Borrowing Gold, Bothering Hindus? The Pandemic as not (quite) an emergency in India

contributed by Swayam Bagaria, 19 August 2020

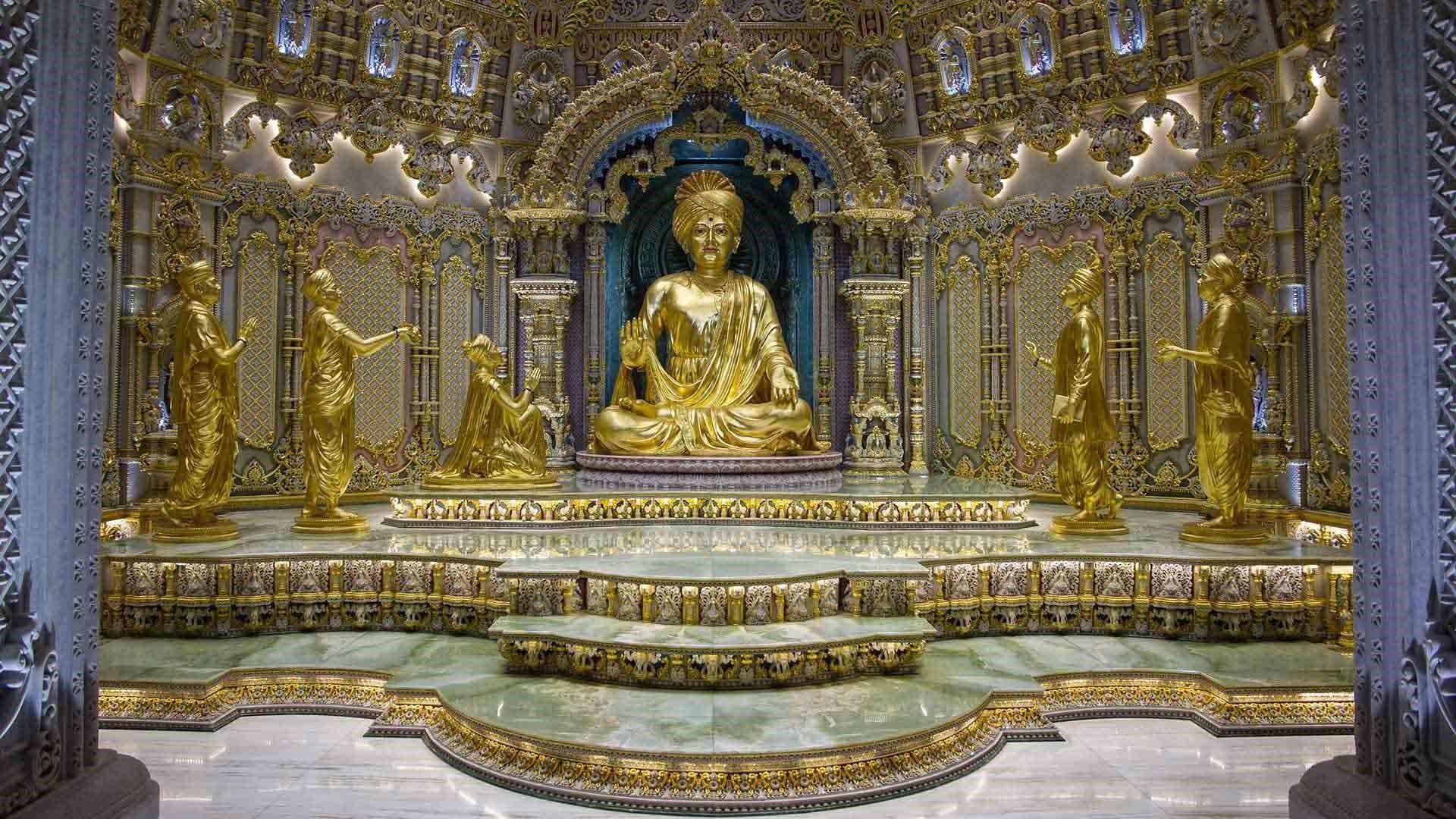

Fig. 1. The main shrine of the Akshardham temple in New Delhi, India, with the gold plated idol of Bhagwan Swaminarayan. More opulent shrines are also an indication of a transition from the storage to the display of gold and the devotional potency associated with it. Source: Swaminarayan Akshardham

In early May, when the plight of the migrant workers had already cut a sordid picture of the Indian government’s botched handling of the national lockdown, a few public personalities floated a solution for a partial economic reprieve during the pandemic. M.K. Venu, a founding editor of the online news and opinion website ‘The Wire’, and Prithviraj Chavan, a senior minister in the Indian National Congress, separately proposed that the Indian government should convert the gold deposited in the thousands of Hindu temples into bullion. This could be done either by borrowing the gold deposited in the Hindu temples through gold bonds at a low interest rate or by persuading the temple authorities to lend gold to the Reserve Bank of India who could then monetize and lend the money to the central government for emergency expenditure.

