Religious Televisuality in the Time of Pandemic

contributed by Louie Jon A. Sánchez, 30 October 2020

The Philippines is now on its sixth month of quarantine, hardly flattening the curve, no matter the spin of a government severely criticized for its politicking and misplaced priorities in the middle of the COVID-19 health crisis. The past few weeks registered new cases of about 2,000 to 3,000 daily and the general mood remains bleak, despite concerted efforts to slowly open the economy and normalize daily life.

As churches began reopening in July 2020, the Philippine Catholic Church expressed relief that access has been expanded to 10% of the church capacity. The devout began returning to churches with health protocols strongly in place.

The Church considers its mission vital for the wellbeing of the Philippine population’s Catholic majority, as it intends to provide solace and strength. This, the Church upholds even as some members of clergy themselves acquired COVID-19 while in mission, and had passed away in the process. One of them was the former head of the Catholic Bishop’s Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), Archbishop Oscar Cruz, an advocate of social justice and a staunch government critic.

Former Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle, who had recently flown back from Rome to Manila for a short leave from his post as prefect of the congregation for the evangelization of peoples, has just recovered from the virus, supposedly contracted on his way back to the country. Opening up about his experience in isolation, he told an audience of local Catholic educators in a conference that he struggled with “fear and anxiety” as he also came to terms with the need for “interconnectedness,” now more than ever.

‘Religious Televisuality’ online still the norm

Despite the government’s easing of restrictions on religious gatherings, many Catholics still rely on social media to connect with the Church, continuously accessing rituals now being presented “televisually” by a growing number of churches with improving broadcast equipment and streaming technology.

Religious televisuality, which I earlier called “Catholic liturgical televisuality,” is the current use of televisual technology and platforms by religious institutions to conceptualize, produce, and disseminate religious content for use of, and sharing by the faithful. The primary platform at the moment is social media, specifically Facebook, and this is very crucial at this time for the Catholic church in the Philippines, which has limited TV broadcast resources and facilities.

Religious televisuality relies on the charity of the faithful and the kindness of ancillary social media platforms, composed of parish or organization Facebook accounts, to extend its reach. Social media then becomes a complex of what may be called “polychannels” where televisualities are digitally iterated, and broadcasting flow directed and redirected not only by institutions but also by people utilising the platform as they view and share religious contents. Religious televisuality is now being harnessed by the Catholic Church, as well as other churches in the Philippines which I hope to report about at another occasion.

As a technological necessity borne of the pandemic, religious televisuality becomes another "means of communication of which (its) nature can reach and influence not merely single individuals but the very masses and even the whole of human society," as the 1963 landmark Catholic encyclical Inter Mirifica puts it. It’s also a breakthrough in a way, as it shows the Church's resilience in ensuring, in the words of the same social communications document, that "the means of communication are put at the service of the multiple forms of the apostolate without delay and as energetically as possible, where and when they are needed."

Two Catholic churches in the Manila capital region that have been streaming rites daily since the March lockdown—the Manila Cathedral, the seat of the Archdiocese of Manila; and the Santo Domingo Church, also known as the National Shrine of Our Lady of the Most Holy Rosary, La Naval de Manila of the Dominicans—still continue to draw Catholics online, especially during Sunday masses. Both have also expanded programming to catechesis and other social communication advocacies. The same may be said about the Jesuits which maintain inspirational and musical programs, as well as daily masses, from the order’s social media platforms.

Some parishes have also engaged in localized streaming of masses, often utilizing makeshift online broadcast equipment. Like the ones streamed by the above mentioned, these adhere to the May 2020 CBCP recommendations and guidelines for liturgical celebrations, anchored on the Church’s “"pastoral sense and love for our flock.”

Fig.1. The Diocese of Maasin streams on Facebook a night mobile benediction of the Blessed Sacrament in its cathedral’s locality. As the motorcycle speeds through the roads, a bell may be heard ringing as prayers are being delivered through a megaphone. (Screenshot taken by the author from Facebook)

The said efforts are sometimes coupled with neighborhood or house-to-house visits, where parish priests administer the sacrament of the Holy Communion, sought by the faithful after being inaccessible for months. Some even bring the Blessed Sacrament to localities, like the Diocese of Maasin, in the Visayas island of Leyte, which mounts a night motorcade that streams the exposition on Facebook aside from masses at the Maasin Parish Cathedral. The diocese also takes pride in its social media campaigns marking the 500th Year of Christianity in the Philippines in 2021. Under its jurisdiction is the island of Limasawa, historically the site of the first ever mass in the country in 1521.

