Feeling blue: A Critical Commentary on Singapore’s Household Recycling Practices

https://doi.org/10.25542/nv9r-y149

“…waste is a mirror of humanity, a means or intermediary by which to reflect on ourselves.” - Joshua Reno

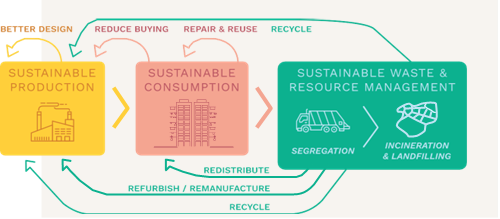

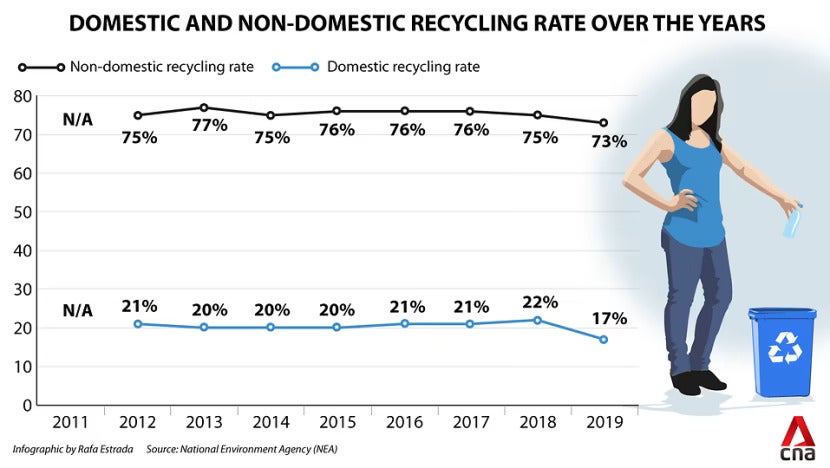

In 2019, Singapore’s Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MSE) drafted its inaugural Zero Waste Masterplan, which maps out some pathways for building a “sustainable, resource-efficient and climate-resilient nation”. One of these pathways is a move towards a circular economy. As opposed to a linear “take-make-dispose” model, a circular one endeavours to transform waste (outputs) into resources (inputs), or in Sembcorp (a Public Waste Collector in Singapore)’s parlance, to convert “trash into treasure”. Household recycling has featured prominently in Singapore’s environmental policies even before its plans for a circular transition. However, since the official implementation of the National Recycling Programme (NRP) in 2001, household recycling has gained little traction. Singapore’s household recycling rate had been consistently low (hovering between 19 to 22 per cent from 2012 to 2018). In 2022, it dropped to 12 per cent, the lowest in a decade. This is far from its target of a 30 per cent household recycling rate by 2030.

Against this backdrop, fixing the analytical gaze on the city-state’s blue recycling bins is instructive in illuminating quotidian practices related to the handling of post-consumer waste. As opposed to the itinerant karung guni (a colloquial term for a rag-and-bone man) and the bi-weekly door-step collection of reusable items, the blue bins are an everyday presence in residential neighbourhoods. We draw on qualitative empirical material from ethnographic observations and interviews to argue that there is a disjuncture between top-down recycling policies and actual “recycling” practices on the ground. Most of these findings come from 114 interviews with members of Singaporean and non-Singaporean households.

Here, we seek to spotlight the limitations of Singapore’s household recycling infrastructure (commingled bins) and the implementation of national recycling polices (the National Environmental Agency's "recycle right" campaign as well as the placement of recycling bins). In particular, we posit that the contamination of the blue bins by organic and other non-recyclable waste is responsible for Singapore’s "recycling blues". We suggest that the contamination of recyclables stems from several factors:

- a nonchalance towards pro-environmental behaviours,

- the lack of a moralistic or disciplinary framework that rewards or punishes good or bad segregation practices, and,

- a heavy reliance on lowly-paid migrant workers to perform essential waste work, such as cleaning up common areas and emptying blue recycling and general waste green bins.

