Dokkaebi and gumiho: Reimagining masculinity and geopolitics in Anthropocene Northeast Asia

Lee Yeon spends time with his tiger friend in the mountains.

A still from Tale of the Nine Tailed (2020), episode 2, streamed on Netflix.

Gender, geology, and Anthropocene geopolitics

Supernatural and multispecies elements from two K-dramas, (1) Tale of the Nine Tailed (2020) and (2) Guardian: The Lonely and Great God (2016), are intriguing. Both male leads, Kim Shin (a goblin; tokkaebi) and Lee Yeon (a nine-tailed fox; gumiho), are constitutionally connected to, and often communicate with, animals and geological features such as butterflies, forests, fireflies, the moon, and the rain. Additionally, Kim Shin and Lee Yeon are both fighting malignant spirits that not only threaten their loved ones but also have been lingering and bringing harm to human communities and native deities.

Concerning Guardian: The Lonely and Great God, two culture reporters for Korea.net have offered their commentaries in a dialogic piece. Reporter Yostina wrote: “I’m guessing that the most important reason for me is that it’s charged with emotion, specifically vulnerable male emotions.” Reporter Lalien wrote: “I’m not really sure what makes it a big hit. Is it the story? This kind of story has never been told before on Korean television.” Concerning Tale of the Nine Tailed, director Kang Shin Hyo revealed quite explicitly an intention to bring a folkloric masculinity into the alternative spatial constructions in contemporary East Asia: “What would it be like if a guhimo was living in modern times? […] What sets our drama apart is that the gumiho are male, they are living in the modern age, and they are waiting for a long-lost love.” Here, the themes of gender, geopolitics, and the Anthropocene come together in a way worth further exploration.

The Anthropocene denotes the proposed current geological epoch on planet Earth where human activities have become a dominant geological force, directly impacting the ecological, chemical, and climactic features of Earth’s biosphere, marine and terrestrial. In official terms, the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) under the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) has, in 2024, rejected by vote the proposal by the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) (under the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy) to include the Anthropocene as a new epochal unit in the Geologic Time Scale. But the official IUGS statement also supports and encourages the continued reference to the Anthropocene: “the Anthropocene as a concept will continue to be widely used not only by Earth and environmental scientists, but also by social scientists, politicians and economists, as well as by the public at large. As such, it will remain an invaluable descriptor in human-environment interactions.”

