Walking a fine line: Churches respond to COVID-19 in rural Indiana

contributed by Michel Chambon and Erica M. Larson, 5 November 2020

Churches in the United States (US) have made global headlines for refusing to close their doors during state-wide mandated shutdowns and for contributing to coronavirus outbreaks, particularly when failing to follow protocols from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These portrayals convey the sensitive political nature of the COVID-19 response from faith communities, but have focused on the most extreme cases.

Through ethnographic data from rural Indiana, we recount the overall nuanced approach to dealing with the myriad of concerns that COVID-19 has posed for Christian communities in terms of gathering (in-person or online), performing religious rituals, and helping congregants facing economic hardship. As the COVID-19 response has become an increasingly politicized issue in America, most churches in Jefferson County, Indiana, continue to walk a fine and increasingly exhausting line in terms of their dynamic responses to both the health-related concerns and the polarizing impacts the pandemic has had in the US.

Jefferson County, Indiana, is a mostly rural county with a population of just over 32,000. At the same time, more than a third of its inhabitants are concentrated in Madison, Indiana, a city on the Ohio River that was historically important as a port connecting trade routes between northern and southern states. Proud of its heritage, the city cultivates a very dynamic cultural life and maintains a fairly robust economic backbone. Although Madison remains small in size, its charming historic downtown and regular festivals draw tourism from surrounding areas. It remains connected to nearby cities by virtue of its location at the center of a triangle formed by Louisville, Cincinnati, and Indianapolis. In tune with its regional environment, a majority of the population identifies politically with the Republican Party.

Image 1: A regular Sunday service at a Presbyterian Church in Madison (Photo credit: Michel Chambon)

Churches play a central role in the social, political, and economic life in Jefferson County. There are approximately 70 independent churches varying in size from approximately 15-300 congregants attending on a given Sunday. In addition to Baptist Churches, there are many other denominations represented, including Methodist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Episcopal, Mennonite, Pentecostal and Evangelical traditions, and one Catholic parish. While the vast majority of the population identify as Christian, participant observation and interviews across the wide spectrum of local Christian communities suggest that approximately 40% of the county's residents attend a church service every Sunday.

Phase 1: Shutdown (late March to May)

The arrival of the novel coronavirus in the US took people from Jefferson County by total surprise. In early March, they—like most of their fellow citizens—had little idea of what was happening in East Asia. Then, almost over the course of a single week, what had been portrayed as a “foreign” virus became an American reality. From mid-to-late March, churches, educational institutions, and businesses mostly flipped from a steadfast position of continued in-person meetings and regular store hours to sudden closures. On March 25, 2020, when a ‘Stay-at-Home’ order for the state of Indiana went into effect, COVID-19 cases had already begun to climb in metropolitan areas, while Jefferson County had yet to confirm a single coronavirus patient.

Image 2: On March 15, 2020 a Pentecostal congregation in Madison prays by coming to the altar as a group, asking for God to handle the coronavirus (Photo credit: Michel Chambon)

Caught utterly unprepared, churches of different sizes and with various levels of tech-savviness and equipment were left with no choice but to quickly explore options for transitioning services online. The largest churches in Madison already regularly live-streamed Sunday worship and were able to immediately switch. Smaller communities and those with more elderly congregants were slightly delayed in going online. But most explored options and offered some form of online spiritual support within a week of the shutdown.

The impacts of moving services online were not consistent across congregations. While smaller groups were typically less technologically equipped to make a quick transition, their size made it easier to check in on one another through phone calls before and after their virtual services. Larger churches, by contrast, quickly shifted online but had to find other ways to foster fellowship among their members. With the comforting presence of the vibrant Sunday congregation conspicuously absent, pastors and leaders had to promote other ways of communal belonging that could reinforce a sense of mutual support.