In general, the Church relented to state restrictions from the start, even assisting in stay-at-home and health protocol campaigns, while also attending to charity work that has never been more urgent and demanding. A very notable effort is the well-sustained feeding program under the auspices of the Redemptorists’ National Shrine of Our Mother of Perpetual Help in Baclaran, Parañaque City, Metro Manila South. From streaming online masses and its sought after Wednesday novena to the miraculous Marian icon it houses, it also works with civil society groups to feed not only the homeless, but also medical frontliners and stranded citizens who decided to wait on the state to bring them home to their provinces in airport terminals within the vicinity. It has also opened the church and its complex as a shelter for the homeless.

Fig.2. Baclaran Update Report - The Baclaran Church accounts for donations received, as well as its beneficiaries, in this information sheet posted on Facebook (Screenshot taken by author from Facebook)

People also continued to depend on streamed masses and prayers when the capital was once again placed under stricter lockdown measures in August 2020, amidst clamors by the healthcare community for a “time out” as recorded cases spiked. In solidarity, 10 Catholic dioceses immediately suspended public masses, barely a month after these have been resumed. Two dioceses, that of Cubao and Parañaque in Metro Manila, released suspension orders ahead of government response that enforced the two-week “time out.”

Bishop Broderick Pabillo, apostolic administrator of the Archdiocese of Manila, himself a COVID-19 survivor, emphasized in a pastoral instruction that the Church “(shares) the compassion of the medical frontliners for the many sick people being brought to our hospitals.” He continued: “We have witnessed their dedicated service to those who come to them. Many among them are tired and even discouraged by their heavy responsibilities.” For his part, Cardinal Tagle, still in Rome during that time, offered an online spiritual recollection for frontline workers.

Other Catholic churches have also found creative ways to bring rituals and sacraments to people by way of social media. Countless processions of miraculous icons have already been streamed and viewed on social media, increasing fervor especially in these very difficult times. The Visayas island region’s Santo Niño de Cebu [The Christ Child of Cebu], the country’s oldest Catholic icon under the care of the Augustinians, was brought around Cebu City to visit neighborhoods and hospitals by a night motorcade team that also streamed its sojourn through the shrine’s social media page. People in physical distancing greeted the well-loved image as they raised their hands or knelt in supplication—very moving gestures all captured online, as well as in a documentary video by Caloy Ramirez (as seen below).

Video: Caloy Ramirez produces this video documentary featuring the night motorcade of the Santo Niño de Cebu around Cebu City

As fiestas or local commemorations of saints’ feast days are indefinitely postponed, Catholic shrines have also used social media broadcasting to bring celebrations to the faithful at home. The Archdiocese of Caceres in Naga City in the Luzon island’s Bicol region scrapped its annual September fluvial and street processions of the centuries-old miraculous Our Lady of Peñafrancia and its accompanying image of the El Divino Rostro [The Holy Face of Jesus]. Instead, parishes under the archdiocese viewed the novena [nine-day] masses via online streaming. They were also treated to other programs like a musical concert and even video documentaries of past fiestas.

Back in Manila, the Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene, home to another popular centuries-old icon, the Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno - an icon of Christ carrying the cross - has long been engaging in streaming even before the pandemic. The church located in Quiapo in the old Manila business district annually gathers millions during its street procession in early January.

Fig.3. The replica of the Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno, the Black Nazarene of the Quiapo Basilica in Manila, venerated in a September 2020 procession and only protected by a glass canopy from the rains and the elements. (Screenshot taken by the author from Facebook)

As quarantine restrictions were lifted, Quiapo Basilica administrators allowed the prescribed number of people into the church. Resumed traditional Friday devotions to the Nazareno also began attracting devotees once again - many contented just by standing outside the church plaza during masses, in strict social distancing and in required face masks and shields.

Meanwhile, the practice of pahalik [“to kiss”], the kissing or touching of the exposed foot of the Nazareno remains to be prohibited. Instead, administrators offer the alternative patanaw [“to present for viewing”], where devotees venerate the image from afar, and even through replicas in designated areas. As administrators held a procession of the icon around the church’s vicinity much earlier in September 2020, they also announced preparations for the coming fiesta in January 2021, once public gatherings are allowed by the state.

Fig.4. Not even the downpour prevented Black Nazarene devotees from joining the down-scaled procession of the icon, wrapped in transparent plastic, around the Quiapo Basilica in Manila (Screenshot taken from the author from Facebook)

Meanwhile, nightly recitations of the holy rosary have also become a fixture in pandemic televisualities, catering to people’s need for a deeper prayer life. The Manila Cathedral regularly hosts “Healing Rosary for the World,” where the clergy lead the prayers and showcase Marian icons and devotions from different shrines in and around the capital—thus offering a virtual pilgrimage.

