Culture, Education and Literature: How are the Chinese faring in Brunei Darussalam?

https://doi.org/10.25542/820c-k125

As one of the top three largest diaspora in the world, ethnic Chinese have a visible demographic presence in Southeast Asia. With China’s rising global power through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the visibility of mainland Chinese has expanded rapidly in this region. In the nation-state of Brunei Darussalam, ethnic Chinese comprise 9.5 per cent of the total population of 445,400. Transient migrant workers from mainland China who stay fewer than six months are very likely not reflected in the ethnic Chinese segment of the national population census. Distinguished from local Chinese who have lived in the country for many generations, the recent arrivals from mainland China are due to foreign direct investments, such as the Hengyi Industries oil refinery constructed within a 955-hectare industrial park in Pulau Muara Besar in Brunei Bay. By contrast, local Chinese may have come either from mainland China many decades ago as part of the migration fever to Southeast Asia or arrived from Brunei’s neighbouring countries, Malaysia and Indonesia, to work and raise their children in Brunei Darussalam.

As an oil-rich state, Brunei Darussalam offers free education, medical services, and housing to its citizens. Subsidies in both healthcare and education are also available to permanent residents (PR). Despite being born and raised in Brunei Darussalam, some become stateless PRs by law because their fathers were not Bruneian citizens at birth. The stateless status of ethnic minorities, such as the Chinese and the Ibans, makes it difficult for them to access rights and privileges that are reserved for those with citizenship. As the stateless hold certificates of identity rather than passports, international travel can also prove challenging. Applications for nationality tests remain open and available to PRs who desire citizenship. As of July 2023, at least three citizenship-granting ceremonies have been held with thousands of people, including local Chinese, receiving Bruneian citizenship. This uptrend is promising, as the citizenship process is typically lengthy, with applicants having to wait a number of years to be eligible for citizenship.

In Brunei Darussalam, local Chinese have assimilated to various extents in terms of culture and education. Since its independence in 1984, the nation has upheld the ideology of Melayu Islam Beraja (MIB, Malay Muslim Monarchy). With economic and cultural processes of localisation gaining momentum after national independence, local Chinese have also participated in this national endeavour. By taking on government roles and private sector jobs, they contribute to the national economy. Muslim converts among Chinese Bruneians are also not uncommon in this Syariah-compliant nation. Local Chinese may attend state schools that are free for citizens and heavily subsidised for permanent residents, while others opt for private schools, including Chinese schools established by the Tiong Hwa community that offer a Chinese language education.

Regardless of their citizenship status, local Chinese contribute actively to the national community. Formal organisations such as the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, which was established after the Second World War, play an integral role in nation building by supporting local Chinese entrepreneurial activities and their bilateral ties with the Malay Chamber of Commerce. Sociocultural practices organised by Chinese cultural associations play a fundamental role in transmitting Chinese culture and identity across different generations. Moreover, the Teng Yun Temple (loosely translated as the Temple of Flying Clouds), located in the capital city of Bandar Seri Begawan, continues to serve as a place for ancestral worship, Chinese rituals, and annual Chinese festivities. Every Lunar New Year, cultural performances such as lion dances are performed for children and grand/parents, as well as residents and tourists in the nation.

As a matter of social duty, education is another major area in which local Chinese are heavily invested. The Chinese diaspora in Brunei have established several schools, most notably the Chung Hwa Middle School (CHMS), which was founded by Pehin Kapitan Kornia Diraja Ong Boon Pang after the First World War. It was formerly referred to as Yik Chye School. The Chairman of the CHMS Board of Directors contributed to the building of a pedestrian bridge, which was opened in 2015, to facilitate the crossing of a busy interchange by students and parents as well as the ferrying of children in and out of this school located in the capital. Quality educational services have led to consistent student enrollments among the Chinese and non-Chinese population, for whom Chinese middle schools carry a considerable reputation as high-achieving educational institutions. These Chinese schools also offer a third language of Mandarin for non-Chinese students, which supplements the official Malay and the widely spoken English language offered in both state and private schools across Brunei Darussalam.

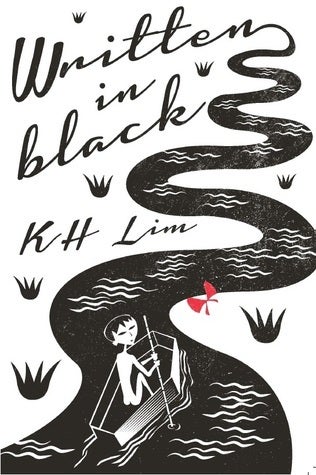

In the cultural arts scene, local Chinese have been active participants in literary writings and the performing arts. In fact, they have contributed to a nascent Anglophone literary scene with their novels, poems, and plays that are informed by their Chinese diasporic background. Through the fictional form, their literary texts offer insights into their Chinese roots and culture. For instance, K. H. Lim’s Written in Black (2013) is a novel that deals extensively with Chinese identity in Brunei Darussalam through its delineation of Chinese cultural rites and familial dynamics within the physical and social settings of Brunei. Additionally, poems by the Chinese Bruneian Andy Sia tap into various elements of Chinese heritage and reach an international audience online.

The local reception of poems and plays written by Chinese women in Brunei Darussalam also signals an encouraging outlook for the ethnic Chinese to participate in the local literary arts scene. To illustrate, May Cho’s coming-of-age play entitled Tomorrow, the Sun Sets (2022) was staged for a domestic audience at the Black Box Studio in Brunei Darussalam in the past year. Although small, there was a sizeable turnout of multiethnic theatre-goers consisting of local Chinese and Malays, who showed both a keen interest in local performing arts and an enthusiasm in a production written from the margins of society. With their valuable stories, local Chinese writers offer many generations of Bruneians insights into specific histories and identities via an accessible medium that is layered with imaginative possibilities. Such performances offer entertainment, but are also appreciated for their social commentaries. Even though Anglophone Chinese Bruneian literary works may not deal directly with the challenging issue of statelessness, the theme of generational loss that alludes to familial histories spanning the social and political changes of Brunei Darussalam from a British protectorate state to a Malay Islamic Monarchic nation-state comes achingly close.

Anglophone literary works by Chinese Bruneians, foreground the theme of mental health while navigating intergenerational relationships in the family and nation. Mental health has been raised as a public agenda in Brunei Darussalam under the Mental Health Order 2014 and the Mental Health Action Plan 2022-2025. In Written in Black, ancestral ghosts and haunting are symptomatic of physical absences and feelings of loss experienced by the local Chinese characters. In this Bruneian novel, the demands of cultural assimilation in the nation unfold alongside social dynamics in the Chinese family, raising the issue of mental stress or ill-health stemming from such exigencies. Anxiety and depression are interwoven into the characterisation of Chinese children and their grand/parents amid familial, social, and affective challenges. Nevertheless, the resilience of the Chinese over time and generations is apparent in the optimistic tone evident at the conclusion of this literary work.

As literary writings narrate culture and identity in the family as well as the nation, the educational value of these stories transcends current generations living in the present day. Even as literature written by the Chinese diaspora cannot accrue significant economic gains for the writers, these stories play an important role in the cultural transmission of tangible and intangible cultures across generations within the nation and region. Notwithstanding their international accessibility, the demand, market, and production of Anglophone Chinese Bruneian literature remain modest. In this respect, the Chinese diaspora to Brunei Darussalam shares similarities with Chinese minorities who live in neighbouring Malay-Muslim dominant nations of Malaysia and Indonesia. Nevertheless, Brunei Darussalam’s welfare and tax-free policies mark their unique life experiences within a politically and socially harmonious nation that is also referred to as the “Abode of Peace”.

While they remain marginalised from the Malay dominant group in Brunei Darussalam, local Chinese continue to vocalise their everyday experiences, social challenges, and affective struggles through their emergent literary writings. Apart from new literary writings in English, Sinophone literature by the Chinese Bruneians have also been around and for much longer. Although it is a small and ageing community, the Bruneian Chinese Writers Association (汶萊作家協會) has produced works that articulate both the pleasures and predicaments of everyday life in the nation. Their literary writings traverse double-edged portrayals of romanticising life in a peaceful and tropical paradise on one hand, and describing their helpless stateless predicament on the other.

Overall, the future prospects of the ethnic Chinese in Brunei Darussalam remain positive as they navigate not just the national sphere, but also interregional and intraregional networks within Southeast Asia. Stability and peace are enjoyed through political and social harmony in the nation, which has enabled their businesses and other endeavours to thrive. As diasporic subjects, they have a rich and expansive transnational network at their disposal. As Brunei Darussalam mediates the ongoing demands of localisation and globalisation, the local Chinese in Brunei look set to continue contributing to national and regional developments through their culture, education, and literature.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Hannah M. Y. Ho is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the Universiti Brunei Darussalam. She is also a National University of Singapore Fellow (Southeast Asia). She is engaged in research in the Inter-Asia Engagement Research Cluster at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore and is the principal investigator (PI) for funded research projects on “Representations of the Chinese diaspora in Brunei Darussalam” and “Mental Health Representations in Brunei Darussalam and Malaysia”. Her forthcoming articles are to be published in Kritika Kultura and Suvannabhumi. She is currently working on a volume entitled Transnational Southeast Asia: Challenges, Cultures and Identities (Springer).