.

A sketch of ‘what it meant to intervene’ at Bandung could be made in three key steps.

First, borrowing from traditions of thought in Latin America, particularly the writings of the 19th-century Argentine legal scholar Carlos Calvo, ‘intervention’ at Bandung referred to the effect or outcome of foreign pressure. Here the range of international activities prohibited by the duty of states never to intervene went further than force, spanning economic sanctions, tied aid, debt traps, foreign propaganda, foreign incitement of rebellion abroad, and various other forms of censure or speech, for example. Bandung’s vision of non-intervention therefore approximated an understanding of ‘freedom’ as more than freedom from coercive interference. Such a vision had come to be reflected in the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence adopted in the 1954 Agreement on the Tibet Region of China and India.

Second, the Bandung final communiqué declared its full support of fundamental human rights, including the right of self-determination, respect for which was described as a pre-requisite for the enjoyment of all other human rights. The Ten Bandung Principles proclaimed the inviolability of sovereignty and the equality of all nations, large and small. But the Ten Principles also called for the development of peaceful co-existence among nations on the basis of ‘respect for justice and international obligations’. The Conference condemned extreme racism and applauded the ‘courageous stand taken by victims of racial discrimination, especially by the peoples of African and Indian and Pakistani origin in South Africa’. At first blush, then, we seem to have a contradiction. If Asian and African countries were to collectively support the struggle against apartheid, wouldn’t this be precisely a violation of the principles of non-intervention and sovereign equality that they held so dear?

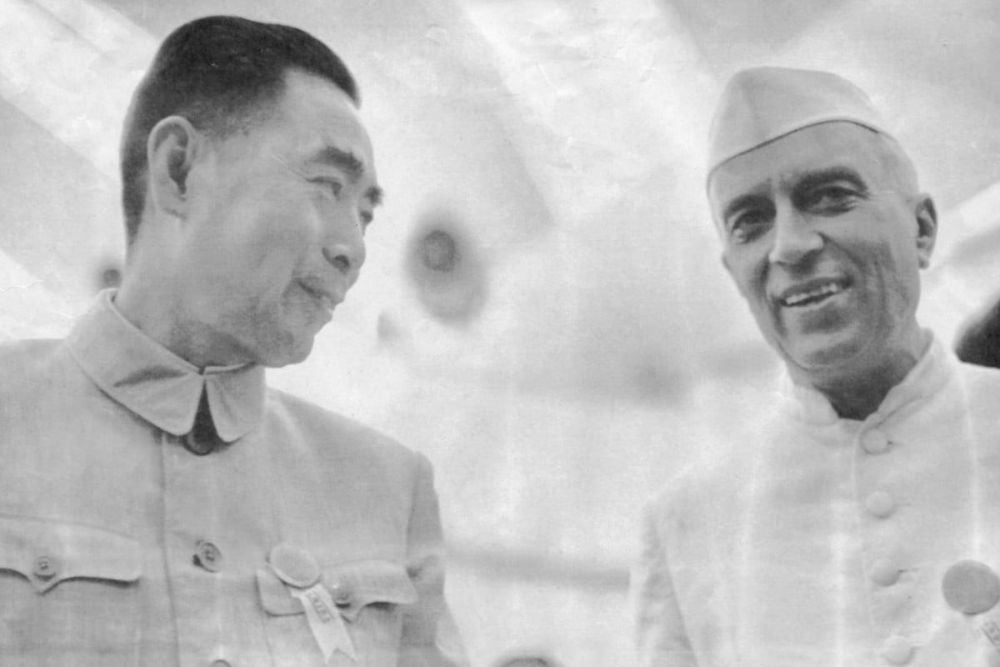

Zhou Enlai of China and Jawaharlal Nehru of India at Bandung, 1955. Photo Credits: UPI.

Zhou Enlai of China and Jawaharlal Nehru of India at Bandung, 1955. Photo Credits: UPI.

The issue was prevalent in what British IR theorist Martin Wight once called the ‘Bandung UN’: a historical UN General Assembly that sought to hasten the liquidation of empire and international-racial hierarchy. The ‘Bandung powers’ applied various forms of international pressure against South Africa, including through censure and resolution-making as well as diplomatic and economic sanctions (eventually, in 1963, the UN Security Council also adopted sanctions against apartheid, with its arms embargo being made mandatory in 1977). South Africa often alleged such actions to constitute ‘intervention’ in its essentially domestic affairs and that the Bandung states were therefore breaching Article 2 (7) of the UN Charter. Such an argument, also articulated in the 1950s and 60s by Pretoria’s Cold War allies, was so regularly deployed in the UN that it came to be described by Chile as ‘a little veto’ that stood in the way of liberation from lingering colonial bondage.

In and through the UN, international efforts against apartheid were solidarist with respect, for instance, to the enforcement of the law. But none---and this is the third step---were to be considered ‘intervention’ . And none were to be seen as contravening Article 2 (7). From the view of Bandung, the difference between internationalism and interventionism could be explained by the progressive development of norms and rules and a proper understanding of domestic jurisdiction as a concept based on law, not simply on geography. The legitimate solidarity of states to prevent atrocious crimes—to prevent genocide, war crimes, apartheid, and other crimes against humanity—was not considered intervention or interference in ‘essentially domestic affairs’ on account of the ways in which these large-scale abuses had become so widely known and institutionalised as shared international responsibilities. And while some sought to extend the Global South’s solidarist internationalism into a veritable proletarian internationalism, or into a liberal internationalism akin to the Reagan-Kirkpatrick Doctrine, these interpretations were deemed subversive by a historical Non-Aligned Movement that insisted upon independence rather than a side in meta-ideological conflict.

