Visualising “Asia as Future” through Speculative Southeast Asian Aesthetic Urban Futures

https://doi.org/10.25542/613k-vgw2

"The view from Asia is that history has not ended but returned." - Parag Khanna

If political scientist Francis Fukuyama's sweeping notion of “the end of history” has bookended the global cultural and political discourse of the 20th century in its last decade, then the global discursive landscape of the 21st century can be described as replete with “futures”. Governments, consultancies and businesses generate administrative and financial futures by applying technoscientific apparatuses, calculative forecasting and planning techniques, and future-making policy approaches. These “futures” are projective and speculative in the conjectural and financial sense, planetary in scale, and are usually concerned with technological innovation and its ubiquitous impact on the future global economy, as well as “sustainability” and “resilience” against the backdrop of global ecological devastation.

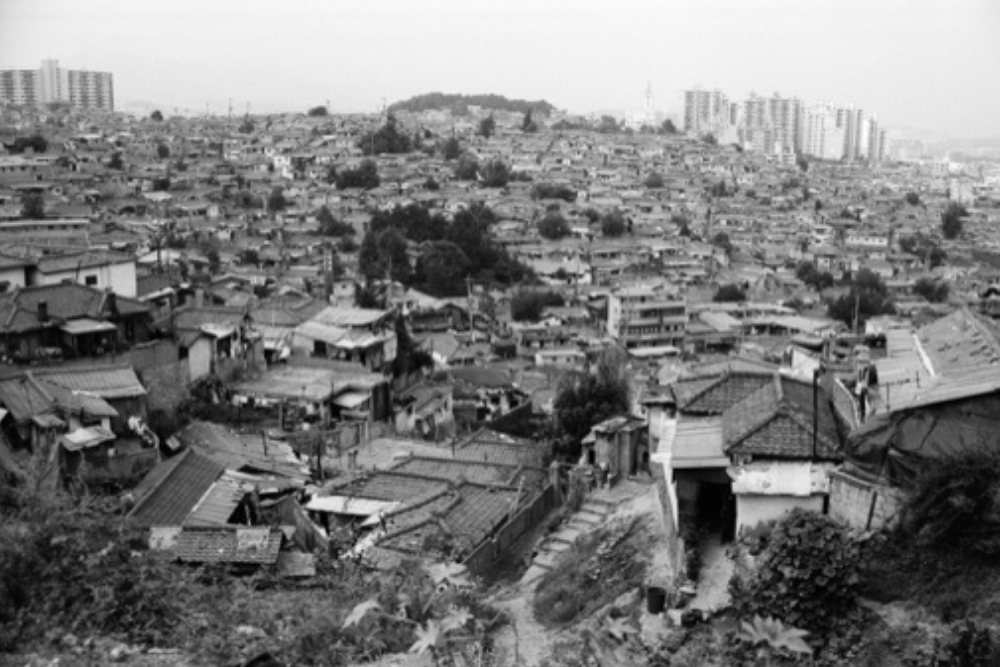

Projected as a region exemplary for its rapid economic development, Southeast Asia is a fertile ground for the production and promotion of urban futures. Identified by the United Nations as the region with 54% of the world’s urban population, Asia is currently experiencing rapid urbanisation on a massive scale and is projected to become the fastest urbanising region in the world. In his book The Future is Asian, “thought-leader” Parag Khanna describes Southeast Asia as one of the relatively more economically and politically integrated regions in Asia. This is affirmed by reports from consultancies and thinktanks that regard the region as a key global manufacturing hub with potential for further developmental expansion. Projections of economic development and growing middle-class populations in Southeast Asia run parallel to administrative and financial projections of rapid urban development. Urban futures are reflected in the activities and landscape of dense global financial centres such as Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok, as well as in the capitalist urban and economic expansion of regional city centres such as Hanoi and Phnom Penh. However, the landscape of Southeast Asia's post-colonial development is characteristically uneven, with non-urban areas especially affected by intensive environmental exploitation driven by the extraction, production and export of natural resources.

A common sight in fast urbanising Southeast Asia. Shutterstock.

These administrative and financial urban futures are “conjured” through aesthetic processes that render such futures visible and coherently intelligible—and hence possible—in attractive and sensory forms such as masterplans, architecture, and urban showcases. Southeast Asian administrative and technological urban futures project success through modes of design and narrativisation, enacting an aesthetic politics that organises urban citizen consensus around middle-class ideals of particular infrastructural futures considered to be desirable. These urban futures contribute to the inflationary rhetorical notion of “Asia as Future” which promotes “Asia” as potentially the world’s most influential and developed region, but overlooks the diverse and unequal social, political and material conditions and the range of concerns of the “Asian” urban present. However, artists, writers, and creative practitioners based in the region have produced aesthetic urban futures in the form of speculative fiction and art which can offer critical perspectives or counterpoints to these administrative and financial grand narratives that generalise and trump the economic and technological development of the region, as well as exclude the aspirations of marginalised and displaced communities in the urban developmental process.

