New Diseases, Old Deities: Revisiting Sitala Maa during COVID-19 Pandemic in Bengal

contributed by Deepsikha Dasgupta, 11 February 2021

The Goddess Sitala, or the ‘Cool One’(Wadley 1980), is worshipped by Hindus in Bengal and several parts of Northern India, as a controller of illness, protector of children, and bringer of good fortune. She is commonly associated with poxes, (primarily smallpox), malaria, any kind of fevers (jvar), infertility, and blood infections (Ferrari 2015). The rituals, myths, and practices surrounding the goddess are situated in the diverse corpus of alternative indigenous healing traditions in South Asia.

The pox afflicted patient is believed to have received the ‘grace’ of the mother goddess (Mayer daya). It is treated almost like an arrival of the goddess in the household. As her name suggests, she allays the feverish body with her coolness. Particular customs are prescribed for the small pox patient and the family. ‘Heating’ activity such as cooking or sex is prohibited in the household while water from tender coconuts, fenugreek water, and turmeric are either topically applied or orally prescribed (Arnold 1993).

Figure 1: The Sitala Temple at Dumdum, Kolkata (picture taken by author, January 2021)

For a goddess who wields command over illness and epidemics, how has the discourse about the goddess been informed with the outbreak of the pandemic? This essay, in its limited capacity, is an exploration of the religious imagination of devotees toward their goddess as it expands, absorbs, and adapts to changes in their practice of faith amidst COVID-19.

“I did not let the temple be closed”

Sheema, in her fifties, and a staunch devotee of the goddess, works as a helper to the priest at a local Sitala Temple in Dumdum, Kolkata. Referring to the nation-wide lockdown that was announced by the government to curb the COVID-19 pandemic in March, she describes how she argued with the police to keep the temple open. “I told them (the police) that if it were not for the goddess we would have perished”, she explains. The priest then went on to remind me, “why do you think the death toll in India is lesser than that of other countries?”

Figure 2: The Sitala Idol at the temple (picture taken by author, December 2020)

Seated on a platform with a broom and a pitcher in hand, the Goddess Sitala presides over disease and healing for all her believers in this busy street of the city. A devotee at the temple tells me that if a person has nobody to turn to in times of hardship, one is always welcome to weep at her feet. When asked about the pandemic, she adds, “Sitala is the medicine of all diseases; doctors can help us but the only way can be truly shown by Maa (mother).” Such unbroken immense faith in the goddess was reiterated by all of my interviewees.

With the easing of lockdown guidelines, the temple has now resumed having the usual visitors at the compound. A number of the visitors wear face masks complying with the government protocol while some do not wear them properly or not at all.

Lokkhi, a devotee in her fifties, lives within a few metres of the temple. She removes her own mask and shoes when she enters the garbha griha (sanctum sanctorum) of the temple. Shoes are traditionally taken off by Hindus when entering a temple or place of auspiciousness. It is ironic to see how the mask - a precaution against the coronavirus - is similarly coded into the realm of dirt and disease alongside shoes, and as such serves no use inside the temple as the goddess is believed to neutralize any virus in the air. Lokkhi quickly notices the mask and surgical cap on Sheema and questions the function of it inside the temple.

Sheema replies, “What if the virus finds a way in?”

Lokkhi points at the idol to say, “But who is sitting in the temple?”

For Sheema, she believes that the mask is still relevant and required to keep the virus at bay although she adds that at the end of the day, we are all at the mercy of Maa Sitala.

From above, we witness how the COVID-19 protocol, backed by biomedical understanding interacts with the religious responses of the devotees. Unlike general assumptions, it is not always in opposition (like for Lokkhi), but in conjunction (as in Sheema). It is evident in the way the vocabulary of biomedicine seeps into religious imaginations. Uttam, a forty five year old priest, performs the pujo at a village temple in Murshidabad, West Bengal, with whom I spoke to over the telephone. He explained how the gota sheddho (a vegetable dish) which Bengali Hindus consume on Sheetal shasti acts as a ‘vaccine’ to prevent pox in the spring. He believes that the ‘formula’ for the coronavirus vaccine can be found in the Hindu texts of Sashtras. He attributes the creation of the virus to man as he believes in the conspiracy theory of the virus having escaped from a laboratory. So one must pray to the goddess Sitala in order to destroy the ‘man-made’ virus and save the planet. In his opinion, the ‘new’ virus can be quelled by ‘old’ deities.