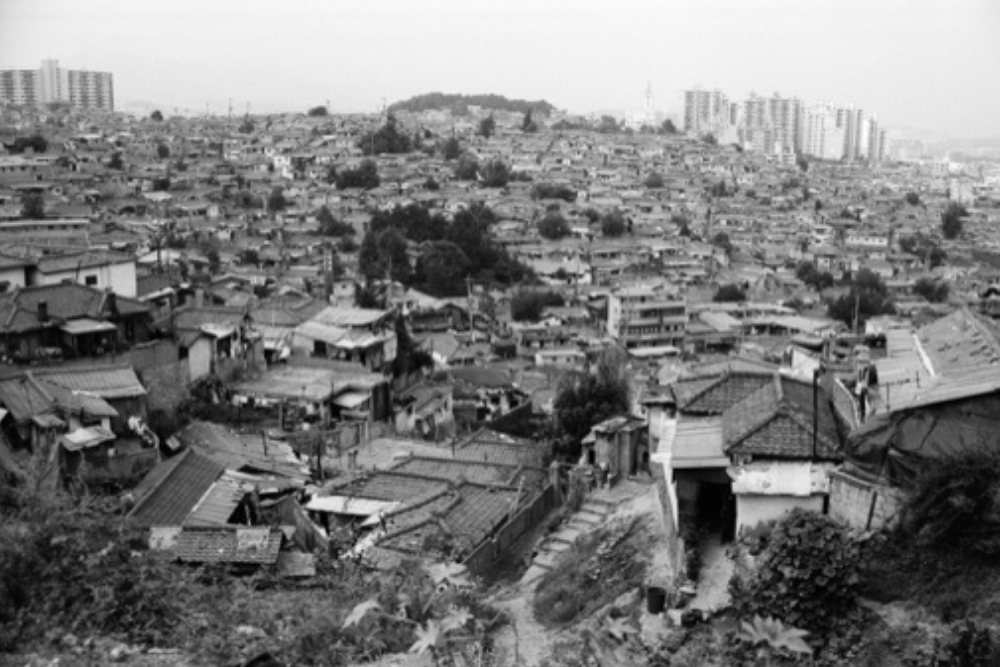

Geologists and anthropologists have been looking for ‘responses’ to the Anthropocene, to resist the planetary anthropogenic environmental and ecological devastations. Anna Tsing’s (2016) seminal article on the Anthropocene, ‘Earth Stalked by Man’, introduces a feminist anthropological approach to the Anthropocene. There are two key bases. First, the cause of the Anthropocene cannot be detached from European colonialism and industrialisation (e.g. the start of burning fossil fuels, advent of steam engines), rapid North American industrialisation after World War II (i.e. Fordist mass production and replication), and their contemporary perpetuations and differentiations across the various regions and subregions. Second, these global anthropocentric power systems were rooted in the European ideology of the ‘Enlightenment Man’ that separates human rationality from Nature. For Tsing, the Anthropocene is when Nature finally reminds Man of His limits: “Anthropocene refuses the heroism of Man’s struggle against his great antagonist Nature and reveals the terrors of His planet-wide destruction” (2016: 3).

In fact, scholars have been looking at East Asian spiritual cultures to address the Anthropocene. Animist (‘eco-spiritual’) traditions from Northeast and Southeast Asia have been a recurrent mention in related works, such as Mark J. Hudson’s (2014) ‘Placing Asia in the Anthropocene’ and Dahlia Simangan’s (2019) ‘Situating the Asia Pacific in the Age of the Anthropocene’. Geologists have also alluded to animistic practice: “will [humanity] have the humility (and good sense) to pull away from its present cause, redefine its relationship with the rest of nature”?

Tokkaebi, gumiho, and the malevolent spirits

Studies of K-pop, K-drama, and Korean cinema have often identified infantilised (boyish, innocent), flowery, and ‘soft’ forms of gentrified men. Indeed, research into South Korea screen cultures remains heavily centred on a ‘soft masculinity’ as part of the country’s soft power outreach. Soft men are a dominant South Korean reconstruction of gentrified men: rich men, but ones that are also well-behaved, beautiful, and boyish. These soft men often appear in dramas portraying chaebol organisations, namely the family-owned business conglomerates that have dominated South Korea’s modern economic development.

While the male leads in (1) Guardian: The Lonely and Great God and (2) Tale of the Nine-Tailed are also adorned with features of Korean soft masculinity (e.g. beautiful fashionable appearances with innocent and respectful demeanours), their ethical processes, as well as their peacebuilding tasks in late modern Korea, reveal less explored and less documented geopolitical elements.

In Guardian, the main male character is Kim Shin. This character’s entire existence is a struggle with fate and memory. From the Goryeo Dynasty, Kim Shin is a military general, loyal and faithful to the Goryeo king. But the young king (Wang Yeo), misled by corrupt officials, misunderstands Kim Shin as a threat to the throne, and thus, orders the execution of Kim Shin. In the process, the king also kills Kim Shin’s sister, Kim Sun, who is actually the queen (i.e. Wang Yeo’s own wife), and who does not waver to resist the royal edict to protect her brother.

The Gods intend to resolve this ill fate the right way. They resurrect Kim Shin in the form of an immortal demi-God: a goblin (dokkaebi). Kim Shin, now a dokkaebi, is only allowed to rest in peace if he sorts out the bad fate with Wang Yeo, Kim Sun, and all the corrupt officials manipulating the Goryeo monarchy. The Gods pierce a sword through Kim Shin’s heart, and only his destined bride, Ji Eun Tak, can see and remove this sword. This sword is destined to be used for destroying a corrupt Goryeo official’s lingering evil spirit, upon which Kim Shin can finally move on. For nine hundred years, Kim Shin has been waiting for his bride, unable to die and move on, all while bringing miracles to people’s lives, such as by creating hope amongst struggling families and children.

Kim Shin is worried for his missing bride (Ji Eun Tak, who does not want to remove the sword on his body, because it will also end his life). His emotion calls up a ‘supermoon’ to communicate his concern. Meanwhile, God is telling Kim Shin: “Remove that sword immediately.”

A still from Guardian: The Lonely and Great God (2016), episode 9, streamed on Netflix.

In Tale of the Nine-Tailed, the main male character is Lee Yeon. This character’s entire existence is a struggle against a powerful evil serpent (imugi, from Korean folklore). From premodern Korea, Lee Yeon has been chosen to serve as a mountain guardian: a nine-tailed fox (gumiho) with supernatural powers. Soon after, the serpent, imugi, feels resentful and intends to take his place, and attempts to do so by possessing the body of Ah Eum, a woman whom Lee Yeon loves.

Ah Eum, knowing her body is possessed by evil, sacrificed her life to bring down the imugi. The story then follows Lee Yeon’s emotional and ethical journeys: to look for Ah Eum upon her reincarnation as Nam Ji Ah, to protect all human and non-human beings against evil spirits, and to fight against the resurrected imugi.

