Digitalized Buddhist Ritual Practices in Sri Lanka during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic

contributed by Premakumara de Silva, 5 May 2025

The twenty-first century has seen the dawn of the digital age. An ever-increasing percentage of people receive and use their information in digital form, through the internet. In this context, I am interested in documenting new forms of Buddhist religious responses, ritual innovations, and power dynamics in Sri Lanka during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. How is the mutual shaping of religion and society unfolding during and after a pandemic in the context of a highly digitalized world?

During the pandemic, local understandings of disease and misfortune played a crucial role in combating the coronavirus alongside biomedical treatments. In times of uncertainty and danger, people often use rituals to reduce their stress and exert control over their environment. A global pandemic is also a time of significant transition and uncertainty where people have a greater need for physical and social support.

In Sri Lanka, there is a rich repertoire of magical actions and ritual resources that can be invoked to bring about protection (araksava) against misfortune and illness. The Buddhist concept of karma motivates much of the Sinhala Buddhist attitude to illness and misfortune, and is implicit in many aspects of everyday life. In theory, no one can have an entirely good karma, hence anyone can be afflicted with misfortune and illness by supernatural beings. Thus, the immediate cause of all illness and misfortune may be physiological or due to the action of external spirits. The ultimate cause is simply the bad karma of the person or groups concerned. One of the major goals of the protective (araksaka) rituals of the Sinhala Buddhists is the cure, control, or extirpation of individual and communal misfortune and illness caused by supernatural beings such as gods, planetary deities, yaksa, preta (ghostly beings) and even human. Generally, those protective rituals operate at the level of individuals (tovil/ shanti karma), and communities (gammaduwa/kohomba kankariya) (see de Silva). The pandemic posed a challenge to these traditional methods because it restricts the possibility of collective/communal action in the face of misfortune. It also presents particular challenges to Sinhala Buddhist conceptions of ritual as well. The question is: how did Sinhala Buddhists deal with the new threat and its aftermath?

During the pandemic, Sinhala Buddhists tended to use their protective ritual traditions as a strategy for invoking supernatural powers to control the spread of COVID-19. I have shown how such ritual practices in 2020 managed to move quickly, out of necessity, to an online and/or hybrid mode of delivery (see de Silva 2021).

Use of Traditional Buddhist Rituals in the Digitalized Mode

During the pandemic period, restrictions on social gatherings greatly impacted religious life. Hence, performing a ritual had to comply with the government rules in relation to COVID-19 lockdowns and curfews. While Buddhists sometimes face challenges in conducting long-anticipated rituals even under normal circumstances, such as being unable to perform a promised collective ritual like gammaduwa, during the pandemic all practitioners were affected simultaneously, bringing about emotional responses of shock, fear, and uncertainty. At a time of crisis, when performing rituals seems more important than ever before, practitioners need to shift their ways of conducting rituals either to the home or to virtual/online spheres. In such a context, live-streamed worshiping, chanting, blessings and performances have become important means through which priests and ritual performers can stay in touch with devotees (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Screenshot of young Buddhist monks invoking ritual blessings, telecast by the private TV channel Derana, 4 May 2021.

Apart from the invoking sonic power of Buddhist sutta chanting in Sri Lanka, there is a system of beliefs for invoking ritual protection for the spread of infectious diseases that locals refer to as deiyange leda, or “diseases of the gods.” Like COVID-19, most are viral diseases: chickenpox, measles, mumps and smallpox. In general, they are also referred to as deviyanne dosa (dosa or misfortune caused by gods): and under this classification fall subtypes of dosa, all caused by the wrath of the gods (deviyo) of the Sinhala Buddhist pantheon. According to Obeyesekere, the Sinhala people use dosa in its etymological meaning of “faults” or, to be more exact, “misfortune”. The term dosa for misfortune is probably the most common term used in Sinhalese rituals (Obeyesekere 1985: 44-49). Among those gods who cause dosa, Vishnu, Saman, Kataragama, Pattini, Kali and Suniyam are the most popular, in contemporary Sri Lanka. The first four gods are regarded as the guardians of Sri Lanka and more benevolent figures, in comparison to the punitive deities Kali and Suniyam.

Rituals like gammaduwa and kohomba kankariya (see figures 2, 3, 4 & 5) were performed to honor these deities and seek blessings to overcome dosa caused by them, particularly addressing the goddess Pattini. Such traditional rituals called shanthi karma, or rituals of solace, are a combination of dance, chanting, offering and the beating of drums to invoke blessings of deities and eliminate evil spirits (see figure 6). There are many such rituals in Sri Lanka; some of them are region-specific, but overall performed with the purpose of warding off diseases and protecting the community (see Kapferer 1983; Obeyesekere 1985; Scott 1994; Simpson 1997, 2004; de Silva 2000; Reed 2010; Amunugama 2021).

The gammaduwa, also known as devol madu shanthikarmaya, is a ritual tradition that invokes the blessings of the goddess Pattini. Gammaduwa means "a hall in the village", constructed to worship gods by the people of one or more villages. Traditionally, it is practiced predominantly in the low country, performed by a kapurala (priest, spiritual leader and healer) to ensure the well-being of the village and a plentiful harvest. The gammaduwa comprises offerings of plants (betel leaves and festival boughs) and lights, planting the torch of time, performing fire trampling rituals and ceremonial dances for the participating gods. Through these acts, Pattini's status as Mother Goddess is reaffirmed (Obeyesekere 1984).

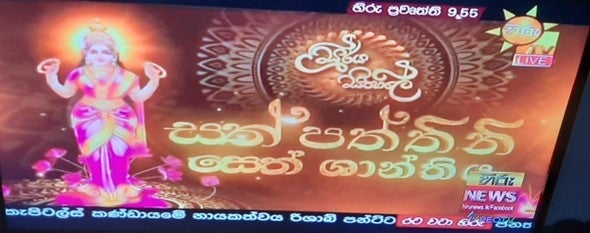

Figure 2: Screenshot of the goddess Pattini escorted for ritual blessing. Telecast by the private channel Meth TV, 21 September 2021.

Figure 3: Screenshot of a New Year blessing-evoking ceremony for the goddess Pattini. Organized and telecast by the private TV channel Hiru, 31 March 2021.

Figure 4: Screenshot of a live telecast of gammaduwa performed at the central shrine of the goddess Pattini by the state-owned TV channel, 28 August 2021.

Figure 5: Kandyan Up Country dancing of kohomba kankariya, a communal blessing and protective ritual, 15 August 2021. Credit: Sunday Observer.

A point to be discussed is that today, a communal ritual like gammaduwa is performed not only in a physical manner in rural, urban and national contexts, but also on the digitalized platforms for capturing wider audiences. As I discussed elsewhere, during the Covid pandemic the only available way of bestowing divine protection to prevent the spread of the virus was to invoke rituals powers in a digitalized mode (de Silva 2000).

Although the authorities did not allow communal gatherings during the first viral outbreak, such a decision was gradually relaxed following the management of the second wave. According to media reports, there were several gammaduwas organized by different groups, including few media channels, to seek protection of Pattini to prevent the spread of the coronavirus (see de Silva 2021).

Figure 6: Screenshot of a demonstration of protective measures to be taken during the pandemic by using traditional mask dancing, 11 May 2020. Telecast by the private TV Channel Derana.

Another point I want to make here in this transformation is that the protective and healing capacities of the goddess that were enacted in gammaduwa on the village as a matter of the health of social/communal body, have extended now to heal the nation as a whole, against what has been perceived as a foreign threat like the COVID-19 pandemic.

