Performing “Lives”: Protestant churches’ worship and fellowship during COVID-19 lockdowns

contributed by Junesse Crisostomo, 29 September 2021

When the Philippine government placed provinces and cities under Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ), schools and universities were suspended, mass gatherings were prohibited, businesses were closed, and mass transportation became restricted. Religious practices which are usually performed in the presence of a community of believers had to be suspended as well, forcing churches to transport their activities to online settings.

As a member of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), I have an insider perspective on how three of our local Protestant churches performed religious practices and fellowship in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recordings of live-streamed Sunday services and Bible studies are easily available online, allowing me to have a memorable autoethnographic “church-hopping” experience. While sitting in the confines of my study area at home, I can be in three churches at once.

The church on the frontlines: Making sense of the liminal period together

A government-imposed lockdown is an example of a liminal period experienced by citizens together. Coming from the word “limen”, liminality is a kind of threshold, a time-place where ordinary life is suspended and rituals break free from rigidity through the embracing of ingenuity and creative expression. In the case of the three churches I observed, this liminal period had to be rhetorically justified in order for the members to accept that their cherished religious rituals and traditions will be transported to an online setting. In my interviews, the lockdown was perceived as a necessary phase that encourages God’s people to purify themselves from material obsessions and greed, bringing them back to the pure elements of familial bond and spiritual focus. Most importantly, my interviewees construct the pandemic as a spiritual rite of passage of “returning to the Lord”, strengthening one’s faith, and repenting for one’s sins. That said, special actions that need to be performed in this liminal period include praying and involving oneself in religious activities. From this perspective, the pathological and socio-political drama of the COVID-19 pandemic takes on a sacralized meaning. To Protestant Christians, the pandemic is not just a global health crisis, it is also a sacred rite of passage toward spiritual salvation and transformation.

The church online: Communion and community

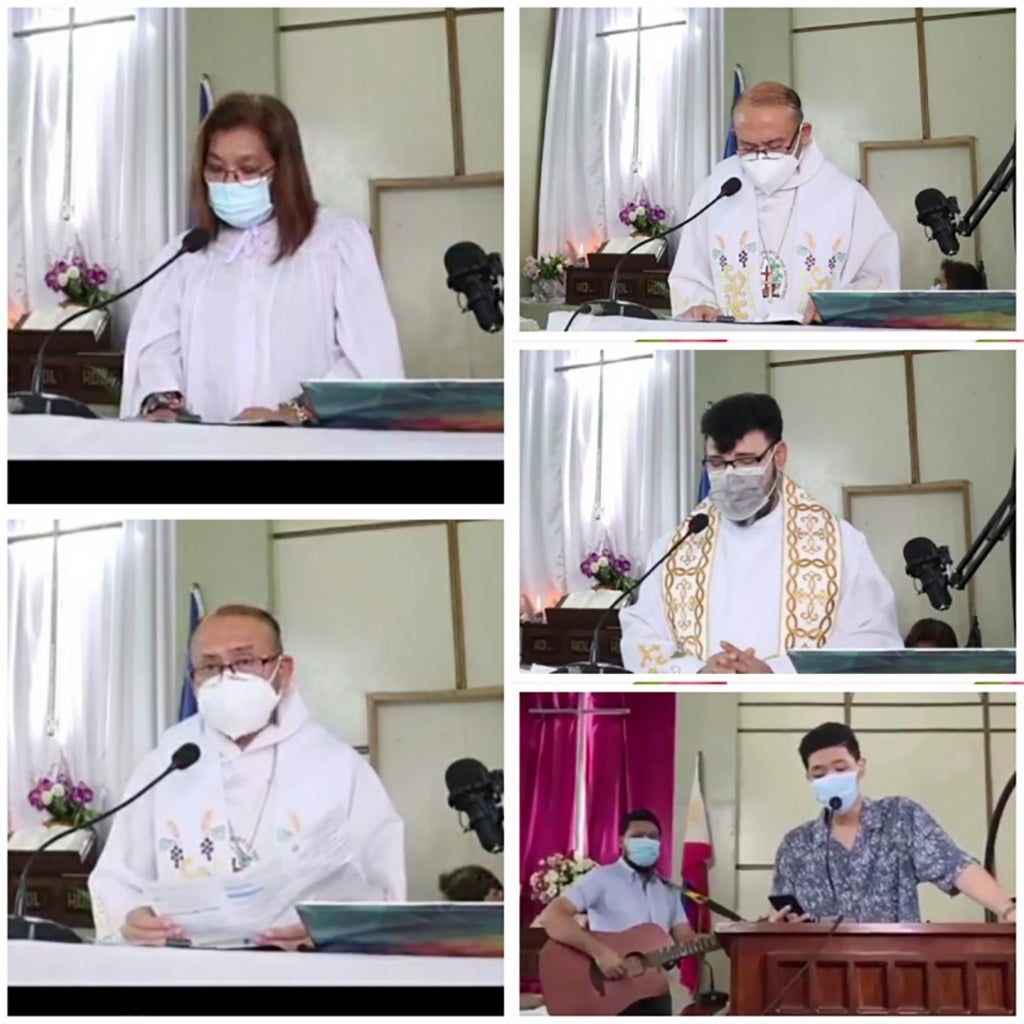

During the online church service, the pastoral team is seen in their religious robes but with the addition of protective gear. The members of the team also manifest feelings of communitas, or inspired fellowship, which is usually experienced by a group of persons collectively experiencing a liminal period. They report new feelings of positivity, solidarity, and bonding. Since they are the ones performing the rituals physically in church, they cast God, the supernatural, in their narratives as a co-performer during these activities, giving them divine protection from the virus.

Figure 1. UCCP Malolos Evangelical Church’s worship team, 2021 (image courtesy of Hazel Esguerra, church member)

On the side of the audiences, most families share one device for livestreaming, prompting them to designate a space in their house as a communal place of worship every Sunday. The notion of sacred time is also practiced by consciously retreating from the demands from one’s immediate environment as they prepare for church activities. According to one interviewee, “Before prayer meetings and Sunday worship, we make sure that we are rested first. At home, there are lot of things going on—cooking, taking care of the kids and senior citizens—there are so many distractions”. Indeed, through online videoconferencing platforms like Facebook messenger, the sacred enters domestic spaces and the mundane meets holy ground. By attending church and turning on one’s camera, we welcome others into our homes and they in return welcome us. In this setup, we perform our lives as we perform “live”.

Figure 2. Members of UCCP San Simon attending mass through Facebook messenger room during Easter service, 2021 (screenshot mine)

Figure 3. Members of UCCP San Simon attending church service through Facebook messenger room, 2021 (screenshot mine)

There is also anticipation in partaking in these rituals as explained by one member- “we assemble at the same time and we are excited to see who else are joining and coming. We are joyful because many people join the activities to pray and listen. We are together”. This awareness of one’s embodied real-time participation encourages expression and inclusion. In this way, one does not simply watch the livestreaming of the mass, one participates in the mass. One notable church activity that emphasizes the importance of embodiment and participation is the virtual choir performances in services and church celebrations. A choir member undergoes the process of learning the song through repetitive practice. The choir members also don costumes of the same color to indicate harmony and togetherness. The person prepares a space at home conducive for the recording of one’s piece and performs with a consciousness of an audience in mind. Watching the final virtual choir presentation during church service truly boosts a community’s sense of “we are all in this together.” Bodies separated by distance are edited to be singing close together, voices recorded asynchronously find temporal harmony, and feelings of isolation are overpowered by the hype and hope of reunion.

Figure 4. UCCP Church of the Evangel Virtual Choir, 2021 (screenshot mine)

Church members also have an active participation in online activities through rhetorical performances as the pulpit is shared with laypeople. When a strict lockdown was implemented in Luzon during Lent 2021, lay people were assigned to deliver homilies for Christ’s Seven Last Words on the Cross. They were required to record their speeches and send it to the technical team for editing before livestreaming. Speakers were able to deliver their messages with the backdrop of their home office, their bedrooms, their salas, and with makeshift wooden crosses behind them. According to one interviewee who delivered one of the sermons for the Seven Last Words activity, “While filming the sermon on my own, I felt a bit conscious and shy talking in front of the video. But during the livestream, we all felt excitement seeing the final product. Each speaker had their own style and backdrop. There is a different kind of excitement and sense of community.” Truly, inspired fellowship is felt when we embody these rituals in our private spaces while conscious of the presence of other bodies “out there” performing the same acts with us.

Figure 5. Seven Last Day Speakers, UCCP San Simon Lenten Worship, 2021 (image courtesy of Lorna Dagdag, church member)

Another important ritual that is now performed at the confines of one’s home is the Holy Communion. In pre-pandemic settings, the pastor presents the elements (the bread and wine) to be followed by participants approaching the altar in batches to kneel down and partake of the body of Christ. There was a sense of structure and solemn rigidity to the act. However, now that the Holy Communion was moved online, what is experienced is creative solemnity at home. According to one interview, “the communion is creative. One finds available elements at home to use. We bless the orange juice and the biscuit. It is really a joyful experience that we can still do the communion”.

Figure 6. UCCP San Simon Members partaking in The Holy Communion, 2021 (screenshot mine)

Interestingly, this sense of belonging to a community of faith is sustained even after livestreamed recording are finished. Facebook messenger group chats act as a way for members to stay in touch, share prayer requests, discuss about random topics, and plan for projects such as feeding programs for the community. This is what Auslander terms as “online liveness,” a group’s sense of continuous connectedness with others through the affordances of online communication platforms.

The church on the line: concluding reflections

The virtual setup of church activities poses opportunities and challenges for churches. One of the most notable opportunities I observed is the effectiveness of virtual activities in sustaining community within the church. Church members noted that through online rituals and activities, members who have long been inactive, those who have already migrated abroad, and even relatives of regular church attendees started to actively participate in church activities. Because activities are now livestreamed or pre-recorded, the engagement of members has increased. For the bigger and more financially-stable churches, this virtual engagement also translated into the financial aspects of church ministry. There was a considerable increase in donation of tithes and pledges as well as gadgets that need to be used for livestreaming. The church also became more capable to extend humanitarian help to the needy because of the participation and donations of its members.

However, challenges are more apparent in the situation of small and poor churches. Since the pastors and the members do not have access to the internet, virtual participation in activities is hindered. These churches also became more financially-challenged as a result of this pandemic. Additionally, their pastors are also more exposed to vulnerable situations because they have to pray for their members in person and conduct the Holy Communion through house-to-house setups. This shows us that the ability to smoothly transition our worship practices to the online setting is also a product of the socio-economic status of a church and its members.

To conclude, online church activities produced communitas through members’ embodied participation and creative expressions of faith, legitimizing the spiritual dimensions of the pandemic’s liminal qualities. In the intersection of sacred time-spaces with the domestic and the mundane, members witnessed live performances of performing “lives”, boosting the morale of the faith community through identification and inspired fellowship during a time of crisis and isolation.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Junesse Crisostomo is a faculty member at the Department of Speech Communication and Theater Arts at the University of the Philippines Diliman. She finished her MA Communication degree from the same university and studied the organizational rhetoric of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) on human rights during President Duterte’s administration for her master’s thesis. Ms. Crisostomo has presented her research in various conferences in the Philippines and abroad, and has published her works in Humanities Diliman and Plaridel. Her research interests are in rhetoric, religion, and performance.

Other Interesting Topics

To Go or Not to Go? Mazu’s Annual Procession in Taiwan amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic

In the first half of 2020, the whole world was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. As strict border controls were timely imposed, disruption to the daily lives of the Taiwanese was less severe. Chinese folk temples in Taiwan also implemented anti-COVID measures such as taking temperatures of visitors and ensuring social distancing. The four-day long holiday...

Conflicting narratives of Covid-19 in Brazil: How religion influences spatial behaviours in Belo Horizonte

Religious identities are important factors influencing human behaviours in urban spaces. Using insights about the relationship between religion (Islam) and conceptualisation of public space as well as the relationship between social interactions and infrastructure from studies one author has conducted in Malaysia...

The Cult of Goddess Pattini at a time of Pandemic: Gammaduwa as a Strategy of Supernatural Protection

During times of uncertainty and danger, people often use rituals to reduce their stress and exert control over their environment. A global pandemic is also a time of significant transition and uncertainty when people have greater need for physical and social support. Over the past year, people have used their ritual traditions as a strategy of invoking supernatural power...