I first discuss how aesthetic urban futures are recursively produced with the use of design and narrative. One example is the High-Tech/Eco-tech Superpark, Gardens by the Bay, which has become representative of a futuristic eco-technological urbanism sited in the “Asian Tiger” technocratic city-state, Singapore; another is Jakarta’s megastructural Great Garuda Seawall Masterplan project. Despite the disparate urban profile of the two cities, these projects demonstrate urban ambitions and how creations of design and narrative dynamically shape and become shaped by the features of material landscapes to that project’s urban ambition. I then discuss the works of speculative fiction and art by Singapore-based artist-writer Jason Wee and Jakarta-based artist Tita Salina presented during the Roundtable on Speculative Southeast Asian Aesthetic Urban Futures (ARI, May 31, 2022) that sought to unsettle the discursive topoi of the Southeast Asian urban future.

The speculative image of the eco-technological planetary urban future

Designed by UK-based WilkinsonEyre Architects and landscape architects Grant Associates, the Superpark Gardens by the Bay is a highly profiled example of how a new state-sponsored public park has become a performative emblem of Singapore's futuristic urbanism and a global icon for urban sustainability. While the Superpark features renewable energy technologies such as photovoltaic cells and a biomass generator, it is more globally known for its distinctive ecological aesthetics inspired by other actual and imaginative fantastical landscapes such as the Valley of the Giants in Western Australia and the forest of Studio Ghibli's Princess Mononoke. Due to its otherworldly design, the Superpark has become a widely-circulated visual citation for a speculative geography of the urban future. It functions as the attractive imaginary of Singapore as a "City in a Garden", an official policy narrative upheld by international governmental organisations as a model for its clean and biodiverse post-industrial environment.

Supertrees at Gardens by the Bay, Singapore. Shutterstock.

Supertrees at Gardens by the Bay, Singapore. Shutterstock.

The Superpark has simultaneously evoked utopian and dystopian reactions and projections through its Eco-tech aesthetics that reflect contesting opinions on the prospects of technological environmental control. It has become a flagship image of 'Solarpunk': a science-fiction/speculative subgenre that projects the optimistic possibility of a more habitable world in the face of environmental crisis through the inventive use of technology with respect to nature. To some, the Superpark is a reference that inspires imaginative fiction and an operative model for design theories such as biomimicry (i.e., material and structural design which follow patterns and mechanisms of nature) that support the notion that nature and human beings can flourish in cities traditionally associated with environmental pollution and degradation.

But others, such as Singaporean academic Jerrine Tan, view the aesthetics of the Superpark as an updated extension of the dystopian sci-fi genre “Cyberpunk”, where high-tech metropolises dominate ultra-capitalist business conglomerations and authoritarian governments that use technology for citizen surveillance and control. Inspired by the post-apocalyptic industrial urban landscape and zaibatsu business empires of “Tiger” economy Japan in the 1980s, cyberpunk depicts problems of extreme urban sociopolitical dysfunction. This theme is similarly explored in the third season of the American dystopian sci-fi television series Westworld, in which “Vertical Green” Singapore landmarks that integrate vegetation into infrastructural surfaces are employed as the backdrop of Los Angeles in 2058. Onscreen, these landmarks also lend the impression that global warming will be managed through the use of technology in the future city. However, the plot’s extended elaborate power struggle played out between sentient clones, human beings and technological conglomerates critiques this urban picture by implying that the green veneer of these landscapes merely adds superficial allure to the socially exploitative nature of the future city.

Screenshot from Westworld featuring Marina One as one of the locations shot in Singapore that displays tropical greenery incorporated within the building structure. Credits: Yahoo Singapore.

Screenshot from Westworld featuring Marina One as one of the locations shot in Singapore that displays tropical greenery incorporated within the building structure. Credits: Yahoo Singapore.

These sci-fi/fantasy projections demonstrate the recursive dynamic of futural urban imaginaries: fictional landscapes, narratives and concepts are generated from architectural structures and physical sites through methods of design and narrativisation. These designs and fictional narratives subsequently reconfigure structural forms and animate the planetary imaginaries of high-profile megastructures such as Gardens by the Bay and Jakarta's Great Garuda Seawall masterplan proposed in 2014 to prevent Indonesia’s most populous city from further sinking, especially in the face of rising tides. Jakarta has been ranked as “the world’s most environmentally vulnerable city”, facing problems of flooding, poor infrastructure, and urban sprawl. Informal settlements have become a part of the city resulting from unregulated rapid urbanisation and population growth. The masterplan involves the creation of 17 reclaimed islands in the northern coast of Jakarta in the shape of the Garuda, the mythical bird-like demigod and the national symbol of Indonesia. After project designer and Dutch architect Gijs van den Boomen observed that Jakarta Bay looked like a bird, Indonesia’s political elites showed more interest in the shape of Jakarta Bay imagined as the Garuda. While the masterplan was originally conceived as a defensive plan to reinforce Jakarta’s current coastal seawall and to build eastern and western offshore sea walls that would bound Jakarta Bay, it is increasingly being financed through private real estate development, thus shaping its status as a plan for luxury apartments.