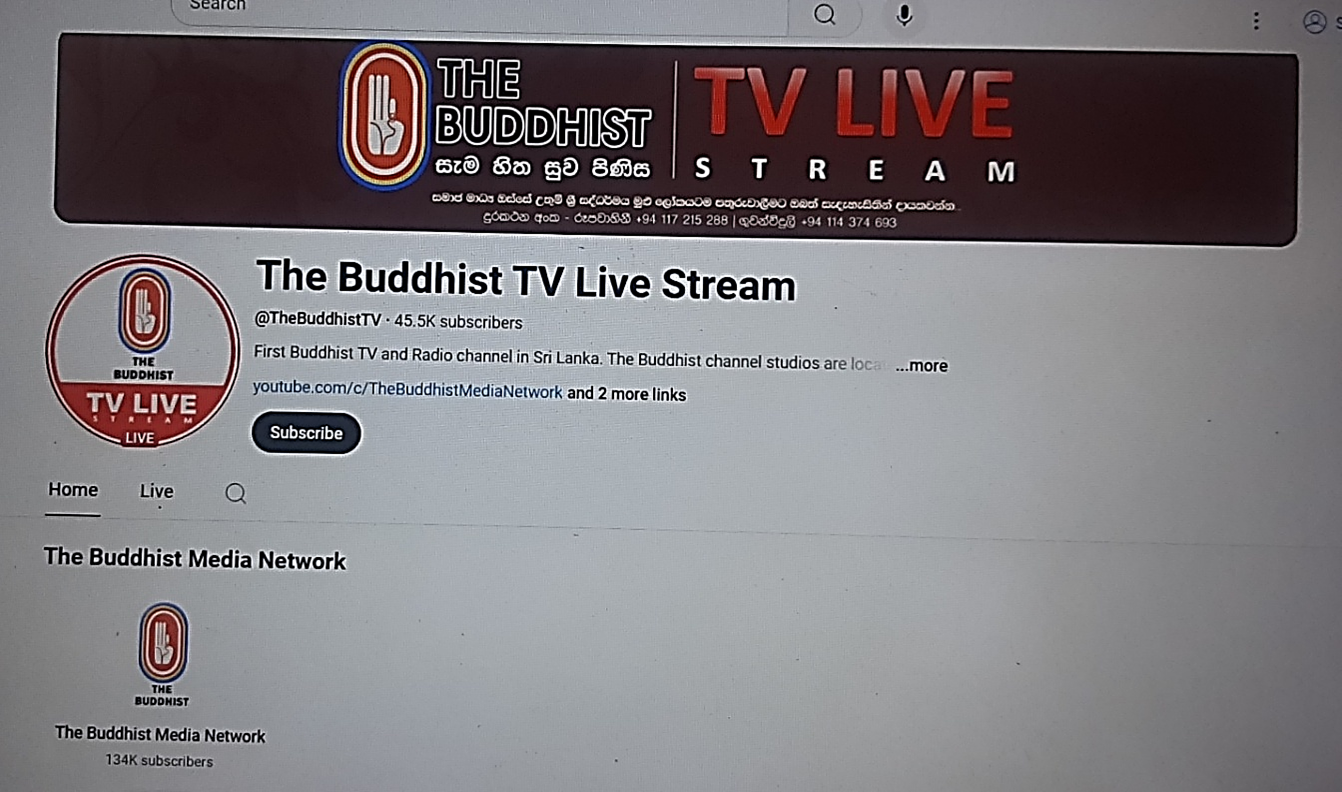

The striking feature of religious rituals including gammaduwa is their ability to change in response to the current pandemic situation. In the event of a marked absence of audience for the performance, it can reach out to larger audiences or participants via live-telecast of the event through new digital platforms, thereby creating virtual devotees. It is important to note here that the continuation of traditional ritual performances via live-telecast and posted telecast-recordings shared via social media including YouTube is quite evident in post-pandemic Sri Lanka. For example, see the YouTube link of a gammaduwa performance in 2023. It has 450 subscribers and 9.3k views to this date. Another example is this Buddhist Media Network (figure 7) with 134k subscribers, which is meant to be devoted to promote Buddhism and Buddhist rituals both locally and internationally. This proves to be a continuation of traditional Buddhist ritual practices which were visible from the pre-pandemic and pandemic to the post-pandemic context.