Figure 3: Gota Sheddho, image credits to experiencesofagastronomad

In some places of Bengal like Nichupara Basti, in Asansol, there were reports of worshipping Corona Mai - the Corona Goddess. Women sat in a field with flowers and incense to sing and chant mantras to ward off the virus. According to the women, the virus is a creation of the Goddess Sitala herself. Hence, they had gathered to pray to her, and a ‘new’ goddess, Corona Mai, until both goddesses were ‘satisfied’. As such, varied responses have manifested in the religious imagination of Sitala worshipers, which are not homogenous.

In an interesting unfolding of devi-asura (goddess-demon) dichotomy, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to the iconography of Corona Mai or Mata, as well as Coronasur (Corona demon) in Bengal. Several artisans from Kumartuli - the clay artists’ community of Kolkata - made Goddess Durga idols killing Coronasur where the demon Mahishashur (the buffalo demon) gets recasted and reinterpreted as a virus demon instead.

Figure 4: A durga idol depicting Coronasur (picture credits to The Times of India)

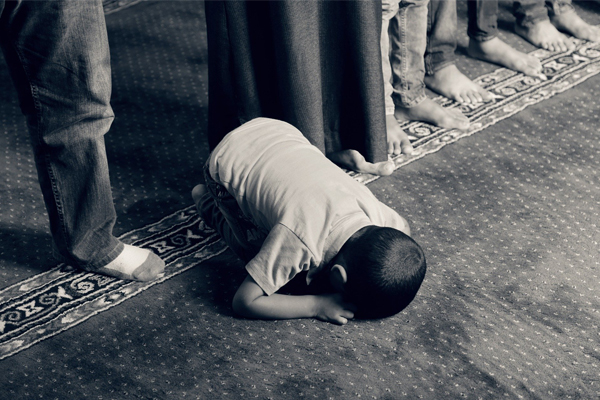

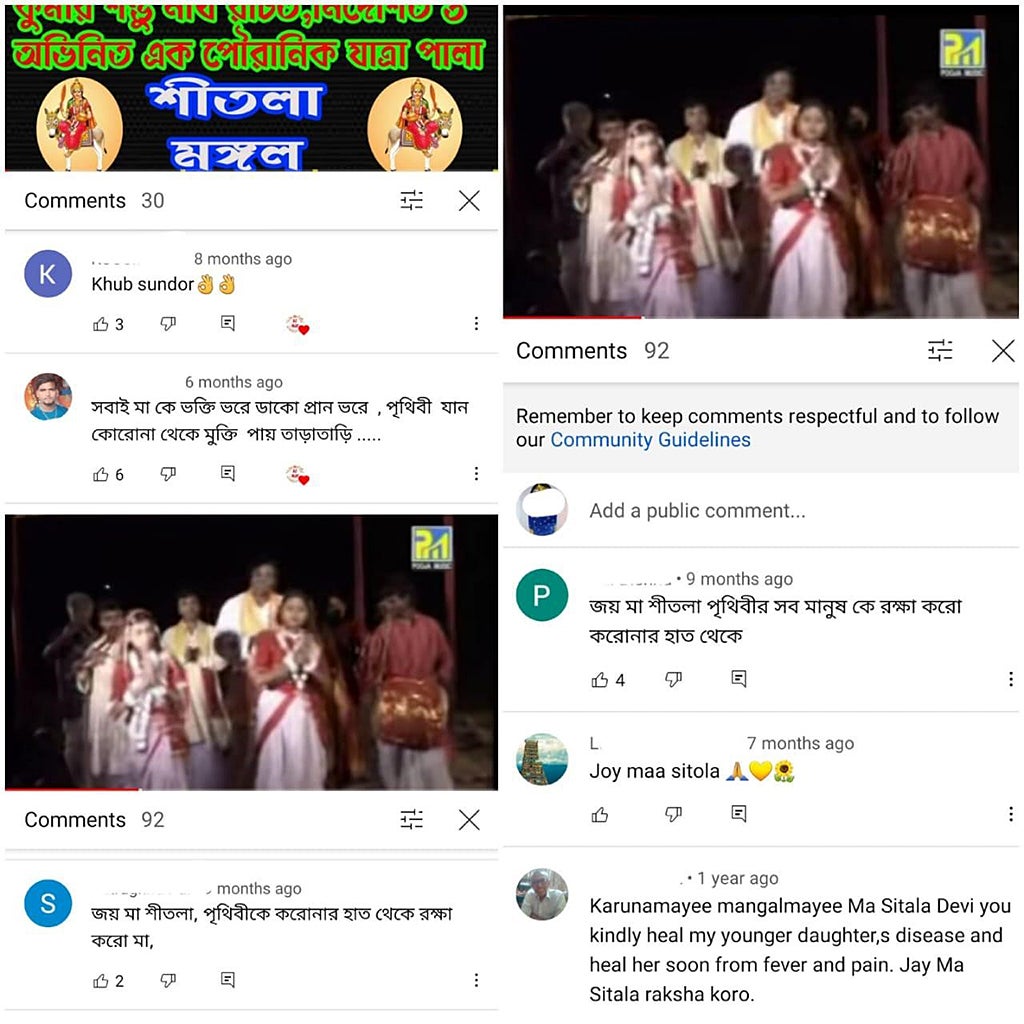

Digital spaces have opened up new ways for religious practices and interactions as physical distancing and lockdowns were enforced, as evidenced in the responses of Sitala devotees in the comment section on YouTube. There are a number of videos on the origin story, songs, and narratives surrounding the goddess from the Sitalamangalkabya. The poems and saga written in praise of mostly indigenous deities like Manasa, Dharma-Thakur, and Chandi comprise the Mangalkabya tradition. These deities are also known as nimnokoti (a rough translation would be ‘lower’) by historians due to their absence or lesser significant position among other divinities in the larger body of classical Hindu Vedic literature (Ghatak 2013). Nupur Dasgupta (2014) writes that the earliest Sitala Mangal was composed around the beginning of the seventeenth century and gradually the goddess was absorbed into the Mangal Kabya- Lokayata (popular) Mother Goddess category since the eighteenth century.

Figure 5: A collage of screen captures displaying the comments of Sitala devotees on YouTube

The public comments posted in the past eight months (since March 2020) often refer to the COVID-19 pandemic. A devotee appeals in the comment to collectively pray to the goddess as she alone can free the world of the virus. Comments were filled with praise for the goddess or prayers to the goddess. Even in the assurance and security of a vaccinated future, the faith in the ‘smallpox’ goddess arouses similar hopes for a post-pandemic world.