Lee Yeon transforms into his nine-tailed fox form, angered by an evil shaman who harms the innocent to perpetuate her own immortality.

A clip from Tale of the Nine Tailed (2020), episode 3, streamed on Netflix.

Constructing animistic masculinity in Anthropocene Northeast Asia

Although they also possess stereotypically masculine traits (e.g. protectiveness, typical male fashion, and toned muscular physiques), the two characters demonstrate animistic and stereotypically feminine traits that challenge both patriarchal and ‘soft’ masculine traditions.

Kim Shin and Lee Yeon demonstrate sophistication in emotional intelligence, stereotypically associated with femininity. They are sensitive to the minor shifts in feelings and moods, and attend to these shifts reverently. They are patient in self-care and care for others. They are also respectful towards following the appropriate ways of decision-making. With their supernatural powers, they could have simply destroyed everything that stood in their ways, but they did not. Kim Shin and Lee Yeon understand their existence as fundamentally sanctioned by greater powers in the supernatural and spiritual realms. During difficult decision-making moments, they consult holy references and seek God’s permission. They are also critically conscious of Karma, fate, and the spirituality of animals and surrounding ecological features. These traits characterise a masculinity that does not follow the patriarchal binary gender constructions. For example, Kim Shin clarifies very early on his karmic understanding of love that disregards physical lust: “I have lived for more than 900 years. I am not looking for someone pretty. I am looking for someone who can see something on me” (Episode 2, 22:28).

The Samshin (the goddess of birth and fate), who watches over Kim Shin, manifesting as an ordinary grandmother selling vegetables by the street. The Gods appear in various forms.A still from Guardian: The Lonely and Great God (2016), episode 1, streamed on Netflix.

The Samshin (the goddess of birth and fate), who watches over Kim Shin, manifesting as an ordinary grandmother selling vegetables by the street. The Gods appear in various forms.A still from Guardian: The Lonely and Great God (2016), episode 1, streamed on Netflix.

The two characters also demonstrate animistic consciousness. Kim Shin has repeatedly mentioned that he is part of the wind, the rain, and the snowfall. His emotions are connected with flowers, rainfalls, and the moon. Lee Yeon, a mountain guardian, respects and communicates with the trees, animals, waters, wind, and ancient spirits, across the mountains. Additionally, common to both artefacts, the animals and beasts (e.g. butterflies, fireflies, bear, tiger, fox, goblin, and owl) have been portrayed as mythical spirits able to communicate warning and guidance. In Guardian, for instance, the recurring butterflies turn out to be another physical manifestation of God, in addition to male and female figures. In Lee Yeon’s case, a group of fireflies guide him with their bioluminescence towards Nam Ji Ah who has been trapped by an evil shaman on an island at night.

Fireflies in a forest respond to Lee Yeon’s call for help to look for Nam Ji Ah.

Fireflies in a forest respond to Lee Yeon’s call for help to look for Nam Ji Ah.

A still from Tale of the Nine Tailed (2020), episode 3, streamed on Netflix.

Geology, meteorology, zoology, animism, femininity, religion: these otherwise separate epistemologies come together to construct an animistic masculinity in Kim Shin and Lee Yeon and substantiate new geopolitical conceptions in Anthropocene Northeast Asia. This animistic masculinity rebuilds a respectful and mutualistic relationship between the human and the non-human, be they plants, animals, rainfall, or the moon. Here, an animistic respectfulness responds to the multidisciplinary literature in which social scientists, geologists, and anthropologists seek animistic responses to the Anthropocene, where ‘Enlightenment Man’ has effectively severed ties with the forces of Nature and continues trying to overpower Nature. Kim Shin and Lee Yeon teach that Nature, Gods, and spirits can never be challenged and must be respected reverently, and that the real geopolitical concern in the Anthropocene should be a move away from the centuries-old condition where sovereign nation-states fight for resources, development, and imperial domination. Folkloric as they are, Kim Shin and Lee Yeon’s anger at the evil spirits allegorise Anna Tsing’s “outrage at the destructive works of Man” (2016: 5).

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Sing Fei Teoh is a doctoral candidate in communications geography and environmental media at the School of Humanities, University of Nottingham Malaysia. With keen interest in eco-critical and post-human traditions in Anthropocene Northeast and Southeast Asia, Sing Fei’s research dissects and compares the spatial and geopolitical implications of contemporary folkloric, Indigenous, and feminist sources in Malaysia, Indonesia, South Korea, China, and Japan.