Fig.5. The Manila Cathedral’s Healing Rosary for the World series offered a virtual pilgrimage to different Marian shrines as it also propagated a return to the rosary devotion during the pandemic (screenshot taken by the author from Facebook)

Virtual church doors have also been left open to the public by several religious orders as their members streamed community recitations of the rosary online. It may be argued that the holy rosary has become a relevant practice once again in the Philippines, with families and communities gathering up for nightly devotions. The devotion is accentuated by the recitation of the earlier issued oratio imperata against the pandemic, which also helps popularize devotion to the two Filipino saint-martyrs Lorenzo Ruiz and Pedro Calungsod; as well as prayers formulated by Pope Francis himself in April 2020.

Interconnectedness

As community worship and practices remain very limited, religious televisualities through social media help in maintaining what the Cardinal Tagle described as interconnectedness—that is, among the Catholic faithful simultaneously tuning into the Facebook pages of their selected churches, and between this virtual community and the Catholic Church.

In his aforementioned sharing, Cardinal Tagle reiterates that "(y)our existence depends on a rediscovery of the reality that you are not alone, you are always connected.” The Catholic Church's pivot to online platforms during this health crisis, and amidst a socio-political pandemic of suppression and misgovernance, makes interconnectedness all the more an important, constant aspiration.

Through a new medium, and a framing that is portable and safer at this time, the Church is enabled to transcend its institutionality, returning once more to its roots of bringing together and mobilising people as it touches base with its community of believers estranged by social distancing and increasing uncertainty. And as people are brought together under the Church’s virtual roof, charity, faith, and hope are at once renewed, which hopefully create more dialogue and social action—interconnectedness manifested, even in physical distancing.

As the country ushers in the Christmas season, perhaps the longest in the world as it begins in September and ends in January, Filipino Catholics could not help but feel doleful with the possibility of not being able to attend the usual mid-December novena masses called misa de gallo [traditionally done at the crack of dawn, as signified by the crowing of the gallo, the rooster] until Christmas Eve. At this point, religious televisualities provide an alternative means to carry out the devotion in the time of pandemic, the completion of which is said to come with wishes fulfilled. Could a collective wish for the pandemic’s immediate resolution bring the much prayed for miracle?

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Louie Jon A. Sánchez is assistant professor of English at the School of Humanities, Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. He teaches writing, literature, popular culture, and television studies. He is associate editor of Suvannabhumi, a multidisciplinary journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Korea Institute of ASEAN Studies, Busan University of Foreign Studies.

Other Interesting Topics

Inverted Sociality: Muslim Indonesia Celebrating Idul Fitri without Mudik

Idul Fitri 1 Shawwal 1441 Hijri has just passed. In contrast to previous years, this year left a very deep impression for Muslims in Indonesia. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to new ways of celebrating holidays. Muslim Indonesia’s tradition of going home or “kampong halaman” (called mudik) and hospitality (called unjung-unjung) that is usually carried out...

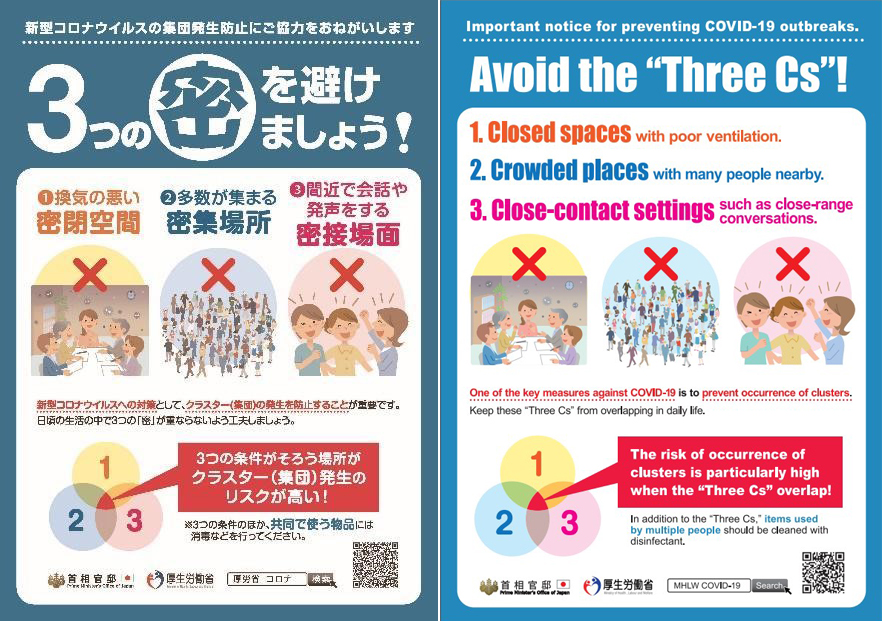

3-Cs and the Three Mysteries: Japanese Esoteric Buddhism’s Response to the Covid-19 Pandemic

How does religion make sense of the Covid-19 pandemic and rearticulate its relevance for a society where close-contact social life has been drastically reduced and people primarily communicate by digital means? In formulating innovative ways to engage society during the Covid-19 pandemic, esoteric Buddhism..