Figure 7: A screenshot of the Buddhist Media Network, 2 March 2025.

Figure 7: A screenshot of the Buddhist Media Network, 2 March 2025.

Conclusion

In the context of COVID-19, there have been strong sentiments in Sri Lanka that deploying ritual blessings by conducting special religious rituals such as pirith chanting and performing traditional deity rituals like gammaduwa, alongside the use of various traditional Ayurvedic medicines can counter the threat of the deadly coronavirus. Like many other social groups, Sri Lankan Buddhists were able to adapt various forms of religious responses, and ritual innovations during the global pandemic. While previous articles have analyzed how state regulations on rituals and covid protocols have marginalized religious minorities and fueled inter-religious tension (Gajaweera and Mahadev 2021), and how places of worship in Sri Lanka have served social purposes in times of crisis (de Silva 2021), this piece shows how people resort to the available religious and ritual traditions to seek divine protection from the virus. Rituals of protection did not exclude or contradict the vaccination program in place in the country.

During the pandemic, traditional Buddhist rituals performances like gammaduwa have swiftly moved to digital platforms as a safe mode of delivery of divine protection and blessings. Such digitalized forms of divine protection and blessings are still continuing as “pandemic leftovers”. This is partly because, during the pandemic the society became more digitally equipped and tech-savvy, particularly in the sphere of religion and rituals.

Clearly, such digitalized Buddhist practices have the potential to evolve over time as technology improves and develops, enhancing the experience of users even in post-covid Sri Lanka. The field of digital religion is important to understand dynamism and changes within the Buddhist religion. As a concluding remark, let me emphasize that digital religion is not just the phenomenon of online religious practice for spiritual purposes but rather the extension of traditional religion into a new culture due to the widespread digitalization of society.

References

Amunugama, Sarath 2021. Kohomba Kankariya: The Sociology of a Kandyan Ritual. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications.

De Silva, Premakumara, 2000. Globalization and the Transformation of Planetary Rituals in Southern Sri Lanka. Colombo: International Center for Ethnic Studies.

Helland, Christopher 2013. Popular religion and the World Wide Web: A match made in (cyber) heaven. Religion online, London: Routledge

Kapferer, Bruce 1983. A Celebration of Demons: Exorcism and the Aesthetics of Healing in Sri Lanka. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Obeyesekere, Gananath 1984. The Cult of the Goddess Pattini. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reed, Susan 2010. Dance and the Nation: Performance, Ritual, and Politics in Sri Lanka. Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Scott, David 1994. Formations of Ritual: Colonial and Anthropological Discourses on the Sinhala Yaktovil. London: University of Minnesota Press.

Simpson, Bob 2004. On the impossibility of invariant repetition: ritual, tradition and creativity among Sri Lankan ritual specialists, History and Anthropology, 15:3, 301-316.

Simpson, Bob. 1997. “Possession, dispossession and social distribution of knowledge among Sri Lankan ritual specialists”, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 3 (1): 43–59.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions | Pandemic Leftovers | All Posts

Premakumara de Silva is the Chair Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at the Department of Sociology, University of Colombo. He also a Senior Research Fellow at University of Birmingham, UK and was an Adjunct Professor at Deakin University, Australia. He has published a number of books, chapters and over fifty articles on Buddhist religion, pilgrimage and rituals with reputed international publishers on his credit. Most recently (2024) ‘Research in the digital age: Adopting digital methods in humanities and social sciences research in Sri Lankan universities’. E-Learning and Digital Media, Sage Publication. prema@soc.cmb.ac.lk