Rather it is to be understood that the deprivation of nations and peoples of their right to self-determination is precisely a violation of non-intervention. Legitimate solidarity is never to be mistaken for the sin of intervention.

And while, true, there of course did emerge in the 20th century glaring examples in which flagrant and large-scale breaches of human rights stirred little if any criticism in the UN—or in Southern forums such as the OAU—it does not follow that an absolutist conception of sovereignty was an expression of solidarist internationalism or a historical feature of the non-aligned vision of anti-hierarchical global order. It rather follows that Charter provisions regarding non-intervention, including OAU Charter provisions, were being shamefully misconstrued. They were interpreted out of context. To invoke the principle of non-intervention to shield the commission of mass atrocities would, in short, be just as empty a moral gesture and just as much an abuse as the ‘little veto’ of Article 2 (7) as historically invoked to suppress the UN-based anti-colonial and anti-racist movement.

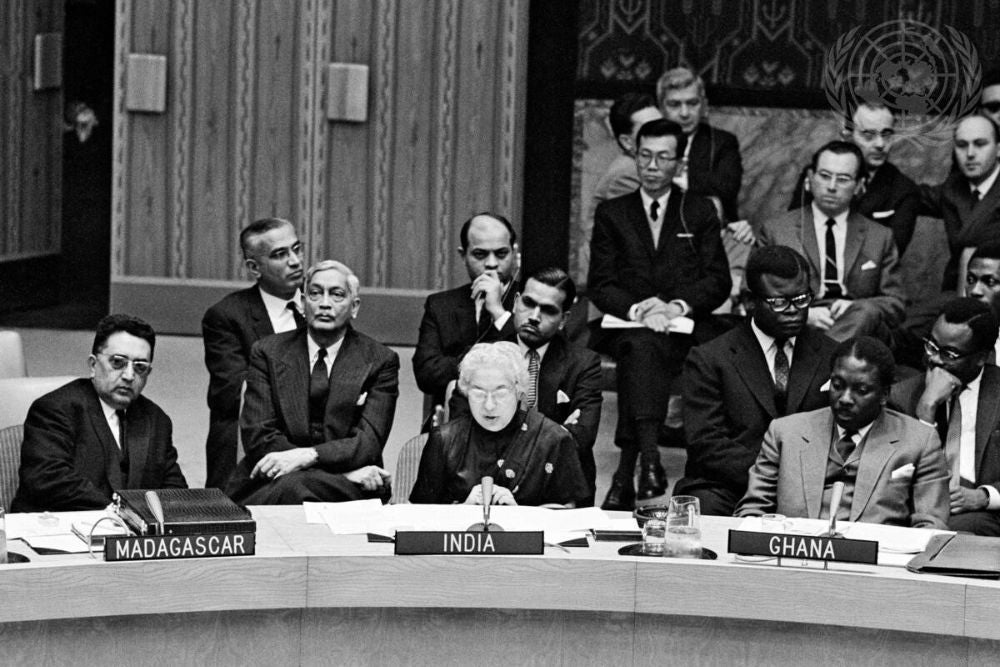

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (India) addresses the UN Security Council during its debate on apartheid, New York, 1963. Photo credits: United Nations.

Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (India) addresses the UN Security Council during its debate on apartheid, New York, 1963. Photo credits: United Nations.

Hence if Martin Wight got the phrase ‘Bandung UN’ very right, he also got something very wrong. When he claimed that the ‘limits [emphasis mine] of Article 2, Paragraph 7, were first explored in the case of South Africa,’ and that ‘it was not contemplated at San Francisco that the UN should be an organization for collective intervention’, he also misunderstood the Bandung theory of what it means to intervene. And it is on account of a similar misunderstanding that it is today so commonplace to detect in the solidarist internationalism of the Global South a contradiction with its non-interventionism. For non-intervention need not imply non-involvement or indifference. And, like non-alignment itself, it should not be misconstrued as an amoral concept. Against the background of Bandung, we can see the function of non-intervention very differently: as a shield against colonialism and foreign control, and even a ‘mighty sword’ in the language of politics and its function in the legitimation of social action.

Speaking in the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of parliament, five months after Bandung, Jawaharlal Nehru portrayed ‘non-interference of any kind’ as an Asian value ‘as old as our thought and culture’ and a defining trait of Asian civilizations. It is pertinent, especially now, in an era of a rising Asia and increasingly multipolar world, to recover and compare multiple interpretations of this core vocabulary of International Relations. Intervention before Interventionism, published with Oxford University Press (2024) and revised during my time as a Postdoctoral Fellow at ARI, traces the normative descent of such plural and contested meanings in the global society of states. It provides a repertoire of the intervention concept’s myriad possibilities for a turbulent present.

Patrick Quinton-Brown is an Assistant Professor of International Relations at Singapore Management University (SMU). From January 2021 to October 2022, Patrick was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore.

Patrick's current research focuses on the intergovernmental practices of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, particularly in relation to sovereignty and non-intervention and is the author of Intervention before Interventionism: A Global Genealogy published with Oxford University Press in 2024.