To conclude, a plurality of approaches and understandings converge and complement each other in the everyday life of Sitala devotees amidst the looming presence of the coronavirus. Through multiple interviews, observations, readings of newspaper reports, and a brief survey of online activities, I have attempted to explore these varied responses to and negotiations with the COVID-19 pandemic among the devotees of Goddess Sitala.

Works cited

Arnold, David. 1993. Colonizing the Body State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dasgupta, Nupur. 2014. “Environs and Cults: Tracing the Roots of the Social-Psychological Paradigm of Folk Existence in Deltaic Lower Bengal” Journal of Anthropology and Archaeology 2, no. 1:147-161.

Ferrari, Fabrizio M. 2015 “"Illness Is Nothing But Injustice": The Revolutionary Element in Bengali Folk Healing.” The Journal of American Folklore 128, no. 507: 46-64.

Ghatak, Proggya. 2013. “Continuity and Development in the Folk Tradition of Savaras of West Bengal: A Case Study of Sitala Worship” Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies 1, no. 1: 122-130.

Wadley, Susan S. 1980. “Śītalā: The Cool One.” Asian Folklore Studies 39, no. 1: 33-62.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Deepsikha Dasgupta is a final year BA student of Sociology at the Presidency University, Kolkata. Her research interests include religion, cultural studies, and gender. She is currently working on her undergraduate dissertation which explores the interface of COVID-19, biomedicine, alternative healing practices, and Sitala worship in Bengal.

Other Interesting Topics

Seeking Solidarity: Rethinking the Muslim Community in the Pandemic Era

Ramadan has just ended, and it has been a very unsettling one, to say the least. So many aspects of our religious lives, including the idea of the community, have to be readjusted. Though, as some would put it, physical distancing does or should not equate to social isolation.

Implications of COVID-19 on Ethno-Religious Tensions in Sri Lanka

Ethnic tensions have risen in recent years in Sri Lanka. Three key junctures represent new features. First came clashes between Sinhala Buddhist and Muslim communities in the south of the island in 2014.

Hospital ministry under coronavirus lockdown

My father, Gerry, is a veteran missionary for a small local Christian congregation in the Philippines that has held Sunday service at a hospital for the last fourteen years. Assisted by my mother Beth, he has done missionary work in various workplaces since the 1980s.