“It began with a love and respect for animals”: On writing ‘Mao’s Bestiary’

I still remember the first time I asked a question in an open forum as a PhD candidate. It was at a public lecture given by a prominent British professor who visited NUS in 2011. He expounded on the idea of equal rights across all species. At the end of his lecture, I stood up and asked: ‘If all species, meaning humans and animals, are equal, how is it that we still eat them? Why is it that I’ve tried so hard to be a vegetarian but failed?’ The audience burst into laughter. The professor never answered my question.

Ten years later I’m a committed vegetarian, though I still ponder the question I posed to the visiting professor. Since young I loved but also ate animals, growing up in a family with little or no sympathy for other species. ‘They are nothing but beasts’ my father or grandmother would often reply to my expressions of empathy. My ancestors came from Guangdong province in China’s far south. Chinese mainlanders make much of the differences between Southerners and Northerners, and the former are stereotyped as having a voracious appetite for any kind of animal: ‘all those that fly in the sky, all those that crawl on earth, and all those that swim in the waters’ as a common saying goes. This is sometimes linked to a legacy of poverty and periodic famines.

While the cultural dimension is there, someone has had to organise the transformation of wild species into food, or medicine, and in the contemporary period this has become an industry, and an unsustainable one at that. Though poverty might have contributed to traditional consumption habits, it is likely that class status now plays a more important role in the appetite for exotic wildlife. A sub-set of the wealthy, all over China and its diaspora, prize the consumption of animals as food or medicine in relation to their rarity, and even their high price.

No doubt, exotic animals have historically been exploited both in the West and East as symbols of power and prestige. But the lack of animal rights in China, coupled with a growing appetite among rich and powerful Chinese for wild meat has certainly put the country on the watchlist. This demand not only drives huge profits for the illegal wildlife trade, but is fast leading to the extinction or endangerment of species as far afield as South America, if not contributing to zoonotic disease.

My first exposure to the medicinal wildlife trade was a trip I made in 2009 with an NGO to a ‘bear farm’ in Boten City, Laos. I told that story in the Introduction to my book, so I would not repeat it here. But my organisation was in Laos to investigate an epidemic among the bears, who ironically were succumbing to disease even as their bile was being sold as medicine in expensive gift boxes at nearby casinos. The sense of injustice that I felt for the tightly-confined and diseased animals at the time helped decide my PhD topic.

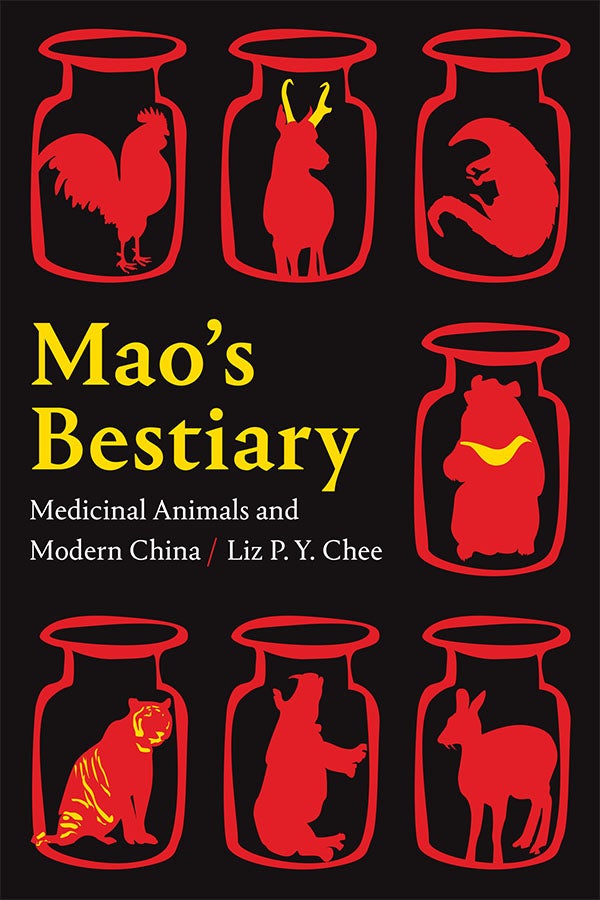

I wanted initially to just discover the origins of bear farming, which I knew to be recent despite an age-old use of bear gall bladder in Chinese medicine. I soon discovered that this was just one aspect of a much larger and longer historical process I termed in the book as ‘faunal medicalisation’: the industrial-scale conversion of increasing numbers of species and parts of species into medicine, which began in China around the time of the Great Leap Forward and continues on a global scale today.

My book, Mao’s Bestiary: Medicinal Animals and Modern China (Duke University Press, 2021), traces an aspect of Chinese medicine and pharmacology that had been almost completely neglected by historians despite, or perhaps because of, its controversial nature. Although the book was finished just at the onset of Covid-19, and does not deal directly with zoonotic disease, it helps fill the gap in our knowledge of how and why ‘medicinal animals’ proliferated in state medicine of China, despite being largely ignored in the years just after the Revolution.

While animals (alongside plants and minerals) have been accorded medicinal value from ancient times in China, it was not inevitable that this would carry over into the hybrid, and self-consciously modernising set of practices that became known in the rest of the world as ‘Traditional Chinese Medicine’ or TCM.

Animals were especially prized because of the much-needed foreign revenue they would generate through export to the Southeast and East Asia, where there was demand from the Chinese diaspora.

The process of faunal medicalisation relied not only on canonical Chinese references or practices, but borrowings from Soviet medicine, the production quotas of the Great Leap Forward, and even the politics of the Cultural Revolution, when ‘chicken blood therapy’ became a sudden health craze. This particular zootherapy – which involved injecting raw chicken blood into human bodies - is remembered today as a unique eccentricity, motivated by political zealotry.

Mao’s Bestiary contextualises it as one of many examples of hybrid faunal therapies of the period using toads, geese, insects, and other types of animals wild and domestic. Their inventors’ claims that animal tissue could act as powerfully as antibiotics and other Western drugs, even curing cancer and other diseases then testing the limits of biomedicine, would help set the stage for the many exalted curative claims of the present day which drive the illegal and legal wildlife trades.

While the medicinal use of animals was traditionally limited by both classical recipes and practical availability, faunal medicalisation as a modern process knows no such bounds. In fact, the term ‘traditional’ is abused. My research demonstrates that much of the hyper-medicalisation of species we see today has origins as recent as the 1950s, and runs through scientific labs, commercial farms, and even foreign-based research projects. This complicates the idea that faunal medicalisation (using animal parts and tissues for drug-making) is fully embedded in canonical texts or ‘the thousand-year experience of the Chinese people’.

The institutionalised ‘farming’ of formerly wild-caught animals for their parts and tissues, partly to fuel increased overseas export, was an important legacy of the early Communist period, and increased the types and availability of species considered medicinal. Even for ‘traditional’ medicinal species, the logic of production sometimes meant increasing the claimed scope for efficacy, and infusing even more of an animal’s body parts with curative powers.

The Tokay Gecko, for example, was first farmed for its re-growable tail, but is today sold as a whole body on a stick. Scientific studies also expanded treatment regimes and delivery methods, and labs worked on substituting the tissue of more common animals for those facing extinction through medicalisation (e.g. water buffalo horn used to replace rhino horn). Faunal medicine made the transition to capitalism under Deng’s reforms, when bear bile farming – a technology pioneered in North Korea and based on Japanese scientific research - became the signature and most controversial of all Chinese faunal drug industries.

I am, by the way, a user of Chinese medicine myself, and my research in China would not have been possible without the support of Chinese medical doctors at the Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine and other institutions where I researched my PhD dissertation. There is a growing concern that exploitation of animals has become an Achilles Heel to the modern practice of Chinese medicine, and I hope that my book will help demonstrate that “the burden of history” need not weigh down efforts at reform, which are now widespread among practitioners and users.

I am currently applying for a grant to further my research on the medicalisation of wildlife, and expand it beyond China to the rest of East and Southeast Asia. There is so much more to understand, particularly about the relation of Chinese state medicine (and the medicinal animal trade) to the other Chinese medicines of this region, and even other indigenous Asian medicines, some of which also use and trade in faunal drugs.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.