Fig. 2. Some of the inventory found in one of the chambers in the Padmanabhaswamy Temple after the 2011 Supreme Court ordered to open all but one of their vaults for inventory. This discovery insinuated a worldwide coverage of the ‘hidden’ temple gold of India which only led to an encouragement of further apocryphal statements about the extent of temple gold stocks. The World Gold Council also released a Report around the same time estimating the amount of gold in the temple to be anywhere between 3000-4000 tonnes. Source: Jim Dobson, Forbes

The shelf life of this suggestion, however, was short. The public discussion expectedly solidified around the issue of selective government intervention into the institutional space of the Hindu temples and why their holdings were being uniquely targeted as opposed to that of mosques or churches. First, there is the serious issue of treating temple gold as raw metal rather than artisanal and antique objects that were devotionally offered. Furthermore, the knotty and anomalous involvement of the central and state governments in the managerial affairs of places of religious worship, particularly Hindu temples, is no secret. Even then, framing the problem as an issue of religious freedom misses a practical aspect - it is much easier and swifter to facilitate financial flow by borrowing gold than it is, let’s say, by monetizing unused church land. This is why the place of gold in the Hindu temple becomes significant.

Chavan’s and Venu’s suggestion was not unprecedented and part of the reason for this lies in the sustained attraction of successive Indian governments for marshalling gold into a national resource, especially in times of emergency. The attraction goes as far back as 1962, when the depletion of the gold reserves in the aftermath of the defeat during the Indo-China war resulted in the then Indian government attempting to convince citizens to deposit gold in banks in exchange for bonds. A more recent example comes from 2013 when the value of rupee was fast depreciating and the current account deficit had ballooned. The Reserve Bank of India had then requested several prominent temples to allow them to inventorize their gold holdings, a request that too was blocked.

These efforts are not unique to India. One thinks of the national gold-collection campaign in South Korea in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. More than a quarter of the population of South Korea gave away their personal gold as part of a mass donation campaign to save the nation from an economic crisis. This gold was collected, melted into ingots, and then sold in the international market to begin paying off the country’s debt of $58 billion to the IMF. India, on the contrary, has never quite succeeded in inspiring a national sentiment even though the desire has always persisted.

Fig. 3. The Chief Minister of Telangana, K Chandrasekhara Rao gives gold offerings worth 5 crores (approximately) as per his earlier promise during his agitations for separate statehood for Telangana. Source: FE Online

The efforts to bring gold into public circulation have a rationale. In the jargon of economics, gold is considered to be a “dead investment” that only leads to hoarding. If we couple this particular assessment of gold with the absolute centrality and pervasiveness of gold offerings in the ritual and devotional life of Hindu temples, then it becomes clear that the temple becomes perceived as a place for constricting rather than facilitating the flow of wealth. This is redolent even in the regularly expressed astonishment about the wealth of temples in India, a country that is otherwise still afflicted by widespread poverty.

Perhaps, this is also why Chavan’s and Venu’s suggestion did not get any traction. It was based on a spurious understanding not only of religious freedom, but also of salience of the Hindu temple. Several governmental schemes and policies have been implemented over the years to enable temples to swap gold deposits for sundry investment instruments. However, the little effect it has had is often attributed to overt governmental pressures on the temples under their jurisdiction.

Crucial here is the difference between the temple as a site for charitable provisioning and the resources of the temple as being available as public goods. Over the years, temples have actually increased their forms of provisioning as a response to a more pronounced growth of inequality and competition. This provisioning has, however, gone hand in hand with a more concerted defense of the claims to ownership of its resources.

Fig. 4. Gold brick sent by the Sri Lankan Parliament member Sri Sennathambi to Ayodhya for the inauguration of the Ram Temple. Source: Twitter

No doubt that the pandemic is a situation of unparalleled emergency. But, if the pandemic creates urgency on the one hand, it also leads to entrenchment on the other. The prominence of the Hindu temple as providing the orientation for mass religious aspirations has only become more firm in these past few months, whether through the Supreme Court’s decision to restore the management of one of the richest temples in India, the Padmanabhaswamy Temple, to the royal shebait, or in the immoderate scale and passion with which the inauguration ceremony of the Ram temple in Ayodhya on August 5th was nationally broadcasted. It is worth paying attention, in these times of uncertainty, to the streamlined ways in which mainstream religions are also non-compromisingly doubling down. The conversation that never happened after Chavan’s and Venu’s cursory remarks means that the temple is incontrovertibly here to stay in all its lavishness. It also means that in the more extended temporal arc of Hinduism and despite all the apocalyptic invocations one might hear, the pandemic will hardly be the end of the world.

About Author

Swayam Bagaria received his PhD in cultural anthropology from Johns Hopkins University. His research is on the relation between popular Hinduism and political populism in contemporary India.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions