What’s in a Heart? Expressions of Thanks as a Form of Public Morality

contributed by Emily Hertzman , 3 October 2020

The first case of COVID-19 in Canada was recorded on January 25th 2020. By mid-March the country, like much of the rest of the world, was in lockdown with citizens instructed to stay home - not to go to work or school, and not to venture outside except for food, supplies or essential medical appointments. Citizens were asked to wear masks, wash their hands regularly, avoid touching their faces, and most importantly, to socially and physically distance themselves from other people in order to stop, or slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. Schools, public offices, museums, galleries, community centers, gyms, libraries, malls, shops, bars, hair salons, nail parlours, churches, mosques, synagogues and temples etc. were all shut. Suddenly, practically overnight, the streets of cities and towns across the country were vacated. Everywhere was like a ghost town, with few people on the sidewalks, almost no cars on the roads, not even planes in the skies. It was an altered reality.

People stayed inside their homes. Some panicked and bought tons of supplies like meat and toilet paper, emptying the contents of grocery stores into their shopping carts, leaving an appearance of scarcity on store shelves unseen since the great depression. Thousands of people were laid off, whereas some adults resumed work from home. Parents tried to manage homeschooling their children while working from home. Seniors and others in long-term care facilities, and their healthcare workers, became the most vulnerable populations: many people died, often alone, very quickly and without being able to see their family members. It was tragic and traumatic, and the public, even those unaffected directly by the lethal virus, sensed that something terrible was going on. Federal and provincial health officials kept citizens abreast of everyday epidemiological developments with daily press conferences. But what outlets existed for the public to deal with how they were feeling about this all? One thing that began happening right away was a proliferation of homemade window displays of hearts and messages of thanks to frontline and essential workers, which expanded into a general public outpouring of love and support.

In the photo essay that follows, I document some of the homemade signs made during the COVID-19 lockdown and offer a preliminary (and partial) interpretation of these signs, suggesting that the mass display of handmade hearts in peoples’ windows are best thought of, not only as a secular outpouring of support for frontline workers, but also as a collective expression of hope and a public morality based on the need for love, care and kindness.

The heart is a ubiquitous symbol of romantic love, particularly around Valentine’s day, with malls, grocery stories, flowers shops, lingerie stores, jewelers stores and dollar stores all seasonally flooded with heart-centric displays, decorations and merchandise. The heart is also a long-standing Christian symbol, particularly in the Catholic Church where the ‘sacred heart of Jesus Christ’ is an elaboration of a set of teachings, based on the love and compassion of the heart of Jesus Christ towards humanity. Most recently, the heart is an omnipresent icon on social media platforms where many users spend large parts of each day assigning likes and tapping to give hearts to people’s accounts on their various streams. Many emojis feature hearts, including the “love” and “care” emojis from Facebook, and have now become regular part of peoples’ daily communication on Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, Snapchat, text messaging and email. However, the hearts that began to fill windows of houses and apartments during the lockdown were clearly and recognizably signalling something else, not romantic love, not religious affiliation, and not social media support, but perhaps a hybrid of these all. The hearts represent a secular empathic love, an expression of thanks, and a symbol of hope. The start of this campaign of hearts can be traced to two social media campaigns, Hearts in the Window Facebook Group and A World of Hearts Facebook Group, which promoted the idea of sharing hearts as a way of spreading love and hope in uncertain times. This call was answered by many individuals in isolation as well as by teachers and parents involved in remote and online schooling who began to encourage children to make hearts and messages for windows, as both an outpouring of support and as a craft project to keep them busy.

Hearts in the Window

Handmade Hearts in House Windows. Source: Emily Hertzman

Homemade Signs

Alongside the handmade hearts, people began to put homemade signs in their windows or on their lawns, with messages of thanks for essential workers, and broader calls for kindness and hope.

Left to right - “Not All Super Heroes Wear Capes. Thank You to all our Health Care Workers, First Responders, Front Line and Essential Workers.”, “Kindness puts hope in people’s hearts”, “No act of kindness is ever wasted”

Left to right - “Emergency workers rock”, “Thank you to our essential workers”

Heart Nationalism

Building on the theme of hearts, a local newspaper in Victoria, British Columbia, The Times Colonist, decided to print a Canadian Flag which replaced the central maple leaf, the dominant symbol of Canada, with a heart as an expression of solidarity, thanks and hope. The flag was printed in the newspaper and members of the public could cut it out and display it in their windows. This was later picked up and spread beyond Victoria, BC. The heart, thus, took on another layer of meaning as its symbolic dimensions as an expression of thanks and hope got coupled with national pride and national identity.

The heart flag was also picked up by other more corporate enterprises. It is seen here as a wall mural on the side of a broadcasting building next to the CBC logo, another prominent Canadian symbol

Cute Signs

Businesses, particularly small and independently owned businesses, have been making cute, unique and original signs for a long time. These signs are often hand written in chalk on sandwich boards outside shops and cafes and usually state some humourous or cheeky play on words related to the stores’ products like “beauty is in the eyes of the beer-holder”, or “pilates? I thought you said pie and lattes”. During the lockdown, as most businesses were closed temporarily and many others shutting down permanently, the sandwich board signs disappeared and then slowly began to return with more positive messages, communicating hope and togetherness. The heart was used as a symbol in these signs as well.

Left to right - “We’re all in this together”, “You’re wonderful human beans (heart) victoria grocery staff”, “Welcome. Kindness is cool”

As seen below, other small businesses joined the Hearts in the Window movement by adding their own artistic decorations to store fronts.

Left to right - “We are open”

Public Sector Signs

As society began to reemerge over a three-stage reopening of the economy, both public and private sector enterprises had to design their COVID-19 safety protocols, which includes perfecting their signs and message boards. Calls for social or physical distancing, a term that most Canadians learned for the first time in March, is now represented everywhere from buses to malls, libraries to beaches. The government messages are clear, concise and appear standardized which marks them as official and legal.

Examples of notices calling for citizens to maintain their social distance in public spaces

These official signs command citizens to be “mindful” and “do our part,” invoking the idea of cooperation, participation and togetherness at a time when people, in fact, face enormous barriers in their ability to connect. The irony of this is not lost on the sign makers, who play with the words of being together while apart. The messages, while primarily public health related, take on an ethical dimension that asks citizens effectively to be good, to be righteous, and to be true by following these rules, and following them not only because it is a civic duty but because it is the characteristic of an individual and societal moral norm.

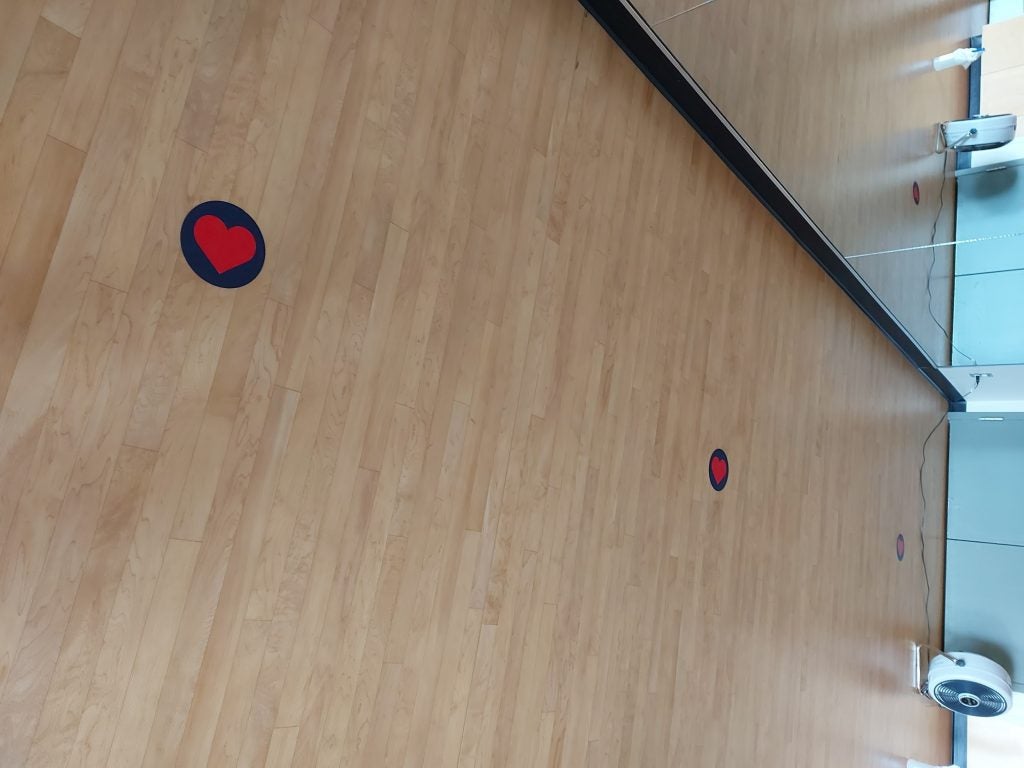

Hearts used to measure physical distancing at a public community center

Private Sector Signs

Signs in the corporate sphere also echo the public-sector messaging, but have a familiar branding and advertising quality to them. These signs try to be clever and positive, while using the same messages of togetherness, mindfulness, and kindness. One sign even goes as far as suggesting people should “smile with their eyes” - a direct reference to mask-wearing, which we can interpret as a way of asking people to be happy and adopt a positive outlook despite the abnormal and unfortunate circumstances caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Left to right - “Be kind and wear a mask”, “Stand Together by Standing Apart”, “Please Be Mindful of Your Neighbour”, “Smile with your eyes”, “Choose kindness”

Public-Private

BC’s Provincial Health Officer, Dr. Bonnie Henry, has become a local celebrity for the way she has effectively and calmly dealt with the COVID-19 crisis in the province by communicating with the public daily. There are t-shirts printed saying, “I’m with Bonnie Henry,” and BC Science World, a public-private consortium, is using a photo of her as a 7-year old girl in their new fundraising advertising campaign.

