“Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray…(for) They will Understand:” (Part 1)

contributed by Esmond Soh, 7 January 2021

“Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray…(for) They will Understand:” Why was the Narrative of ‘Simplification’ Complex during the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in 2020? * (Part 1)

* An earlier draft of this essay had benefited greatly from the feedback provided by Asst. Professor Koh Keng We. The author is likewise grateful to the various Nine Emperor Gods temples – Jinshan Si, Zhun Ti Tang and Jiu Huang Gong – in Singapore for hosting his presence during the Festival in 2020. Any mistakes in this post are entirely his own.

Reposted with minor edits from: Soh, Esmond. 2020. “Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray…(for) They will Understand:” Why was the Narrative of ‘Simplification’ Complex during the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in 2020?” Nine Emperor Gods Project, December 10.

Figure 1. A makeshift inner altar (which conceals the invited Nine Emperor Gods from public view) in the Nanshan Hai Temple, Bedok Reservoir, Singapore. Photograph from the Nanshan Hai Temple Facebook page, 16 October 2020

Introduction

During the ninth lunar month, temples in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and other parts of Southeast Asia would celebrate the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods. Besides the inviting and sending-off ceremonies - both large-scale events in themselves - a steady stream of devotees would visit Festival sites during the nine days and more, with vegetarian food prepared for them during the Festival. The Festival had become the largest public religious celebrations for Chinese communities in much of western Southeast Asia, both in terms of its scale and duration. Yet, 2020 was to be very different with the proliferation of the COVID-19 virus.

I titled this essay with an offhand comment from a video posted by the Nanshan Hai Temple in the Bedok Reservoir region of Singapore, not out of sentiment or personal experience with the organisation, but in admiration of the speaker’s optimism amidst the poignancy of COVID-19 restrictions on crowds and religious gatherings in Singapore. This post, which focuses on the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in Singapore and Southeast Asia, provides an insight into the concerns that various temples hosting the Nine Emperor Gods’ worship had to negotiate and navigate with throughout this season. Among all else, I wish to problematise the consistent appeal to “simplification (简化/从简)” by the mass media which includes much more than the scaling down and/or outright cancellation of various rituals. Rather, the term also encompasses – paradoxically – a burgeoning body of measures taken to stem COVID-19’s spread as far as possible, which transformed the relationship shared by devotees vis-à-vis the occasion itself.

The ‘Simplification’ Narrative in the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods (2020)

Thoreau once noted that, “Simplify, simplify, simplify!” On the surface, organisers of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods this year were forced to take a leaf from Thoreau’s book out of concern for the safety and well-being of its devotees. As early as September 2020, the Malaysian Federation of Nine Emperor Gods Temples had encouraged temples to perform their receiving and sending-off ceremonies within temple complexes instead of going to the beach with an accompanying crowd. It is no exaggeration that at crucial rituals – be it from crossing the Bridge of Peace and Safety to the receiving/sending-off of the Nine Emperor Gods at the coast – crowds are the norm at temples that host the Festival. Clusters of devotees in close contact with one another were seen as potential sites of COVID-19’s transmission, and thus it was mandatory for precautions to be taken.

In other cases – particularly for temples that do not have sufficient space to erect a tentage for the occasion – the Festival had moved entirely within the constraints of the home. The Nanshan Hai temple described at the start of this blog was one such instance, as well as the Shen Xian Gong temple in Jurong West, Singapore. Although both temples typically used a neighbourhood basketball court and open field for the event respectively, circumstances this year meant that visits to these premises-within-homes were to be made on a staggered and restricted basis.

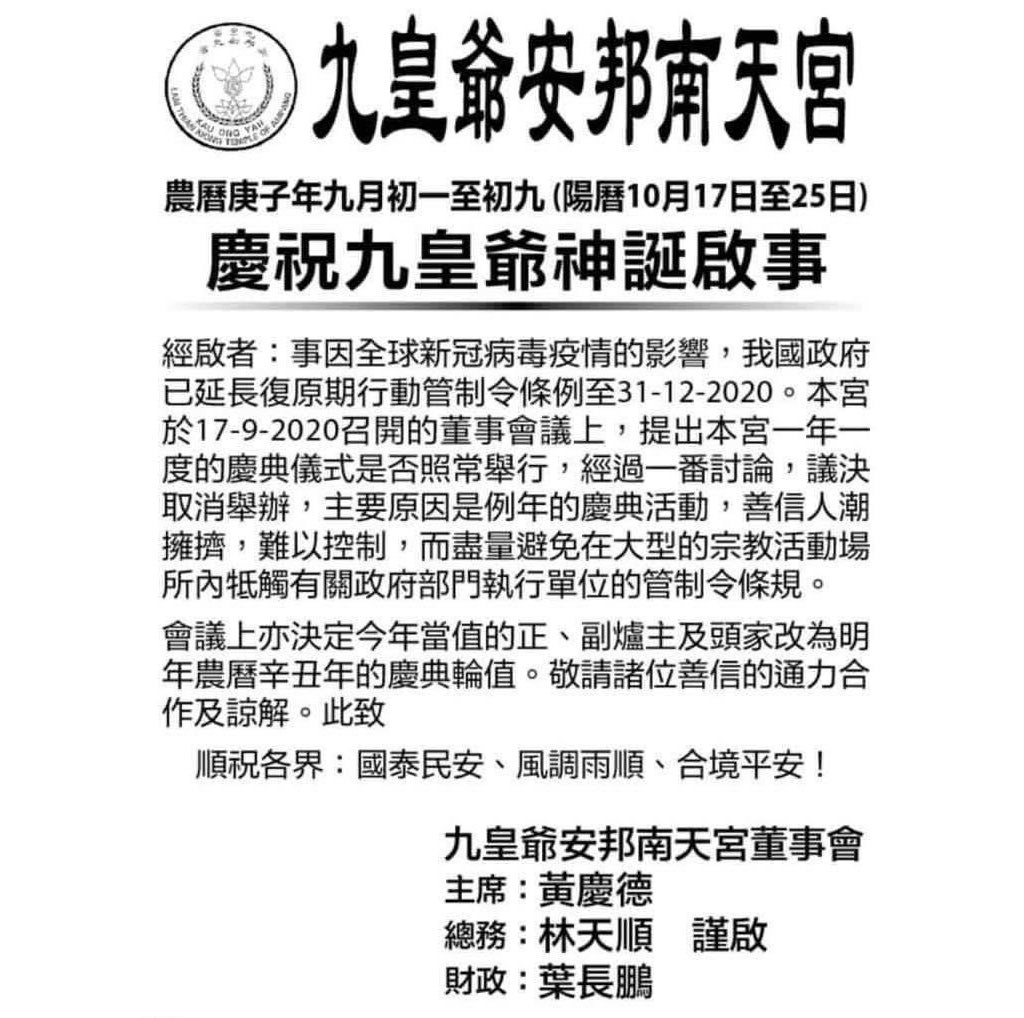

Simplification was also manifested in the form of cancellation and truncated activities, where temples had either removed certain rituals from their schedules or scrapped the event’s observation entirely. A key node among the network of temples which commemorated the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods, the Nan Tian Gong in Ampang, Kuala Lumpur was one such instance, where reports not only announced that the event would be cancelled this year, but also the responsibilities and titles of the censer-masters of 2020 would be carried over to 2021.

Figure 2. Announcement by the Nan Tian Gong Temple in Ampang declaring the cancellation of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, 23 September 2020. Wolfgang Franke and Chen Tieh Fan (1995) considered this temple to be one of the oldest and a centre for the Nine Emperor Gods’ worship in Malaysia

Elsewhere, other key rituals were likewise shortened or altered to fit incumbent constraints. The temple where I had undertaken fieldwork in 2019 – the Rumah Berhala Sam Siang Keng in Johor Bahru – comes to mind, where instead of going to the beach with a convoy of lorries, cars and motorcycles as in the past, an altar within the temple’s complex was set up to welcome and see the deities off. Likewise, although the Bei Hai Dou Mu Gong in Butterworth continued with the bulk of their activities with a thorough Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) presented through a pre-recorded video, supplementary rituals such as the ‘Nine Offerings’ were scrapped.

Figure 3. (Left) A procession of motorcycles and cars (the latter not pictured) followed the boat that would be used by Sam Siang Keng during the sending-off ceremony for the Nine Emperor Gods in Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Photograph by the author, 7 October 2019. (Right) Sending off the Nine Emperor Gods from a makeshift altar in the heart of the Sam Siang Keng Temple complex, Johor Bahru. Photograph from the Rumah Berhala Sam Siang Keng Facebook page, 25 October 2020

In Singapore, temples such as Zhun Ti Tang and Jiu Huang Dian that operated within smaller constraints were forced to modify rituals to meet the needs of their respective sites of operation. Previously, both temples had hosted the occasion from a large tentage. However, as of 2020, they were forced to operate and host the Festival within a smaller environment. Here, I wish to draw attention to the ritual known as the ‘raising of the nine lamps’, a practice that signals the temples’ observation of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods. In the past, a designated flagpole lashed with a stalk of bamboo would receive a pride of place outside of these two temples’ tentage. Given that both temples had opted not to erect a tentage for the said Festival in 2020, the flagpole cum bamboo mast had to be shortened and situated under a roofed premises instead of jutting into the skyline as it did in the past.

Figure 4. The Heavenly Lamps raised in Jiu Huang Dian, Singapore to mark the beginning of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in 2020. Note the bamboo pole (a key ritual implement) and the banner emblazoned with the title of the Nine Emperor Gods. Photograph from the Jiu Huang Dian Facebook page, 15 October 2020

Change, Continuity and Complexity during the Festival of 2020

Thus far, the ‘simplification’ of rituals would suggest that the Nine Emperor Gods Festival of 2020 lack authenticity, and the absence of crowds as well as the ‘hot and noisy’ renao (a key marker of aesthetic, emotional and psychological excitement at such events) festivities seem to imply that this year serves as a pale shadow in comparison to the years that preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. However, at an operations level, I think such a perspective does not do justice to the mental and physical acrobatics – both ritualistic and practical – undertaken by the organisers of the Festival, where they not only had to juggle with the day-to-day affairs of their temples, but also in consideration of restrictions related to COVID-19.

Figure 5. (left) Floorplan of one-way movement planned for the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods at Long Nan Dian, Singapore; (right) the waiting area prepared for devotees while they wait their turn. Photographs from the Long Nan Dian Facebook page, 17 October and 27 October 2020 respectively

Simply put, I contend that the discourse of ‘simplification’ or a ‘simplified’ festival conceals a dynamic and complicated body of rules, practices and efforts undertaken to ensure that the Festival continues to run as smoothly as possible. One does not need to look too far to see how logistics have transformed to match the scale of crowd control during this season: SafeEntry QR codes are prepared around temples, whereas for Long Nan Dian and the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong, a queueing system with a one-way entry was provided for devotees. I singled out these two temples not because other temples have neglected this dimension of crowd control, but to draw attention to how both organisations had noted the scale and age of their devotees’ demographic. Long Nan Dian, as we can see in figure 5 above, provided chairs spaced as per incumbent safe distancing rules, whereas a numbered-queuing station was set up behind the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong temple for devotees to register their particulars without clogging up key chokepoints within the combined temple complex.

Figure 6. Minister for Health Gan Kim Yong visits the queuing station and scans his SafeEntry QR code at the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong, Singapore. Photographs from the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong Facebook page, 19 October 2020

Moving religious festivities into cyberspace was one common solution to concerns over clustering and the en masse gathering of people. Livestreams of key ceremonies – such as the invitation and sending-off ceremonies – were conducted for the Hougang Dou Mu Gong and Feng Shan Gong, where for the previous, according to one estimate, reached out to at least 2000 viewers. The same also held true for the Pu Men Dian Dou Mu Gong in Malaysia: the poster, after admitting that he/she was not very fluent with social media, had “asked for the forgiveness of viewers if he/she had done anything wrong” before advertising the services and items that devotees can purchase online. The same goes for smaller temples in Singapore who abided strictly by the 50 pax rule during their invitation and sending-off ceremonies, such as the Jiu Huang Dian and the Nan Shan Hai temples.

Figure 7. Sending-off ceremony for the Nine Emperor Gods organised by Jiu Huang Dian. Note the one-meter spacing maintained between devotees. Photograph from the Jiu Huang Dian Facebook page, 26 October 2020

Cyberspace, Community and Camaraderie: What Counts for (and can be Omitted from) a ‘Simplified’ Religious Experience?

Yet, we should not run away with the idea that COVID-19 had marked a flawless transition from the physical to the virtual worlds. As I have noted elsewhere, the trek into cyberspace by Chinese religious organisations, while praiseworthy, remains uneven and privileges temples with the funding and resources available to rally a mass of dedicated photographers and videographers to their cause. The Hougang Dou Mu Gong and Feng Shan Gong as described have the privilege of being two of the oldest centers of the Nine Emperor Gods’ worship in Singapore. Bei Tian Gong in Malacca had also posted consistent updates about their worship ceremonies and programmes, a feat followed by temples in Phuket, where various shrines devoted to the worship of the Nine Emperor Gods maintained a steady stream of posts about the parades of their respective spirit-mediums.

Figure 8. Announcement cum cover photo of the sending-off ceremony (broadcasted live) performed by the Hougang Dou Mu Gong, Singapore. Photograph from the Hougang Dou Mu Gong Facebook page, 24 October 2020

At the other end of the spectrum, what about smaller temples that have fewer means of migrating their activities online? Although I am consulting an incomplete archive as of the time I am compiling this essay, from my preliminary findings, it is clear that the results are uneven at best. In contrast to the High Quality (HQ) official broadcasts by the Feng Shan Gong and Hougang Dou Mu Gong temples, other temples that have attempted a similar strategy have fewer resources at their disposal. The sending-off ceremony for the Jing Shui Gang Dou Mu Gong, for example, only included around half an hour’s worth of coverage. Smaller shrines and temples housed within homes – such as the Nan Shan Hai temple – posted consistent updates, but coverage like these pale out in terms of their length and media quality, given that they were taken and uploaded via smart phones. However, my point here is not to disparage the efforts of these temples who had attempted to balance their limited capacity of devotees cum visitors (we are again reminded that only 50 people are allowed to be a part of the core contingent charged with receiving and sending-off the Nine Emperor Gods), but to underscore the continued relevance of face-to-face participation and presence of the devotees involved, as I have argued elsewhere.

Figures 9, 10 and 11. Ringing a bell to welcome the Nine Emperor Gods into the temple; striking a drum continuously to mark the enshrinement of the Nine Emperor Gods in the temple’s inner-altar; and replenishing an incense censer with fresh sandalwood powder right after the Nine Emperor Gods were enshrined in the Jinshan Si Temple. Photographs by the author at the Jinshan Si Temple, Singapore, 15 October 2020

Moreover, the migration of religious activities into cyberspace detaches the viewer from a panoply of emotions, sights, smells and sounds that are neither easily ‘processed’ nor experienced through a screen. The scent of smouldering incense smoke, as well as gongs, bells and drums are all a part of the welcoming and sending-off procedures (alongside an air of solemnity that leaves no room for jokes or laughs when the moment is at hand), and I highly doubt that anyone who had participated in the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in-person would be able to enter a similar of state-of-mind while watching the proceedings in the comfort of their own home. In other words, we need to rethink the self-comforting and alluring – but inaccurate – narrative that the practice of religion can simply be moved into cyberspace during COVID-19. Devotes can be informed about what is happening by social media posts and livestreams, but to argue that they are also participating in the broadcasted activities seems to be a logical leap that I cannot uncritically accept.

Figure 12. (left) Bento-style vegetarian meals packed by the Bei Hai Dou Mu Gong in Butterworth, Malaysia, for distribution to devotees. The notice reads “Our temple will be providing three vegetable dishes and rice for our devotees. Given the pandemic, and for the sake of safety and takeaway purposes, we have chosen to use disposable boxes (to pack food). We welcome our devotees to collect a box from us at the following times…” Photograph from the Tow Boo Kong Temple Butterworth Facebook page, 17 October 2020. (right) Infographic posted to remind devotees at the Vegetarian Festival to prepare their own tiffin containers for takeaway. Photograph from the Kathu Shrine Facebook page, 14 October 2020

This also held true as far as food was concerned. A key marker of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods includes the sale and distribution of vegetarian food to devotees by temples that host the event, as Cheu Hock Tong had already described in detail for the case of Nan Tian Gong in Ampang. Given spatial, logistical and time constraints, many temples chose to forego this element of communal dining. With a more stringent protocol for food preparation licensing in a post COVID-19 world and also partially the need to ensure that devotees do not congregate together in dining halls, many temples have decided to omit this dimension of the festival this year. On the other hand, temples that continued to provide meals had taken special precautions that added to their workload: Bei Hai Dou Mu Gong in Penang, for example, offered a limited number of bento-style meals for takeaway during mealtimes, whereas the Dou Mu Gong in Sungei Dua and temples in Phuket insisted that their own devotees bring their own food and tiffin containers for food to be packed for takeaway.

As such, we can see how various temples strived to carry out the festival through their own means while working within the boundaries and restrictions implemented during the COVID-19 crisis. The second half of the post will continue to uncover how ‘simplification’ is interpreted in multiple ways, and yet not erase the very essence of the Nine Emperor Gods festival itself.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Soh Chuah Meng Esmond is a History graduate student enrolled in the Master of Arts program at the Nanyang Technological University, School of Humanities (SoH), Singapore. His research interests include the history of religion, diasporic Chinese religion and the history of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia.

Other Interesting Topics

“Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray… They will Understand:” (Part 2)

The role of ‘simplification’ in practice is also understood and manifested differently on many fronts. The same term – however applied – can be interpreted differently, and the examination of sacred time is instructive in this instance. Some temples chose to extend the operation hours

Moral and religious responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan

When the COVID-19 pandemic was rapidly spreading across the globe, Pakistan joined the global trend and declared a country-wide lockdown in mid-March. The lockdown inhibited major parts of the already struggling Pakistani economy from functioning in the typically uneven and unequal ways

Saint Corona, CoronAsur, and Corona Devi: New Embodiments

Saint, demon, and goddess – we seem to be at the mercy of Corona. The relation between religion and health probably dates back longer than both these terms exist, and pandemics have marked particular moments of this historical connection. Hagiographic accounts and oral narratives about divine forms from different parts of the world