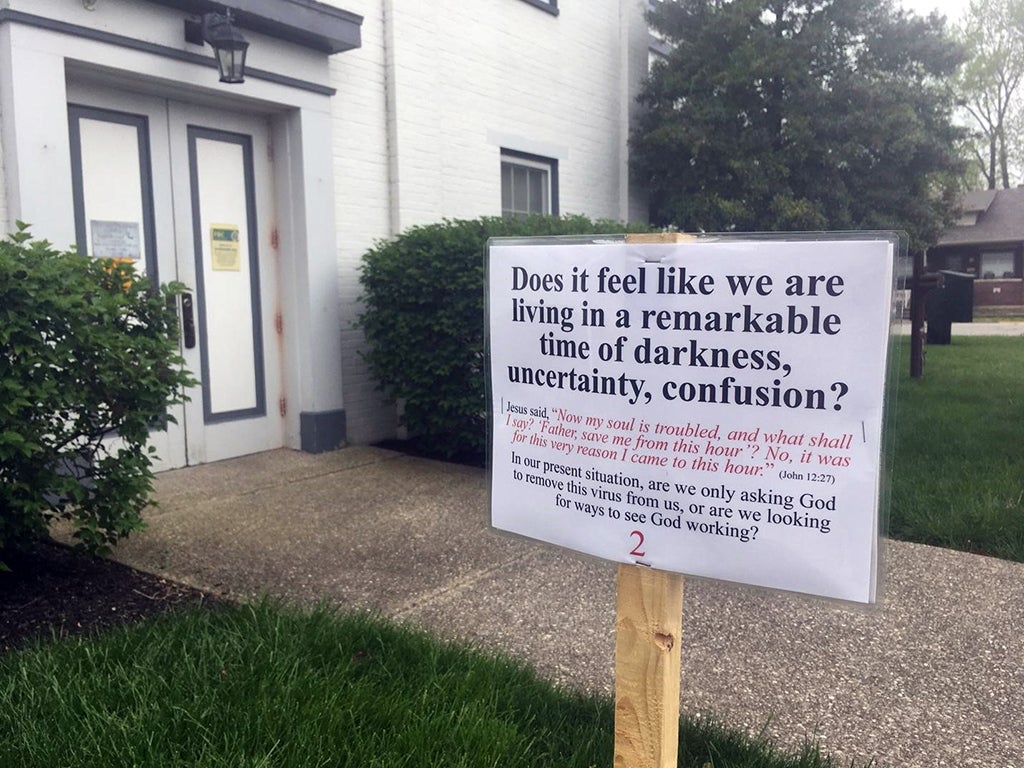

Image 3: A sign posted in front of a Baptist Church in Madison in April 2020 (Photo credit: Michel Chambon)

Denominational differences also influenced the facility of translating liturgical requirements to virtual spaces, particularly in terms of encountering the sacred and performing Holy Communion. For Evangelical and Baptist traditions, the body and blood of Christ are more significant in their metaphorical dimension than their material aspects. These pastors did not hesitate to encourage virtual congregants to be creative in selecting food/drink items to be blessed remotely and consumed conveniently. Others, like the Lutherans, recommended that only bread and wine would be acceptable choices. Episcopalians, with specific liturgical requirements for the Eucharistic service, opted to have only morning prayer for their online service and not partake in Holy Communion.

Similarly, attending in-person church service does not bear the same level of obligation among all Christian traditions. While many Christians may claim—often against what their pastors tend to say—that praying in one’s heart can sufficiently replace physical church service, this posed a particular problem for the more legalist American Catholicism. Therefore, in addition to the broadcasting of masses on Facebook by most local parishes, Indiana bishops released a dispensation from the obligation to attend weekly mass.

Despite President Trump’s assertion that Easter (April 12, 2020) would be a ‘beautiful time’ to reopen the country, the stay-at-home order for the state of Indiana was twice extended, ultimately only ending on May 1st. Statewide, religious services were allowed to resume with no cap on attendance starting May 8th. These shifting policies set the stage for legal battles against counties and cities which implemented limitations on the number of people allowed at religious gatherings, arguing their claims on the basis of religious discrimination.

