Restless souls: The impact of COVID-19 on the funerary ceremonies of the Parsis in Mumbai

contributed by Mariano Errichiello, 12 November 2020

With many European countries unfortunately experiencing a second outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is heartening to see that the situation in India is seeing improvement as the unrelenting rise of new positive cases since March of this year is finally slightly in decline. Given the ethnic and religious diversity of India, the implications of this pandemic are varied, presenting its many communities with their own unique challenges.

Around 40,000 Parsis live in Mumbai. They are the descendants of the Zoroastrians who fled to India after the Islamic conquest of Iran. Parsis settled in Gujarat and, from the 17th century, established themselves in Bombay, a place that was becoming one of the main business centres of India at that time. Being a key trade partner of the British, the Parsi community progressively gained social status and flourished into a wealthy and prestigious community.

Figure 1: Road sign in Dadar Parsi Colony, one of the largest Parsi colonies in Mumbai. (Photo credit: Mariano Errichiello, 2019)

The main distinctive element of the Parsi identity was, and still is, the Zoroastrian religion. Parsis have shown an unprecedented resilience in preserving their religion across the centuries and nowadays, they are considered those who have best retained the Zoroastrian ritual practices.

Figure 2: Entrance of the Rustom Framna Agiary, the Zoroastrian fire temple in Dadar Parsi Colony, Mumbai. (Photo credit: Mariano Errichiello, 2019)

Soul and body in the after-death ceremonies

According to the Zoroastrian beliefs, when a person dies, her/his soul advances towards the spiritual planes. As death represents the triumph of evil, the physical body becomes polluted. After-death ceremonies include the recitation of a set of prayers in order to aid the progression of the soul of the departed, as well as excarnation - which is the open-air exposure of the corpse to sunrays and to birds of prey (e.g. vultures). Since ancient times, Zoroastrians dispose of corpses in dokhmas, whose raised circular structure has suggested its English translation as the ‘Tower of Silence.’ In Mumbai, the Parsi dokhma is called by the Gujarati term Doongerwadi ‘Orchard on the Hill’ and was built exactly 350 years ago on an extended land of 55 acres in Malabar Hill.

Figure 3: Entrance of the Doongerwadi in Malabar Hill, Mumbai. (Photo credit: R. B., 2020)

Burial, cremation or dokhma? A long-standing issue for the Zoroastrians of India

Just like many other communal issues such as inter-marriage or conversions, there is heated debate among the Parsis about funerary practices. Where do these controversies come from? During colonial India, a progressive Westernisation process took place. Given their relationship with the British, Parsis became greatly exposed to their culture. Furthermore, Christian missionaries began to target Zoroastrianism in an attempt to convert Parsis. In this context, the religious vulnerability of the Parsi community was exposed and a reform movement to boost its legitimacy arose.

The reformers proposed a new interpretation of Zoroastrianism aiming at modernising the religion. This resulted in an increasing number of controversial issues within the community, some of which are still vehemently disputed today. During the recent years, there has been a relaxation of some religious practices: partly motivated by the vanishing of vultures’ population in Mumbai, a number of Parsis began to opt for cremation, considering this as a better option in changing times. However, a part of the community still fiercely opposes such ritual change.

The vast majority of the Parsi community maintains that burials pollute earth and that cremations contaminate fire. Earth and fire are considered sacred elements of creation and the rationale behind the use of the dokhma is to keep sacred natural elements pure by avoiding their direct contact with polluted corpses. Therefore, either the burial or cremation of corpses are to be considered heretical.

Figure 4: While reciting prayers before the sacred fire, Zoroastrian priests wear the padān, a cloth nose-mouth mask that prevents the saliva or breath to contaminate the purity of the fire. (Photo credit: Mariano Errichiello, 2019)

Cremation: Necessary ‘Evil’ or Unforgivable Heresy?

At the end of March, as part of measures to counteract the pandemic, the governmental authority of Mumbai informed the administrators of the Doongerwadi about the decision that all Covid-positive deceased persons must be cremated.

This restriction unleashed harsh protests from Parsis who take after-death ceremonies very seriously. The Trust that manages the Doongerwadi is the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP), which is the main government body of the Parsi community in Mumbai. Many Parsis were expecting their governing body to adopt an adversarial position in order to negotiate some kind of exemption for their community. Instead the BPP decided to assume a sympathetic position with the government of Mumbai, advising Parsis to follow the proposed measures.

As an accommodation, the prayers that are usually recited in the Doongerwadi are now performed at the prayer hall of the crematorium in Worli, in south Mumbai. However, Parsis who guard the authenticity of ritual performance actively scrutinise further potential initiatives in order to avoid setting precedents for any kind of liturgical innovation. On the 3rd of September, following a writ petition filed by the BPP, the Bombay High Court gave permission to perform the Farvardian ceremony in the Doongerwadi under the respect of social distancing norms. Considered as an important ceremony for Zoroastrians, the Farvardian consists of annual prayers to be recited in the Doongerwadi for those who have passed away during the last year.

Loss upon loss

As COVID-19 forces the world to adapt to new ways of conducting life and work, religious communities are also being forced to make concessions. Over the years, Zoroastrianism has been granted a somewhat privileged status in India, with relative freedom from interference by government authorities. However, it is clear that COVID-19 has no regard for the delicate balance once struck between state and religion. This pandemic has certainly changed the way Parsis mourn, in the case of COVID-19 victims; in addition, it has sown further division within the Zoroastrian community of India.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Mariano Errichiello is a PhD candidate at SOAS University of London. His research is on Ilme Kṣnum, an esoteric interpretation of Zoroastrianism introduced in the 20th century among the Parsis of India. His interests include Zoroastrianism and its related languages, esotericism, anthropology of religion and phenomenology of mystical experiences.

Other Interesting Topics

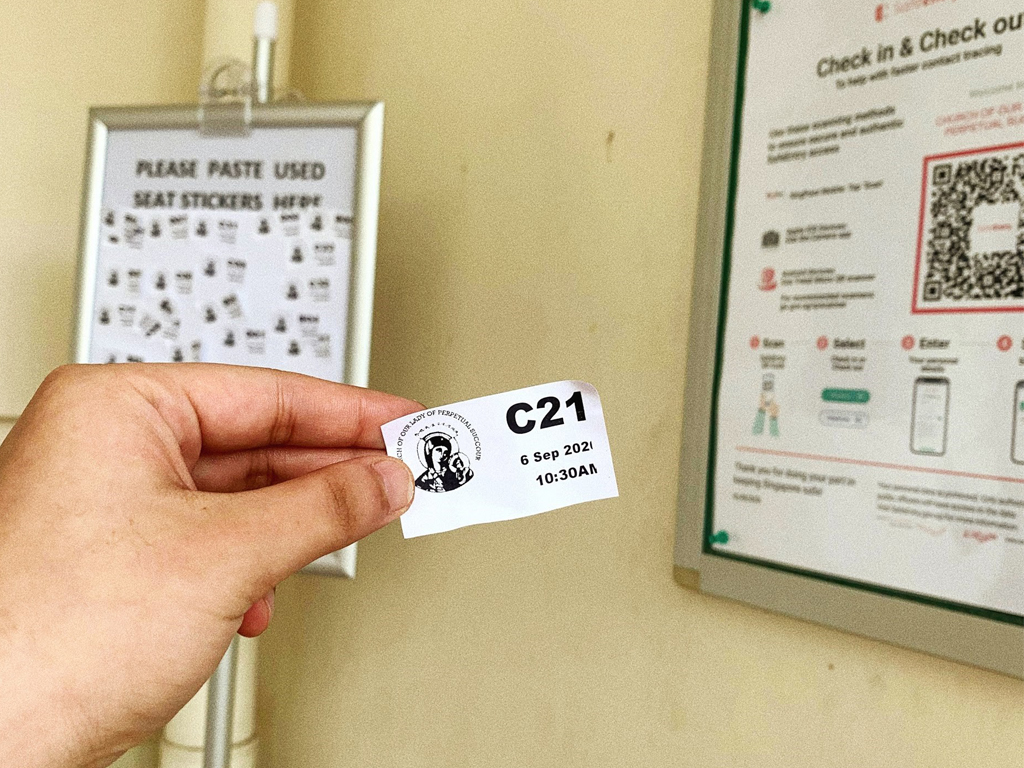

A Virus in the House of God: COVID-19 and Catholic Mass

On 19 June 2020, Phase Two of Singapore’s circuit breaker began. COVID-19 restrictions were eased, and religious gatherings up to 50 people were allowed. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore announced that Catholics could go to one weekend mass a month, starting from July...

Seeking Solidarity: Rethinking the Muslim Community in the Pandemic Era

Ramadan has just ended, and it has been a very unsettling one, to say the least. So many aspects of our religious lives, one that is very much to the idea of the community, have to be readjusted. Though, as some would put it, physical distancing does...