“Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray…(for) They will Understand:” (Part 2)

contributed by Esmond Soh, 8 January 2021

“Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray…(for) They will Understand:” Why was the Narrative of ‘Simplification’ Complex during the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in 2020? * (Part 2)

* An earlier draft of this essay had benefited greatly from the feedback provided by Asst. Professor Koh Keng We. The author is likewise grateful to the various Nine Emperor Gods temples – Jinshan Si, Zhun Ti Tang and Jiu Huang Gong – in Singapore for hosting his presence during the Festival in 2020. Any mistakes in this post are entirely his own.

Reposted with minor edits from: Soh, Esmond. 2020. “Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray…(for) They will Understand:” Why was the Narrative of ‘Simplification’ Complex during the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in 2020?” Nine Emperor Gods Project, December 10.

The role of ‘simplification’ in practice is also understood and manifested differently on many fronts. The same term – however applied – can be interpreted differently, and the examination of sacred time is instructive in this instance. Some temples chose to extend the operation hours of their respective institutions in the hope that devotees could be better spaced out to prevent clustering. Long Shan Yan Dou Mu Gong and Long Nan Dian, for example, operated on a 24-hour model in the hope that devotees can come during off-peak hours and thus minimise instances of bottlenecking during the 11-day long event.

On the other hand, sacred time has been compressed in other instances in order to reduce the opportunity for intra-communal transmission. Sam Siang Keng in Johor Bahru, for instance, given that rituals that once lasted into the night were truncated, had their operating hours shortened to the typical opening hours of 0800 to 1700 hours daily. Likewise, Feng Shan Gong – despite having one of the earliest invitation dates for the Nine Emperor Gods in the previous years starting from the 24th day of the 8th lunar month in 2017 – had shifted the invitation ceremony to the 28th day of the eighth lunar month in 2020. Suffice to say, ‘simplification,’ although tossed around in the media’s characterisation of the situation this year, remains a vessel that is approached very differently by the leadership of various temples observing the Festival this year.

Figure 1. Miniature altar deployed by the Choa Chu Kang Dou Mu Gong to receive the Nine Emperor gods from the coast. Photograph from the Choa Chu Kang Facebook page, 17 October 2020. Also note how the invitation ceremony took place within an enclosed tentage (in the background) in the day, instead of the night as per previous years

Some temples who were forced to shrink their operations had tried to make the best of the situation by humorously suggesting that the smaller scale of worship meant that they had fewer things to worry about. On the other hand, it is precisely because of ‘simplification’ that new changes and rituals have to be developed on the spot to correspond with the unprecedented limitations imposed upon religious activities by COVID-19. This can be evidenced in the palanquins that are prominently featured in the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in almost all of the eighteen temples in Singapore which necessitated adaptation. As a result, temples who deployed palanquins this year had to create substitutes in the form of covered and portable altars that can be wielded by two bearers within a meter’s distance from one another.

Figure 2. Miniature altar deployed by the Nan Shan Hai Temple to receive the Nine Emperor Gods from the coast. Photograph from the Nanshan Hai Temple Facebook page, 17 October 2020

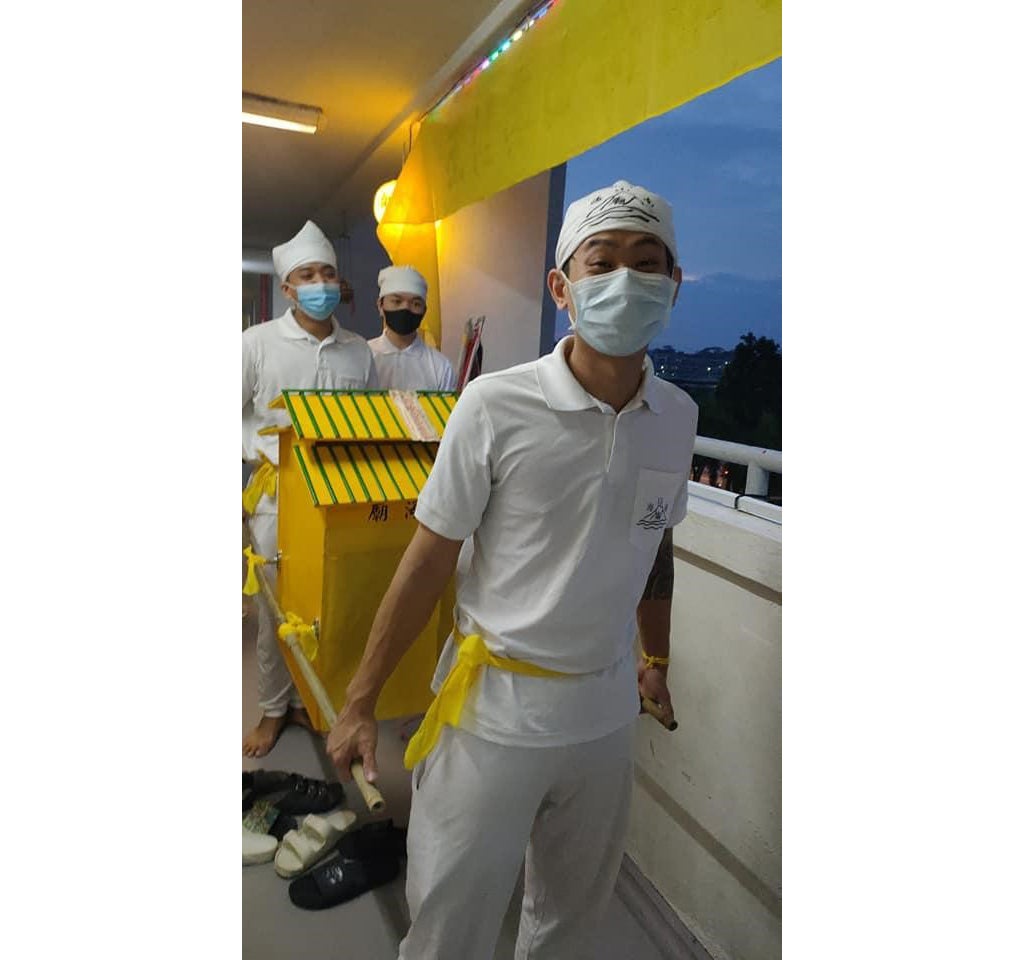

Alternatively, new ways of carrying these palanquins to maintain social distancing were adopted. For temples that chose to keep their palanquins of old, no longer were the palanquins allowed to sway, since such an action necessitated the close contact of two bearers at the front and end of each pole. Instead, the handles of these palanquins were now wrapped in yellow cloth and served to distance bearers from one another. ‘Simplification’ is thus much more than just striking key events and rituals from the schedule, but a complicated activity that demanded the ingenuity of temples to conceive of acceptable substitutions within the span of three weeks.

Figure 3. The handles attached to the palanquins from Jiu Huang Gong, Arumugam Road, Singapore were wrapped in yellow cloth, and were no longer carried around in a swaying motion by the palanquin bearers in 2020. Photograph by Louis Lim, Facebook photograph, 26 October 2020

I also argue that ‘simplification’ had presented both the devotees and organisers of the Festival with an opportunity to reform and rethink their operations in 2020 and (possibly) beyond as well. Given the growing number of devotees and temples that are participating in the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods, one wonders if this rethinking has also prompted a greater focus on the spirit of the Festival – namely “sanctity,” “purity,” and the discipline of keeping oneself morally and spiritually “clean.” Interestingly, this had already begun in some quarters even before COVID-19. Some time back, the Malaysian Federation of Nine Emperor Gods Temples had dissuaded the association of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods with Getai by emphasizing the need to focus more on the core values and spirit of the festival.

The restrictions on the scale and scope of activities for the Festival this year have nevertheless had a great impact on the broader ritual economy in Singapore and Southeast Asia. Elsewhere, Victor Yue argued that COVID-19 had hit catering and religious offering businesses as well as traditional arts and performances especially badly, and temples who worship the Nine Emperor Gods are now left to ponder about how best to buffer the next year’s budget without fund-raising banquets typically organised at the end of the festivities (see, for example, figure 4). A Chinese religious environment in a post-COVID-19 world, as tensions like this show, is one that attempts to balance the new with the time-tested rituals and traditions of old.

Figure 4. [Photograph was taken in 2019] The author’s table at a temple dinner hosted by Jiu Huang Gong, Singapore, at the end of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in 2019. Photograph by the author, 11 October 2019

Paradoxically, replacement, truncation and alteration can also translate into a form of elegance appreciated by devotees of old. The nine palanquins (one for each of the Nine Emperor Gods) deployed by Long Nan Dian every Festival come to mind, where they were replaced by lantern-esque parasol screens that sway gently in the wind. For myself – speaking as much as a researcher and a participant – and perhaps an aspect that I think is characteristic of the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods in all of its manifestations, is the continued presence of community. It is precisely in spite of COVID-19 times that festivals should be celebrated, for they re-forge old bonds and rejuvenate the institutions of old, be it from within families or a religious community (in another part of the globe, a similar case was made for Halloween’s continued observation in a post-COVID-19 world).

Figures 4 and 5. Parasol-esque sedan chairs prepared to transport the Nine Emperor Gods to-and-from the coast to Long Nan Dian, Jalan Kayu, Singapore. Contrast these sedan chairs with the four-men palanquins of old, the previous which only need two bearers. Photographs from the Long Nan Dian Facebook page, 26 and 27 October 2020 respectively

Let us not forget that temples also serve as key sites for senior citizens to interact and reconnect with one another, with the said demographic especially hard-hit by the Movement Control Orders (MCO) and Circuit Breaker (CB) measures enforced in Malaysia and Singapore respectively during the first half of 2020. Again, we do not need to look too far to affirm the communitas that the festival promotes: when I returned to Jiu Huang Gong in Arumugam on the sixth day of the ninth lunar month, the temple had continued to remain a center for the communal gathering of a Teochew enclave that used to live at the Lemongrass Village of old. Some signature rituals – namely the Nine Emperor Gods’ annual yew kampong tour into the heartlands of Singapore (figures 6 and 7) – which served to strengthen the bonds of this community with the temple, to be sure, had paused in 2020 given incumbent restrictions. Nevertheless, the continued participation of senior citizens and devotees in the temple’s activities is again testament to the resilience of the organisation as a communal institution. It is also buttressed by the appearance of an increasing number of younger devotees.

Figure 5. A senior devotee waits on his knees at the threshold of Jinshan Si with incense sticks in hand to receive the palanquin bearing the Nine Emperor Gods into the temple. Photograph by the author, 15 October 2020

Figures 6 and 7. [Photographs were taken in 2018] The Nine Emperor Gods from Jiu Huang Gong in Arumugam Road, Singapore, visited various different tentages erected by devotees to ‘welcome the Gods’ in the heartlands of Singapore during the yew kampong (‘tour of the village’) held on 14 October 2018. Most of these devotees (and their families) had originally hailed from a Teochew enclave located in the Lemongrass Village and Tai Seng areas until the villagers – and its associated temple – were relocated in the 1980s. Photographs by the author

Similarly, at Zhun Ti Tang, it was largely the devotee base from the old Sengkang neighbourhood estate that propped up the temple’s operations and activities. Parents and their children from the Rivervale and Sengkang east regions continue to feature in the temple’s volunteers. COVID-19 had changed many parts of the world, but the socio-cultural bedrock that underpinned the successes and operations of these temples have remained resilient, and while we should not take such continuities for granted, it is nevertheless a heartening experience and view for an otherwise volatile and uncertain post-COVID-19 world as of today.

On a penultimate note, I wish to draw attention to the role of private practice during the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods. Worship can refer to a diverse set of practices, and a “relational” means of worship that focuses on a religious institution’s engagement with the Nine Emperor Gods and/or community is only one out of many other possible modalities of “doing religion.” Although I have detailed many instances of communal observation, the personalised dimension of the Festival should not be discounted as well. Unlike the afore-mentioned instances, these largely-private instances of practice have continued with little or no change to the incumbent status quo. In some cases, they occurred precisely because of incumbent travel restrictions, as COVID-19 had grounded international travel to a halt since the first-quarter of 2020. Granted, some of these compromises have taken place because of incumbent restrictions, but we too should note that personal devotion and practice has – and will continue to – remain a part of the body of practices that give the festival meaning and significance.

Figure 9. (left) Presentation of food offerings to a spirit-tablet of the Nine Emperor Gods and the Matriarch of the Dipper in a private residence. Photograph by Jackson Tee Nirvana, Facebook photograph, 20 October 2020. (right) The author worshipping the Nine Emperor Gods at an altar installed in his own home. Photograph by the author, 13 October 2020

Conclusion: What does the Future Hold?

Without a doubt, COVID-19 is a crisis for the world as we know it, as familiar social, cultural and even political (both locally and abroad) routines were all reshaped by the restrictions imposed in order to stem the pandemics spread. Yet, despite the consistent harping and exaggeration about how Chinese religious festivals and rituals had to undergo a ‘simplification’ in order to survive and continue throughout these trying times, the reality – at least on the ground – is much more complicated than we had previously understood.

Some aspects continue fairly unabated, whereas other parts of the Festival – contrary to popular impressions of ‘simplification’ – involved creative manoeuvring within the span of a few weeks before and during the Festival itself. ‘Simplification,’ to borrow a common quip, is nothing more than an empty bottle that remains to be approached and filled by the many temples who are confronted with it. Under the narrative of ‘simplification’ belies a greater focus on the core values, rituals, and spirit of the festival. The need to reduce the scale and scope of events have led to a deeper soul-searching of what this festival is about, for the organizers and its devotees, viz. on its core and essential values, rituals, and spirit.

In other cases (as per cyber-religion), ‘simplification’ remains difficult to enforce in practice. More often than not, although live streams help to bring rituals to their devotees, the reality is that ‘ritual’ is in fact entangled with a panoply of emotions and sensations that cannot simply cross-over into cyberspace, even though many of us have taken conclusions like these for granted. Some institutions, such as community and ritual, continue to remain resilient despite the impact of COVID-19, and this trend (as I have consistently argued elsewhere) will continue to feature in the days to come. Yet, challenges – largely of a logistical and financial nature – continue to await Chinese religious institutions and their devotees in the horizon. How will the latter cope if the COVID-19 pandemic continues to last well into 2021? Only time will tell.

Soh Chuah Meng Esmond is a History graduate student enrolled in the Master of Arts program at the Nanyang Technological University, School of Humanities (SoH), Singapore. His research interests include the history of religion, diasporic Chinese religion and the history of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Other Interesting Topics

Soh Chuah Meng Esmond is a History graduate student enrolled in the Master of Arts program at the Nanyang Technological University, School of Humanities (SoH), Singapore. His research interests include the history of religion, diasporic Chinese religion and the history of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia.

Religious Televisuality in the Time of Pandemic

The Philippines is now on its sixth month of quarantine, hardly flattening the curve, no matter the spin of a government severely criticized for its politicking and misplaced priorities in the middle of the COVID-19 health crisis.

Re-envisioning the Ummah in the ‘New Normal’

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has undeniably been a watershed event in the 21st century. Much has been said about the various impacts of the pandemic, including the ways in which we organise and govern societies.

“Just Face the Nine Emperor Gods and Pray… They will Understand:” (Part 1)

During the ninth lunar month, temples in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and other parts of Southeast Asia would celebrate the Festival of the Nine Emperor Gods. Besides the inviting and sending-off ceremonies - both large-scale events in themselves - a steady stream of devotees would visit Festival sites