Design of “The Great Garuda” seawall at Jakarta Bay. Kuiper Compagnons.

These aesthetic ecological urban projects add to the rhetorical "big picture" of “Asia as Future” and of Southeast Asia that elides a more socially and ecologically complex reality for those who live and work in the region's individual cities. In the case of the Superpark, its glamour overshadows the presence and contribution of unskilled or semi-skilled migrant workers brought in from other parts of Asia, such as Bangladesh, to perform precarious construction and maintenance tasks for minimal wages. Recently subjected to severe lockdown conditions during the pandemic, these workers were perceived as pathological vectors by the state. In northern Jakarta, plans for luxury high-rise apartment construction at the Great Jakarta Seawall have exacerbated poor environmental conditions and led to the eviction of local communities living in the area. While little has been officially reported on the masterplan’s progress, the remaining communities are reportedly living with their garbage bounded by the seawall. The experiences of these marginalised populations embody an apocalyptic dimension of urban living usually left out of administrative or financial urban future visions.

In Short, Future Now and Ziarah Utara: The fragmentary future, present and past in speculative fiction and artistic practice

Speculative fiction is a literary genre featuring sci-fi and/or fantastical elements that involves the thematic exploration of socio-political concerns, particularly told from minority perspectives that challenge ideological hegemonic viewpoints and orders. Southeast Asia-based speculative fiction and aesthetic speculative landscapes have significantly emerged in recent years in the form of speculative novels such as Pablo Bacigalupi’s climate fiction The Windup Girl set in 23rd-century Bangkok/Thailand, visual art, and new literary journals/anthologies such as LONTAR. The urban landscape is made alien and juxtaposed with science-fictional and mythic elements in particular speculative narratives and performances. In presenting alternate futural realities by evoking other temporalities, they provide critical and ethnographic counterpoints from various scales that illuminate the overlooked implications of contemporary visions of market and technology-oriented state-driven urban futures endemic to this region.

