The labour emigrants and the labour exporting nation in Covid-19 times

Exequiel Cabanda, 30 Oct 2020

Photo: © Jay Rommel Labra

Imagine the seafarers on board cargo vessels, oil tankers or cruise ships who are stranded at seas or seaports and unable to return home? How about nurses who have their work visas approved, their luggage packed and ready to fly to Singapore, but could not leave? Border closures, travel bans, and retrenchments are few of the widely used jargons in these Covid-19 times. Indeed, the Covid-19 pandemic has made the world in motion stop!

In a webinar hosted by the Asia Research Institute entitled ‘Deferred Departures, Unhappy Returns: Pandemic and the Labour Exporting Nation’, Assistant Professor Yasmin Ortiga and Ms. Karen Anne Liao shared the findings of their project that examines the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic to labour exporting countries like the Philippines. This essay presents their key findings and attempts to contextualise these findings in the broader aspect of migration studies.

As a migration scholar, my work focuses on migrant-sending countries. I have always been interested on how migrant-sending countries manage and facilitate labour export, what are the effects to labour migrants and their families left behind and how labour migration impacts communities and countries. Put simply, I am interested in the migration-development nexus, especially on the role the sending countries’ government in managing labour migration.

Like me, most of the scholars that examine migrant-sending countries centre on the deployment part of the migration process. This is not the case for the research of Asst. Prof. Ortiga and Ms. Liao, which targets both the deployment and the repatriation of labour migrants. More so, they added a fresh dimension by putting the Covid-19 pandemic in the equation. The result is a renewed look at the migration process through the story of skills: the deferred departures and unhappy returns of labour migrants. Conversely, their work offers two dimensions on how the Covid-19 pandemic impacts the labour export-system– (a) deployment or the ‘sending’ of migrant workers abroad; (b) repatriation or the ‘return’ of migrant labour to their home country using the case of the Philippines.

The Philippines as a leading source of migrant workers

The Philippines is a primary source of labour migrants in the world such as domestic helpers, entertainers, engineers, seafarers and nurses, among others. The country has a very explicit state-led labour export policy, which began as early as the 1970s. Initially, this policy was a short-term solution to the rising unemployment and foreign exchange problems that the country has experienced during the period.

Over the years, this labour export policy has evolved as a long-term solution. Policymakers in the Philippines have considered the positive impacts of remittances on economic growth. Historical data reveals that migrant’s remittances have a 10 per cent share in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Likewise, the Philippines is the third largest recipient of remittances in the world, which is equivalent to $US 33 billion annually.

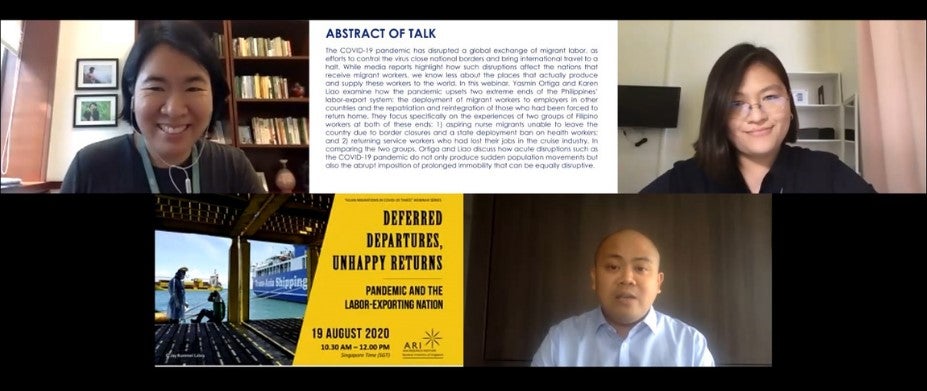

‘Deferred Departures, Unhappy Returns.’ From top left to bottom: Yasmin Ortiga, Karen Liao and Exequiel Cabanda during their Asia Research Institute presentation

Deferred departures: the case of nurses

For Deferred Departures, Asst. Prof. Ortiga discussed the complexities of the “deployment ban” of health workers that include Filipino nurses who are about to leave for their overseas jobs. The deployment ban was stipulated in the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) Governing Board Resolution No. 09 issued on 2 April 2020.

The ‘deployment ban’ aims to channel Filipino nurses to local hospitals to care for the Covid-19 patients. This policy covers all aspiring migrant nurses who have signed overseas employment contracts and approved visas.

However, the policy has been amended on 13 April 2020 to allow those nurses who have signed employment contracts as of 8 March 2020. As of this writing, the government has further eased the policy restrictions by allowing nurses with ‘complete documentation’ to leave the country to work abroad.

There are two categories of those nurses who were affected by the deployment ban. The first category is the ‘defiant’ nurses. They are nurses who did not respond to the call of the government to work in local hospitals. These nurses prefer to wait until the deployment ban is lifted. As a source of income, they temporarily engaged in home-based entrepreneurial venture like online selling. The second category is the Department of Health (DOH) nurses. They are nurses who have answered the call and work in local hospitals. Some of these nurses are likely to have no hospital experience. These nurses have used the mass hiring of nurses as an opportunity to accumulate skill.

As a result, those nurses who have hospital experience are less likely to take on hospital jobs during this pandemic. For those nurses who are willing to work in local hospitals, they are likely to have no hospital experience.

Unhappy returns: the case of seafarers

For Unhappy Returns, Ms. Liao explained the anxiety and distress of returning seafarers or service workers who are working in the cruise line industry. These seafarers while on board the ships have experienced multiple anxieties. These are uncertainties of future jobs and the problem on how they can go back home considering port closures and massive flight cancellations.

For those seafarers who have been repatriated back to the Philippines, the struggles and anxieties have continued. Ms. Liao discussed the distress they have experienced in quarantine facilities. These seafarers have faced significant delays in Covid-19 testing, waiting period for results, the lack of transportation and flight cancellations on their way to their hometowns.

Moreover, these seafarers fear the loss of income and prolonged immobility due to the pandemic.

In terms of policy, the Philippines have a system in place for the repatriation of Filipino workers. However, the government is not ready for the massive influx of returnees. The concerned government agencies have struggled to build quarantine facilities, organise Covid-19 testing and support reintegration in local communities.

Implications to migration studies

In a broader sense, the findings of Asst. Prof. Ortiga and Ms. Liao have given us a fresh perspective on how to look at countries that are known to produce and promote international labour migration. That is, in the time of pandemic, a labour exporting nation is likewise caught in a period of anxiety and distress.

As for the Philippines, it has been forced to set aside its profit-seeking behaviour in lieu of a national health emergency. However, it has been unsuccessful in maximising its health manpower who are mostly unwilling to take up local hospital jobs.

Currently, the country is also overburdened by returning labour migrants who cannot find themselves a place in the local job market. More so, the story of skills of these two types of migrant workers during the pandemic highlights the ‘wastage’ of skills both from aspiring nurse migrants and returning seafarers.

Dr Exequiel Cabanda is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University or Singapore. He obtained his PhD in Public Policy and Global Affairs (March 2019) at the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His PhD thesis has examined the different roles of a sending state in managing the emigration of nurses using the public policy and negotiation frameworks.

Dr Exequiel Cabanda is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University or Singapore. He obtained his PhD in Public Policy and Global Affairs (March 2019) at the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. His PhD thesis has examined the different roles of a sending state in managing the emigration of nurses using the public policy and negotiation frameworks.

Dr Cabanda’s most recent journal article, 'We Want Your Nurses! Negotiating Labor Agreements in Recruiting Filipino Nurses' was published in Asian Politics & Policy (July 2020).

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.