Image 4: A yard sign in Madison showing support for front line workers (Photo credit: Michel Chambon)

Nevertheless, case numbers in Jefferson County remained extremely low during this first period of the pandemic. Churches were almost unanimously on board in adhering to state orders and attempting creative responses to look after members in a time of social distancing and national distress. While the virus itself was not yet locally widespread, the economic and social consequences, along with the fear and anxiety anticipating its potential effects, were prevalent among the population. Madison Church boards, pastors, and members worked to support food pantries and adjust their mode of operating to the pandemic environment. They also coordinated to provide rent assistance to those in need, whether directly to church members or through charitable organizations like the Salvation Army.

Phase 2: Slow Re-opening (June to mid-July)

With restrictions on religious gatherings lifted, by early June most churches moved forward to re-functionalize church spaces to follow CDC protocols and limit potential transmission of the coronavirus. Given the warm (though at times sweltering) summer weather, congregations likely to fill their sanctuary opted to meet outdoors. Those with a membership significantly smaller than the actual size of their sanctuary measured church pews, calculating how to seat people while maintaining a minimum of six feet (1.8 m) of distance. Nevertheless, all churches contemplated what to do about singing hymns, whether or not to open their nurseries, how to limit the movement of congregants once inside the building, and whether to maintain an online option.

Left - Image 5: A sign with re-opening protocols posted on the door of the Catholic Community Center in Madison (Photo credit: Michel Chambon)

Right - Image 6: A church in the countryside of Jefferson County with a banner stating “God Bless America” (Photo credit: Michel Chambon)

During this early summer phase, political polarization regarding the virus response began to reveal and exacerbate social tensions on a national level. Face masks became a highly contentious and politically divisive issue. For many politically conservative Americans, face masks symbolized giving up individual freedom, allowing government overreach in citizens’ personal lives, and opening dangerous precedents for tyranny. In Indiana, mask requirements were initially mostly imposed on a case-by-case basis by private businesses.

In Jefferson county, case counts remained extremely low until mid-July. Daily case counts had never been higher than four, and were most often one or zero. The anti-mask sentiment, which existed on a national level, resonated with some in rural Indiana who felt that the attention to the virus was overblown, economic impacts of the virus in the community had already taken too much of a toll, and that the worst was already over.

Church leaders—with their own interpretations of the effectiveness of masks and range of political leanings—in conjunction with church boards and members worked to answer all of these important questions about new protocols. Some dealt with the political nature of masks by avoiding mentioning them altogether or leaving the decision up to individuals. Rather than taking what might be portrayed as overtly political stances by publicly declaring what to do about face masks, some churches implemented new protocols regarding the use of hand sanitizer and distanced seating, but carefully avoided specifying policies regarding masks.

Churches that did include mask wearing in new guidelines for congregants still often regarded doing so as a personal decision, and sometimes wearing masks exclusively while entering or exiting the building was acceptable. Online services were often maintained as an option for those at-risk or those uncomfortable being in an environment with others not wearing masks. Overall, as churches re-opened their doors during this early-summer phase, attendance remained low and uncertainties high.

Phase 3: Resuming vs. Re-Zooming (mid-July to September)

Following the July 4th national holiday, COVID-19 started to spread at higher rates in Jefferson County, recording up to eleven new cases per day. For many residents of the county, this was actually the first time they began hearing about local COVID-19 cases. The pandemic that had already asserted itself as a political and social reality had changed in nature once again. By the end of July, its potential health impacts became increasingly real.

On July 24th, Indiana’s Republican governor signed an executive order mandating face coverings in indoor public spaces. However, the order also specifically exempts those in religious services on the grounds that they are already required to maintain a minimum of six feet (1.8 m) of distance from others in indoor spaces.