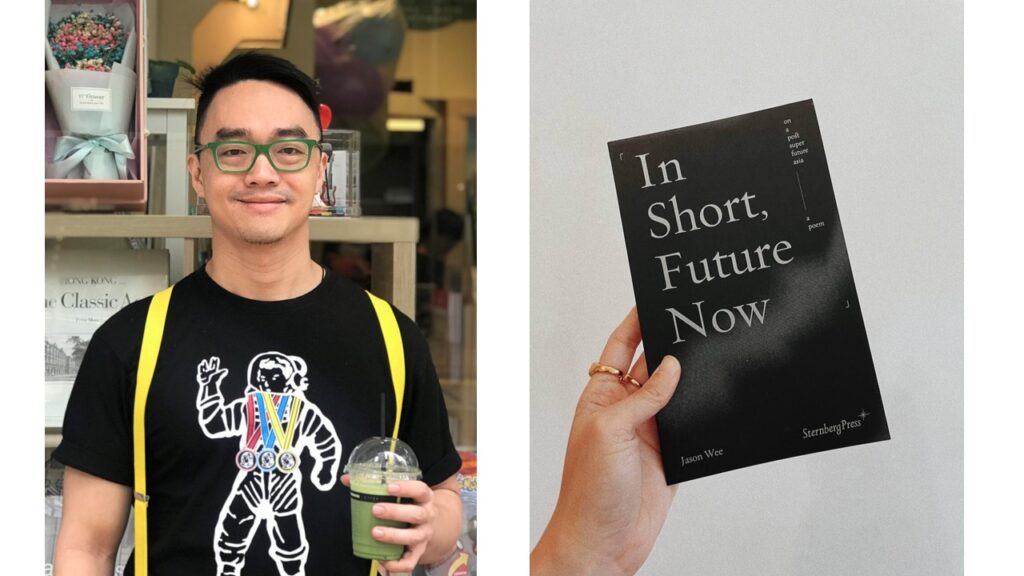

In the ARI Roundtable, Singapore-based artist-writer Jason Wee introduced his speculative poetry publication In Short, Future Now. The eventual product of a series of experimental creative writing workshops based on the theme of a “post super future Asia”, the work could be read as a critical response to the boosterish trope of “Asia as Future” in its objective to create and present a more politically radical formulation of the trope where “Asia” is an imagined landscape freed from geopolitical coordinates. Describing his work as concrete poetry meets science fictional haiku, In Short Future Now is written through a feminist/queer postcolonial perspective. Wee attempts to imagine “Asia” with respect to future developments such as rising sea levels from climate change, developments in technology, and their possible sociopolitical effects and impact on popular culture. The future is rendered in post-apocalyptic scenes of emotional alienation that present an alternative future based on the current urban developmental trajectory of Asia, with imagery of archipelagic cities as islands unmoored like colonial ships, empty museums, and 600-storey apartment buildings. Wee mobilises the archipelagic and the siphonophore to conceptualise “Asia” as an assemblage of territories. He presents a “plastic poetics” that juxtaposes phrases in various Asian poetic forms as well as epigraphs, citations, and other fragments. In this way, Wee’s verse relates a pluralistic notion of “Asia” that is disorientating but also potentially liberating. Any geographical, historical, and socially coherent notions of “Asia” are lost in an oceanic landscape, with fragments of the past breaking apart and also drifting together in random configurations.

Jason Wee (left) with his poetry publication (right). Photos courtesy of the author.

In contrast to the vast speculative landscape of “Asia” evoked through Wee's poetry, Jakarta-based artist Tita Salina's ongoing project Ziarah Utara (Pilgrimage to the North) with her partner Irwan Ahmett, in collaboration with geographers Hannah Elkin and Jorgen Doyle, is focused more specifically on the shrinking coast of Northern Jakarta. Since 2018, Salina and her collaborators have mapped the area over walks, noting the complex social and environmental dynamics of the Northern coast and Jakarta Bay emerging from the interaction and impact of different communities (which include a gated residential community, the mafia and kampung communities facing eviction) and the heavy flooding and pollution at the coast. One affected community is that of the becak (three-wheeled rickshaw) drivers who were agricultural labourers compelled to move to Jakarta for work due to commercial and illegal land grabs. Since the 1950s, the becak has been stigmatised by politicians as unsightly and backward, and even confiscated and thrown into Jakarta Bay in the late 1970s to the 2000s. As Salina comments, the becak has no place in Jakarta's municipal future plans for sustainable mobility and net zero emissions by 2050, even though they utilise no fossil fuels. With the help of Pak Kwik (“Mr Quick”), a friend of former President Suharto, who sets fish traps in the sea at the site of the disposed becaks, Salina and Ahmett were able to identify the location of these sunken vehicles which has now become a reef in the sea. Salina presented a segment from the video work "35 years at -33 metres" which features divers retrieving the becaks from the depths of the sea juxtaposed against a defiant protest song of the becak drivers. Through the resurfacing of the submerged becaks, the political memory and voices of the marginalised becak drivers oppressed during the Suharto dictatorship regime are brought back into present public consciousness and commemorated as part of the history of Jakarta Bay.

Tita Salina (left) with the fragments of the becak retrieved from the sea (right, credits to Irwan Ahmett). Photos courtesy of the author.

Southeast Asia as an urban futures frontier

In the Roundtable, discussant Associate Professor Daniel Goh described Southeast Asia as an “urban futures frontier”. Southeast Asian urban and economic futures and realities greatly differ across the region, but they are similarly shaped by the hegemony of speed as dictated by financial and administrative targets and plans for infrastructural and real estate expansion, with time as a defining vector. Government agencies and businesses engaged in inter-Asian urban referencing within the region's aspiring global cities produce hyperreal aesthetic futures through the deliberate and rapid transformation of public space according to “world-class” standards and the production of cultural narratives that align the identity of urban spaces with commercial and administrative agendas, which also involve the use of “state of the art” technology to mitigate or solve social and ecological problems. These futures render public memory as “disappearing” in its virtuality. As Goh offered, Asian cities now turn Western notions of urban futurism on their heads and even incorporate critiques of Asian-inspired futurisms, such as the case of Cyberpunk.

The works discussed in the Roundtable are two speculative responses to the experience of urban change based in the region. While these artistic works contrast in form and context, they both are thematically centred on the material fragment, which exemplify the consequences of ecological destruction and the rapid transformation of public memory. In Wee's postcolonial epic of the Asian future, any claims to origin and coherence are confounded by the self-contained and combinatory fragment. Salina and Ahmett's work resurfaces the discarded and wrecked becak as a persistent reminder of the bodily presence and political resistance of the becak drivers whose collective urban future (amongst others) has been cast aside in Jakarta's recent history. In their engagement with the past and the future through the fragment or debris, these responses invite reflection on what has been lost behind the promise of futural urban projections in the Southeast Asian present and what memories or presences could be reclaimed or reconfigured into other futures during their production.

Forest City showcase, 2016. Photo courtesy of the author.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.