Cultural Heritage in East Asia’s Politics and International Relations

https://doi.10.25542/nnmz-ss25

Cultural heritage is deeply intertwined with politics. As it plays a crucial role in shaping a society's identity, values, and collective memory, no political actor, whether state or non-state, can afford to ignore the ‘power’ of heritage. With George Orwell’s famous quote from 1984, "Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past” in mind, the ways in which cultural heritage is at the center of power struggles, including the ways in which societies come to be ordered in certain ways, remains an important domain of scholarship.

Conventionally, the use of cultural heritage has been discussed mostly in relation to domestic, national contexts. First and foremost, cultural heritage serves as a vital tool for nation-building, particularly evident in the case of relatively young nations lacking a cohesive historical and cultural foundation. A noteworthy example is Singapore, where the government strategically employed cultural heritage to forge a shared memory, often emphasizing the shared experience under the Japanese occupation of Singapore. This deliberate effort to foster unity occurs within a society characterised by racial and cultural distinctions.

Even in nations with a more homogeneous cultural fabric, the ongoing challenges posed by globalization and diversification warrant sustained initiatives to cultivate a national sense of cohesion. The potential disruptions to a collective national identity underscore the importance of consistently reinforcing a shared cultural heritage.

As we know, cultural heritage also serves as a powerful tool for nation branding. Heritage sites, monuments, landscape, oral traditions, and cultural practices have been shown by numerous scholars to be symbolic representations of a people's historical legacy. These elements encapsulate and are made to speak of ‘values’ and ‘traditions’ spanning decades and centuries, making them invaluable resources for shaping national images, albeit potentially reinforcing certain stereotypes—be they exotic, unique, or universal. The inclination toward promoting nation branding is often observed in states driven by political or commercial interests. Some take pride in garnering international recognition for their heritage, while others are primarily motivated by economic considerations, such as the promotion of tourism to enhance their economic gains.

Heritage conflicts in East Asia

Similar to any potent resource, cultural heritage, if wielded without careful consideration, has the potential to lead to unintended conflicts or exacerbate existing ones. Over the past decade, East Asia has witnessed such heritage-related disputes, particularly pertaining to the remembrance of World War II.

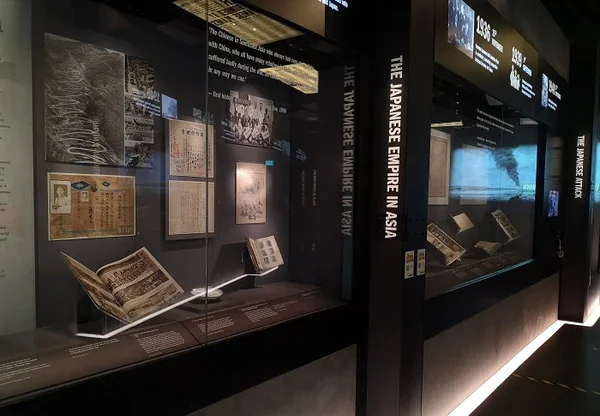

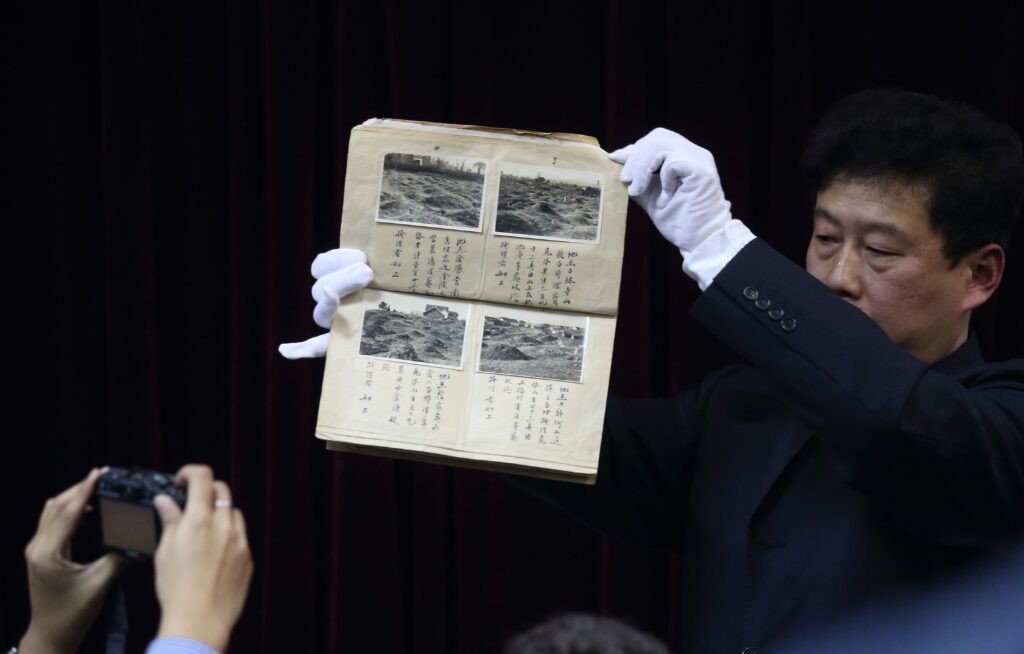

Within UNESCO, conflicts have arisen surrounding WWII-related heritage. One instance is the inclusion of the Document of Nanjing Massacre, nominated by Chinese archives and museums, in the Memory of the World register in 2015. This decision sparked vehement objections from Japan, characterizing it as a "unilateral" move to include a controversial document.

Similarly, the inscription of the Sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution on the World Heritage list in 2015, resulted in complex diplomatic negotiations between Japan and South Korea. As part of the agreement, Japan was expected to provide information on forced labor as a crucial aspect of the history associated with one of the sites, Hashima or the Battleship Island. However, Japan's failure to fulfill this commitment led to a protracted conflict between the two countries.

The conflicts in question have adversely affected UNESCO's reputation and highlighted its limited capacity to mediate disputes. Given Japan's prominent role as the second largest financial contributor to UNESCO, the organization found itself constrained by Japan's proposal for restructuring the Memory of the World (MoW) program. This restructuring was primarily aligned with Japan's interests, aiming to thwart the assessment of the Voices of Comfort Women, a nomination put forth by a Korean-led transnational civil society group.

Following a "comprehensive review" conducted by the MoW Secretariat from 2018 to 2021, significant changes were implemented to enhance the UNESCO Executive Board's influence in the selection process. Critics have expressed concerns that these modifications may inadvertently foster self-censorship, as they potentially prioritize political considerations over objective judgment. This transformation, driven by the dynamics of financial contributions and geopolitical interests, underscores the challenges UNESCO faces in maintaining impartiality and promoting the preservation of cultural heritage without succumbing to external pressures. The controversy over the Battleship island also made it clear that the great ideal of the World Heritage, that is, to protect the heritage for humanity, can easily fail.

Reimagining the world through cultural heritage

In contrast to the promotion of cultural heritage tied to national legacy, the advocacy for transnational cultural heritage appears benevolent, highlighting a shared memory that transcends state borders. This emphasis on shared history has led UNESCO to actively champion the preservation of Silk Roads heritage, with state backing for the Silk Roads conservation project viewed positively as a form of international cooperation. Nevertheless, there remains a degree of skepticism, as a broader transnational vision may also be perceived as serving the expansionist interests of emerging powers.

With the contemporary international landscape dominated by a shift in power dynamics, the way emerging powers interpret and redefine international relations has become a focal point. Notably, China has garnered significant attention for its multifaceted endeavors aimed at challenging established institutional frameworks. The Belt and Road Initiative, in particular, is perceived as a formidable challenge to the existing international economic assistance regime. China has marshaled diverse resources to fortify the Silk Roads heritage, underscoring its commitment to connectivity. The sheer magnitude of implementation goes beyond merely establishing a single memory institution; instead, it shapes a "memory infrastructure" reminiscent of socio-economic frameworks that underpin people's behaviors and activities. The network of memory institutions, constituting memory infrastructures, forms the bedrock for the retention and forgetting processes, contributing to the durability and persistence of collective memories. This intricate process encompasses not only elites or epistemic communities but also involves ordinary citizens and international tourists who engage with historical sites to glean insights into the past. The construction of the Silk Roads heritage, geared towards popularizing China's geopolitical vision, reflects a strategic interest in ensuring that this heritage is embraced widely by people beyond its borders.

It comes as no surprise that concerning voices emerge out of the areas surrounding China’s. For those who recognize the pivotal role of history in shaping collective identity, the dominance of one's history by another nation's narrative is deeply troubling. This concern became particularly pronounced when China nominated the ruins of the Koguryo kingdom as a World Heritage site, sparking a controversy that alarmed Korean historians who feared the potential erasure of a core part of Korean national history. Because the Silk Roads are not attached to one specific country, the revival of the Silk Roads heritage may not create a conflict with such intensity. However, there remains a lingering apprehension among historians and heritage experts in Japan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia that the incorporation of Silk Roads stories into a Sinocentric historical narrative could lead to the marginalization of their own historical legacies. While cultural heritage in itself may neither cause harm nor instigate change, it cannot be detached from the broader framework of constructing the world order. This interconnection holds the potential for a lasting impact on the legitimacy of China's envisioned order.

To return to Orwell, one could argue that the manipulation of historical memory is intrinsic to political discourse. Cultural heritage, as a byproduct of the political realm, works through and extends outwards from traditional political arenas such as parliaments, formal diplomacy, and public spaces. The political, in its broader sense, is interwoven into the fabric of everyday activities that shape societal structures where politics unfold. Consequently, cultural heritage becomes a potent tool for long-term influence over collective consciousness, warranting careful attention, especially amidst the complexities of East Asia’s politics and international relations.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.