Dealing with this new development, churches’ strategies for gatherings became even more varied and complicated. On the two ends of the political spectrum are the congregations which continued in the same track to resume in-person services, and those which decided to move back to fully online worship. However, as health concerns and political leanings are not uniform across individual communities, the “hybrid” model—allowing in-person attendance in addition to an online option— has become most predominant among Madison Churches, just as it has in many American educational settings. Although the virus was locally more present than in March when most churches had closed, this time their response was more diverse.

Image 7: Online service held on Zoom with a Lutheran congregation in Madison (Photo credit: Michel Chambon)

In early August, concerns and worries about school reopening abounded. Discouraged from joining athletic activities or visiting their grandparents, children had been mostly at home since mid-March, and families were exhausted. Yet, the crisis that everyone hoped would quickly pass had regained more strength. Decisions were even harder to make. After four months of staying at home and waiting it out, people began to feel that this was not a long-term solution. The pandemic was becoming something that everyone would have to live with. As late summer arrived and businesses needed to resume, people felt it was time to find a workable solution in a pandemic world. For many, that solution included the ability to join in-person worship services.

Looking for Long-Term Solutions

At the beginning of September, and despite all the remaining uncertainties, schools reopened (mostly under the ‘hybrid’ model) and businesses resumed. Nearly all churches went back once again to in-person meetings, working to adjust to the ‘new normal.’ Still, many continue to offer an online option. Congregations which had creatively provided quintessentially American ‘drive-in’ or outdoor meeting spaces were also being forced to reconsider their options as the weather began to cool down during the fall season.

In October, President Trump tested positive for the coronavirus, and political tensions surrounding the administration’s handling of the pandemic continued to simmer. Close to the presidential election, Jefferson County witnessed a political caravan of more than 100 cars proudly proclaiming support for Donald Trump and his response to the virus. Meanwhile, the prospect of more federal relief is uncertain and the scope of the economic impacts of the coronavirus is extremely unclear. After more than six months of crisis, local churches continue to mobilize their resources to provide material, financial, and social assistance and offer a potential platform for civic cohesion and mutual support.

Not surprising, most inhabitants of Jefferson County agree on one point: people are exhausted by this virus, its constantly changing nature, and all the turmoil that accompanies it. Month after month, its appearance and significance have shifted, and yet, nothing is certain or solved. On top of that, political divisions are constantly increasing and engaging in dialogue is becoming complicated. Churchgoers and their pastors walk this tormented path alongside their fellow citizens. Despite the variety of their responses and congregational situations, they do not have a collective and unique answer, but they continue to dig into their biblical, communal, and spiritual resources to face the many dilemmas brought by the crisis. Given the social upheavals related to the coronavirus and presidential election, churches in Jefferson County, Indiana have mostly walked a fine line, seeking to serve as local spaces of unity in an utterly divided world.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Michel Chambon is a French cultural anthropologist and Catholic theologian focusing on Global Christianity, having studied Protestants and Catholics in China, Europe, and the USA. His recent book Making Christ Present in China: Actor-Network Theory and the Anthropology of Christianity is based on ethnographic research in Fujian, China.

Erica M. Larson holds a Ph.D. in Cultural Anthropology from Boston University (USA). Her research interests include education, religion, ethics, and politics. Her dissertation examined civic and religious education programs at various high schools in North Sulawesi, Indonesia, in order to understand how they become important sites for deliberating the ethics and politics of plural coexistence She will join the Religion and Globalisation Cluster at the Asia Research Institute as a Postdoctoral Fellow in 2021.

Other Interesting Topics

What’s in a Heart? Expressions of Thanks as a Form of Public Morality

The first case of COVID-19 in Canada was recorded on January 25th 2020. By mid-March the country, like much of the rest of the world, was in lockdown with citizens instructed to stay home - not to go to work or school, and not to venture outside except for food, supplies or essential medical appointments...

Grassroots Religio-cultural Elements Protect Rohingya Refugees During Covid-19 in Aceh

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, numerous countries have tightened their sea border controls. In mid-April 2020, 382 Rohingya refugees in the maritime borders of Malaysia and Thailand were rejected entry because of concerns regarding the spread of Coronavirus...