We posit that a society focused on neoliberal productivity (i.e. waged employment and other active engagements in sectors defined as valuable) and accustomed to outsourcing waste work (i.e. largely construed as menial, "unproductive" labour) is antithetical to cultivating a culture of sustained engagement with waste.

Zero Waste Aspirations and the Household Recycling Landscape

Singapore’s recycling polices are currently subsumed under its Zero Waste Master Plan, which reflects its ambition of producing minimal waste by 2030. Domestic or household recycling can theoretically reduce waste and close circularity loops by transforming post-consumer “waste” into raw materials for another round of “sustainable production”. As a small island-state, space for waste has always been a governmental concern—Semakau landfill is expected to be full by 2035, a decade earlier than projected. The state’s impetus for instilling a recycling culture is thus pre-emptive and fear-driven, rather than guided by moralistic and environmental concerns.

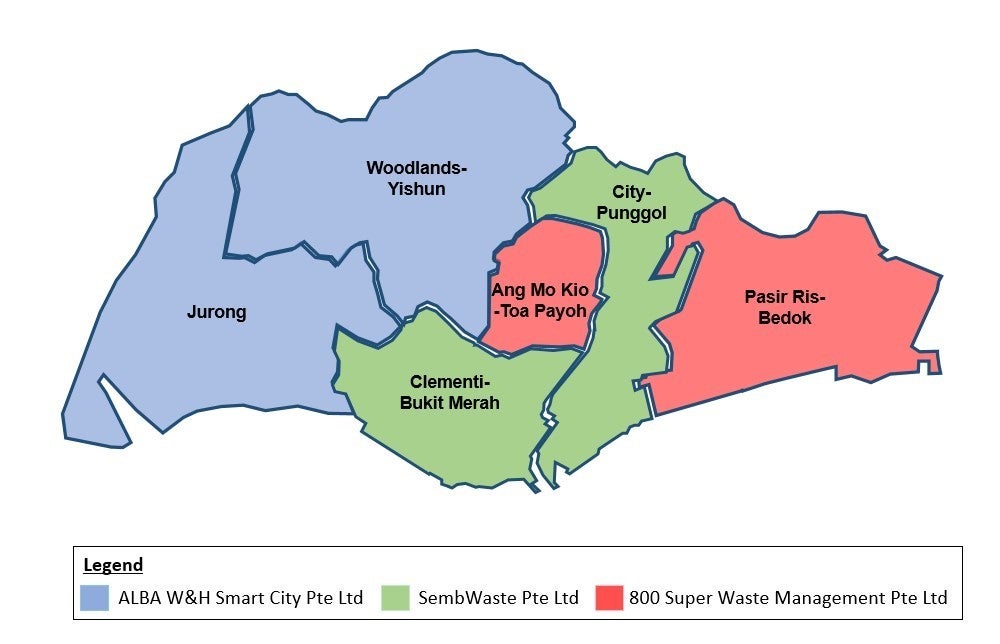

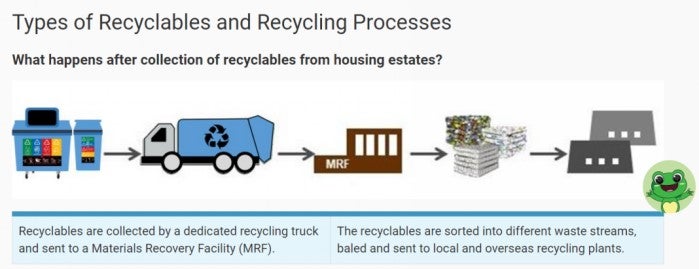

Under the NRP, the three public waste collectors (PWCs) licensed by the NEA have to provide residential districts with blue recycling bins and collection services. These blue recycling bins are commingled, which means that paper, glass, plastic, and metal recyclables are deposited in the same bin. These bins are usually bigger in public housing estates (660L in size) than in landed housing areas and are collected thrice per week by blue recycling trucks. The recyclables are then sent to a Materials Recovery Facility (MRF) to be sorted by material, baled, and then redirected to other recycling facilities for further processing.

Commingling and Contamination

The contamination of recyclables has been a persistent problem in Singapore; the contamination rate in blue bins has hovered around 40 per cent in the last six years. Although it has been reported that commingled recycling systems can contribute to higher rates of contamination, such a system has still been retained in Singapore. The Minister for Sustainability and the Environment, Grace Fu explains that a commingled system generates a lower carbon footprint while rendering “recycling easier […] as it relieves residents of the effort and time needed to segregate different types of recyclables”. Sociologists Wheeler and Glucksmann (2015) call this effort, which involves the unpaid labour of sorting, cleaning, and bringing recyclables to the recycling point, “consumption work”. Similar to what the minister points out, they have evinced that “clean sorts” (segregating recyclables based on materials) demands more effort/time than “dirty sorts” (dropping recyclables in a commingled receptacle). But the prevalence and correct execution of this recycling consumption work are integral to the operationalisation of a circular waste management system, failing which it becomes unviable.

In our ethnographic interviews, a couple of our interlocutors, who are better informed about the intricacies of household recycling, have identified the drawbacks of depositing different grades/types of plastic “recyclables” into the same bin. Besides Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and High Density Polyethylene (HDPE), other “lower” grades of plastic material such as plastic bags and styrofoam packaging are not actually recycled (even if they are technically recyclable) and act as contaminants. These “recyclable contaminants” will have to be removed at the MRF and sent to the incinerator.

Although the commingled blue bins are “dirty sorts”, bottles/containers still have to be rinsed to reduce contamination from food waste. Food waste causes paper to disintegrate, while decomposition reactions can adversely affect plastic recyclables. In other words, contamination in the blue bin stems from poor recycling attitudes (e.g. nonchalance, apathy) and practices (e.g. not rinsing containers/bottles, wish-cycling, depositing non-recyclables into the blue bin) rather than commingling. Conversely, apathy could be engendered by the "deplorable" state of the blue bins. Most of our interlocutors are reluctant to recycle because the blue recycling bins below their apartment blocks are so badly contaminated with non-recyclables and organic waste that they are indistinguishable from green general waste bins.

Our ethnographic observations confirm that these blue bins are routinely “polluted” with rotting food and dripping liquids. One of our interlocutors has provided an “emotional testimony of [her] experiences”, by sending us a picture of her commingled recycling bin at her void deck. The picture presented “incontrovertible proof” of how “gross” the bin was, which had “a swarm of flies”, thereby justifying her decision “to not go anywhere near it” (and therefore not recycle her waste). The images of the blue bins we have captured exceed their visual mimetic qualities—they are a form of affective "witnessing", entailing an “acknowledg[ement] of potentially difficult realities”.

Apart from the visceral disgust that our interlocutors have had to contend with in confronting “matter out of place” (e.g. used sanitary napkins and diapers in the blue bin), they are also cognisant that whole batches of “recyclables” can go to waste even with just a small amount of contaminant. Some have also seen blue bins being emptied into general waste trucks, thereby contaminating the recyclables. Others have reflected that Singapore is not only “late” in joining the pro-environment movement but is also perfunctory in encouraging a moral culture of recycling. The lack of an overarching moral economy gives rise to heterogeneous segregation practices, whereby individuals interpret rules based on their convenience. Meanwhile, some pro-environment residents prefer to sell or give away their newspapers, cardboard boxes, other recyclables, and reusables to a karang guni who visits irregularly, despite having to store these items at home for longer periods of time. Not only does this ensure that the recyclables are uncontaminated and would be recycled, interactions with a karang guni also fosters inter-personal relationships compared to the impersonal act of depositing recyclables into a recycling bin.

Other Limitations in Design and Placement

Besides contamination, the design and placement of the blue bins are less than thoughtful. In public housing neighbourhoods, these bins are usually placed outdoors and along roads for easy collection by trucks. However, such logistical considerations discount the exposure of the recyclables to heavy rainfall all year round, which contaminate and degrade paper materials. Older “versions” of the blue bin have covers with a small open slot, and rainwater often seeps in. As the small slit makes it hard to fit bulkier packaging waste, the cover of the bins are occasionally ripped off and never replaced. Despite newer, improved iterations of the bins, which are fully covered and larger in capacity, residents still tend to “dump” their recyclables beside the bin rather than inside it.

Remedial action and the Perils of Singapore’s Socio-institutional Climate

NEA continues to pump resources into boosting the country’s household recycling rates despite the limited progress after two decades of institutional effort. To bring down the high contamination rates, NEA has recently rolled out a #RecycleRight campaign exhorting members of the public to “treat the (anthropomorphised) Bloobin right”, while introducing Bloobin sticker packs for app-based messaging services. Posters of recyclable items have been plastered on all blue bins. Additionally, households have been given a foldable and reusable mini-Bloobox for keeping their recyclables at home. Unfortunately, many of our interlocutors have shared that the box is too small to fit their recyclables and are often used as storage boxes, evincing how well-intentioned, top-down plans have unforeseen outcomes in the absence of a socio-moral framework. NEA has also partnered with F&N Foods to introduce Reverse Vending Machines (RVM) for the collection of empty plastic bottles and aluminium cans. However, these RVMs are not as ubiquitous as the blue bins and are often at capacity, which means the blue bins remain the primary receptacle for household recyclables.

The affective evocation is fear-driven and sympathy for an impersonal bin, instead of a moral one such as environmental stewardship. Without punitive measures, a fear-driven rhetoric has failed to condition public behaviour. Given that Singapore is "renowned" for its aggressive fining of arguably minor infractions, a handful of our interlocutors have expressed surprise at the absence of a "recycling police" and that contaminating a whole batch of recyclables (and wasting the time/effort of others who have diligently recycled right) is not a punishable offence.

Furthermore, waste is predominantly invisibilised in Singapore. The landfill is on the separate island of Semakau, hence far-removed from everyday life; invoking a spatial crisis for waste is therefore hard for residents to comprehend. Initiatives targeted at raising the “quality” of consumption work do not address the main cause of contamination: poor segregation at source. However, good recycling practices (e.g. depositing only recyclables and rinsing them) are unlikely to happen without strategies to change attitudes or enforce a change in actions. As a society driven by economic pragmatism, the handling of waste is typically construed as a waste of labour/time. This is compounded by provisions made by the paternalistic state to clean up after its residents. One of our interlocutors has even absolved themselves of any responsibility to deal with household waste since “the government charges conservancy fees for waste disposal”.

The blue bin in Singapore is a lonely, forlorn, and unloved figure. It is neither culturally integrated as other mascots nor backed by discourses on environmentalism, sustainability, and ethics. To draw from Gay Hawkins, although recycling does not sensitise us to “how much of the waste we make comes from exploited labour and goes to an exploited nature”, it serves as a first step towards an “ethics of waste”. An ethics of waste is embedded in a system of values that extends beyond the household and this country. It requires the cultivation of a new form of moral subjectivity, which is attuned to the historical culture of Singapore’s society, alongside respect for waste workers. Consequently, a radical reconceptualisation of value and waste beyond narrow economic terms is imperative if the goal is to change the population’s relationship with waste and their waste disposal practices.

Kamalika would like to thank Dr Remi De Bercegol and Nicolas Christie for their advice and support. Kamalika's research is supported by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister's Office, Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme [NRF2020-ITC003-0001]. Qian Hui’s research is supported by the Ministry of Education Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 2, [MOE-T2EP40121-0005; PI: Brenda Yeoh].

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

Kamalika Banerjee is a Research Fellow at CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) at CREATE, Singapore. Her postdoctoral research focuses on multispecies interactions in the waste infrastructure in Singapore and the politics of recycling. Her broad research interests include postcolonial urban theory, state and civil society, and politics and poetics of waste.

Tan Qian Hui is a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Migration cluster at the Asia Research Institute. Her research interests are in intimate relationalities, embodiment and more recently, sustainability politics are often informed by critical feminist as well as queer theoretical perspectives. As a socio-cultural geographer by training, her work has been published in Gender, Place & Culture, and Social & Cultural Geography. At ARI she works on an interdisciplinary project on plastic waste management in households across Singapore and Australia.