Poster with a childhood photo of Dr. Bonnie Henry captioned: “The world needs more nerds”

In the midst of a crisis, citizens are asked to stay hopeful, to focus on the future and, in this ad, to ‘fund to the future’. Across all of these secular calls for hope, happiness, gratitude, togetherness, mindfulness and kindness, we are reminded of another very prominent, very prolific, and very popular source of moral and ethical inspiration: religious institutions.

Christian Signs

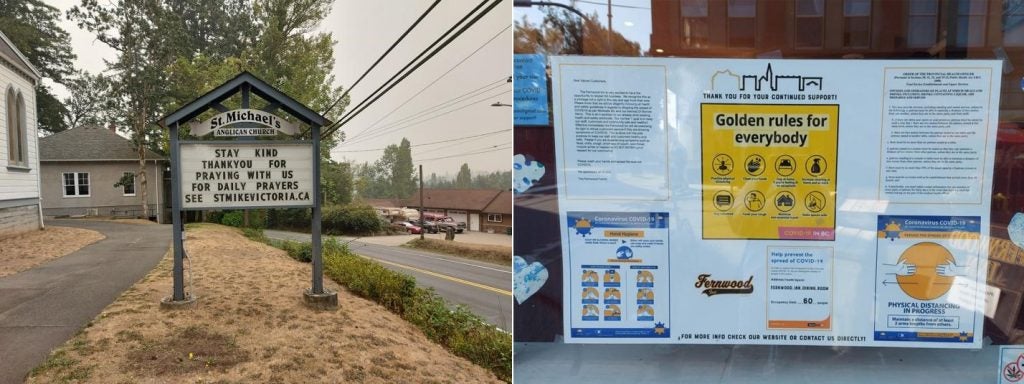

The messages on Church signs and doors are practically identical to the messages circulating in the secular public sphere. These place an emphasis on the heart, on being safe and calm, and most importantly on being kind. It is a veritable echo chamber of symbols and messaging spanning sacred and secular spaces, and communities.

Left to right - “Being apart means we’re together through this”, “Welcome back. Some things have changed, but not our hearts.”

Left to right - “Be kind, be calm, be as loving as Jesus Christ”, “Be Kind, Be Calm, Be Safe”, “We are staying safe. Be Calm. Be Kind.”

“Stay kind. Thank you for praying with us.”

“The golden rules for everybody”, one sign reads, is not perhaps the Golden Rule as stipulated in the Bible, but nonetheless indexes that moral authority and is conveniently reimagined as a set of proper protocols to handle the risks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Citizens are asked to follow the rules not simply because they exist, and not simply for the sake of public health and safety but also because it is ‘the right thing to do.’ The rules are presented clearly as a matter of popular secular morality.

The heart is a complex, multi-dimensional symbol which has come to signify many things spanning a continuum of secular to religious meanings. Most recently, the heart has been repurposed as a symbol of hope and gratitude, by thousands of people isolated in their homes trying to understand how they should or could act and what they were feeling during the most extraordinary pandemic conditions in modern Canadian history. The heart quickly took on multiple meanings, by being linked to national identity and expanded from individual use to business and corporate use. Alongside the hearts were repetitions of messages which reveal an attempt by individuals to articulate an ethic of best practice for uncertain times. The need for kindness, something seemingly unrelated to the novel coronavirus, emerged as a predominant theme - a phantasm of a Christian moral foundation upon which most of the normative Canadian civil society is built. While decoupled from these direct origins, the flood of hearts, written signs and their implicit moral messages suggest that during this crisis more than ever people are seeking outlets to express and define their aspirational ideals and best moral practices. This is an articulation of what it means to be a good person, a good citizen, a good neighbour, a good community member, and a good Canadian, which builds on an performed national imaginary of the quintessential kind and peaceful Canadian. While hearts on windows may not seem like radical action, protest, or even a very efficacious form of support, it is an important subtle and symbolic way for people to express themselves while undergoing isolation at a time of crisis.

Emily Hertzman is a sociocultural anthropologist whose research focuses on Chinese Indonesian mobilities and identities. She received a B.A and M.A. from the University of British Columbia and a Ph.D. from the University of Toronto (2016). She will be joining the Asia Research Institute in the Religion and Globalization cluster at the National University of Singapore as a Research Fellow in 2021.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions