Writing ‘Islam and Asia: A History’

https://doi.org/10.25542/ydhq-0bq1

In August 2017, I landed in Singapore with my family, and probably more luggage anyone should be allowed to carry on a plane. Alongside my partner, a 10-month-old, and more family to help with the baby, I also had with me plenty of hope, energy (as much as a new mom can have), and ideas to finally get serious about writing an overdue book about ‘Islam in Asia‘ (Islam and Asia: A History, Cambridge University Press, 2020).

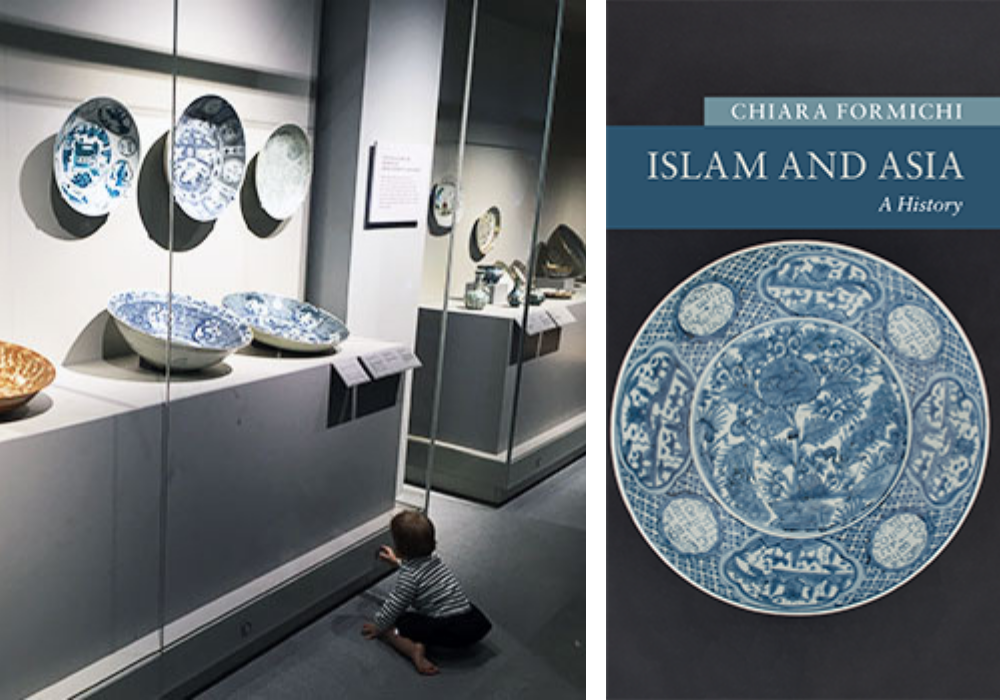

After a few weeks sitting in my office in the brand-new AS8, I visited the Asian Civilisations Museum. This had always been one of my favourites in town, and I was eager to see the renovated galleries. Walking through the Trade galleries, with baby in tow, the porcelain collection provided me with the visualisation of what I was trying to get on the page. Traders, craftsmen, objects, aesthetic models; these had all circulated between the Mediterranean and the Pacific for centuries (millennia, in fact), inspiring one another, adapting to and reflecting, prevailing cultural trends.

The blue-and-white plate shown on the cover of Islam and Asia is the ultimate representation of this idea. Decorated with birds, flowers and pagodas, this specific plate was produced in China. But the Islamic profession of faith inscribed in the medallions is a clear sign that it was made for a Muslim audience, likely either in Southeast Asia or West Asia. The blue pigment, sourced from Anatolia and Iran and known in China as hui-hui qing (‘Muslim blue’) because of its connection to Muslim networks, eventually became a hallmark of Chinese imperial porcelain during the Ming dynasty. Chinoiseries porcelain appeared all over Europe, and ‘Muslim blue’ plates and vases came to represent 17th century aesthetics well beyond the Islamic sphere.

Islam and Asia: A history

The big idea behind Islam and Asia is to present a portrait of Asia as a cohesive space of Islamised interaction, in which Asia is central to the history of Islam. Asia’s Muslims played a key role in shaping Islamic exegesis, and Islam played a role in shaping Asia as we know it. This approach rejects the dichotomous narrative of ‘centres’ and ‘peripheries.’ There is a generally accepted assumption, especially among scholars of Islam, that religious practices in West Asia, and Arabia especially, are a golden standard of orthodoxy (or orthopraxy), and the most authentic and the purest.

There is a generally accepted assumption, especially among scholars of Islam, that religious practices in West Asia, and Arabia especially, are a golden standard of orthodoxy (or orthopraxy), and the most authentic and the purest.

Practices in Asia (as well as the Americas and Africa) are derivative, if not deviationist, when they are not mirror images of ‘Arab’ practices (in which case, incidentally, they are tantamount to fundamentalism and potentially terrorism).

I argue instead that Islamic practices everywhere have emerged from conversations and exchanges between ‘Islamic’ and ‘local’ phenomena. Reflecting on how pre-Islamic and Islamic ideas, rituals, laws, and ways of life affected each other, I advance the idea that orthodoxy and orthopraxy are chronologically and geographically contextual. This was largely the outcome of ongoing Intra-Asian connections that linked the Mediterranean to the Pacific through scholars, goods, political ideas and aesthetic ideals. Muslims from/in the so-called ‘peripheries’ exerted influences onto those at ‘the centre,’ and elements of Islamic culture informed the shaping of Asia more generally.

The chapters move forward in a chronological order, with each temporal bracket narrated following a defining theme. Starting off with the emergence of an Islamic society in Arabia, and the movement of Muslims outward from the Arabian Peninsula all the way to Southeast Asia and China, the chapters then reach into the contemporary era, with the lion’s share of the book focusing on the 17th to 20th centuries.

Recurrent themes, interwoven in the narrative, include: the position of women as political and religious leaders; reflections on how specific elements of material culture can illustrate conversations on orthodoxy/orthopraxy and Islamisation; the position of religious minorities; and the impact of colonial and neo-imperialist projects on how we approach the study of Asia and Islam.

Writing and thinking from Southeast Asia

The fellowship at ARI is what enabled me to spend time thinking, conceptualising, structuring and drafting the core chapters of Islam and Asia. The shelves in my office quickly filled up with tens of books about Islam in Central Asia, the Soviet Republics, India, China and, of course, Southeast Asia. Art history, archaeology and numismatics mixed with history, politics and anthropology. I was amazed, often surprised, by what NUS library had to offer, and so I dived into new readings.

But Singapore is not just rich in resources, what makes it special is its people. The same is true of ARI where chance encounters in hallways, canteens and shuttle buses inevitably turn into stimulating conversations. I could think of no better place to work on a book that spanned so broadly across ‘Asia,’ and focused on Intra-Asian connections.

I think I first heard the expression ‘Intra-Asian Connections’ at ARI, as a postdoctoral fellow in the Religion and Globalisation Cluster. Beyond the jargon and theories, Singapore, located on the Strait of Malacca, is symbolically an ideal location to pursue this work: early Arab and South Asian Muslim traders passed through it as early as in the 9th century bringing Islam to Southeast Asia; today, ships from Malaysia carry halal shipments to China. Southeast Asia remains the furthest point from Mecca with a sizeable Muslim population, so significant in fact that 25 per cent of the world’s Muslims reside here.

The most exhilarating part of the research was to look for those hidden Muslim figures who were influential in shaping Islamic thought. Many of them were in fact from Southeast Asia. It was this process that has allowed me, maybe a little surreptitiously, to conclude the book with a chapter that presents Indonesia and Malaysia as primary settings for a continued process of de-centralisation of religious authority.

As Abu ‘Abd Allah Mas’ud ‘al-Jawi’ had been a revered scholar living in Mecca in the early to mid-13th century with stated (although unspecified) connections to Southeast Asia, so were the many Islamic female scholars who gathered in rural Java for the 2017 Indonesian Conference of Women ‘Ulama (KUPI); and the Malaysian organization, Musawah, that brings together feminist scholars of Islam worldwide.

In a different realm, Malaysia has also emerged as a global force in halal certification and handling, with ties to China as well as European markets. Southeast Asian Muslims are trailblazers in shaping Islamic culture globally.

The most fundamental of inspirations for this book came from my teaching. Not only did I use lecture notes and hand-outs compiled during a decade of teaching courses on Islam in Asia, but even more excitingly, I must confess, I also used sources that students brought to my attention in discussions and assignments.

I see this writing project as a manifestation of the virtuous cycle of teaching, where knowledge is generated for students, but also by students, and not as an end in itself, but to be recirculated and re-used. This is why I dedicated this book to my students.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.