Jewish Mourning Practices Under Lockdown and Quarantine: The COVID Kaddish Conundrum

contributed by Levi Cooper, 17 June 2021

Cover image: Morning prayers, including reading the Torah, conducted outdoors and with masks as per government guidelines. Zur Hadassa, Israel, September 17, 2020. Photograph by Levi Cooper

The Conundrum

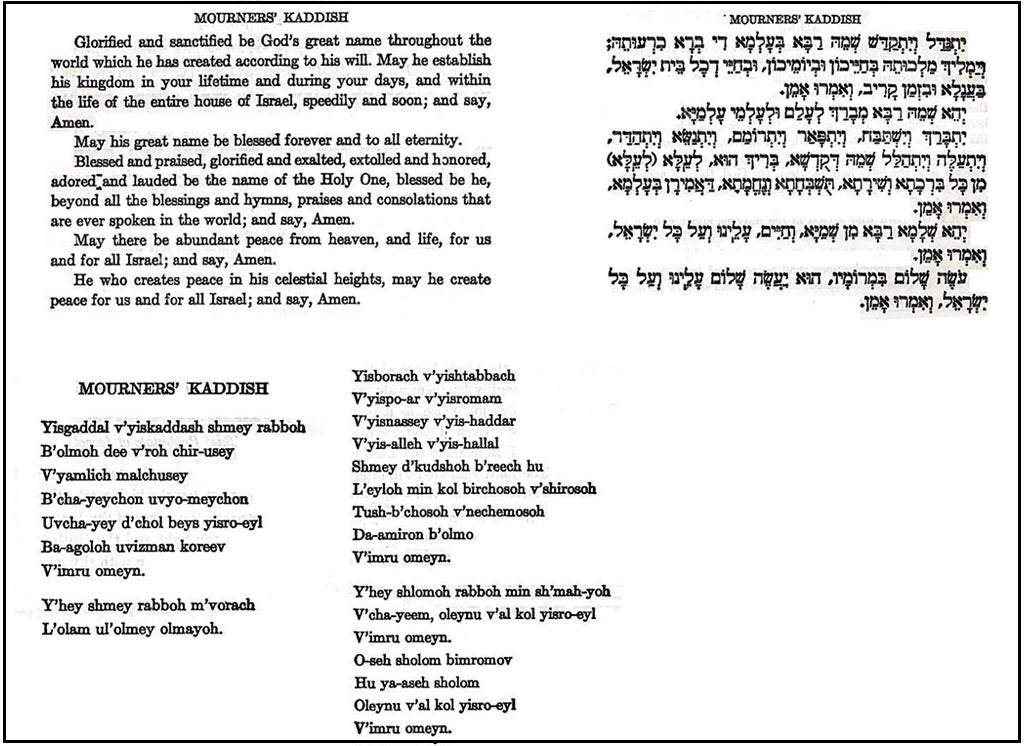

Jewish mourning practices include the recitation of Kaddish (literally: sanctification) – a responsive prayer that affirms God’s greatness (Figure 1). The prayer is a central mourning ritual and is principally recited by children of the deceased. While Kaddish is not a prayer for the dead, it is perceived and experienced as a memorial prayer or a salve for the soul of the departed. The recitation occurs at each of the three daily prayer services, during the prescribed grieving period, and on the recurring anniversary of death. The emotional valence of the encounter gives the ritual additional layers of meaning. Even Jews who are not observant may make the effort to recite Kaddish.

Figure 1. Daily Prayer Book, translated and annotated with an introduction by Philip Birnbaum (New York: Hebrew Publishing Company, 1949), 137-138. The prayer is presented in the original Hebrew and Aramaic, together with a translation and a transliteration for those who have trouble understanding or reading the original text

Kaddish recital is possible where there is a minyan – the presence of a quorum of ten Jews. Quarantines, lockdowns, and other crowd-limiting measures hamper gathering as a quorum. When congregating is forbidden, rituals dependent on the physical presence of a congregation become difficult, if not impossible. Thus, the Coronavirus pandemic gave rise to a Kaddish conundrum.

What solutions for Kaddish reciters have been employed since March 2020? What were the achievements and drawbacks of each solution? My goal is to present a prosopographic account, setting aside the specifics of which solution was advocated by which stream of Judaism or sector of the Jewish community. This methodological approach provides a platform for asking a broad question: What does the quest for solutions tell us about Jewish practice and tradition?

Solutions for the Kaddish conundrum may be divided into two classes: Substitutes and Workarounds.

Substitutes

When gathering was not permitted, some advocated substitutes that obviated the need for a quorum. The goal of such suggestions was to provide mourners with an experience of performing a ritual for the deceased, even if it was not the traditional practice. Kaddish substitutes can be divided into two categories that might be termed Shades and Replacements.

Shades of Kaddish

By Shades I mean prayers that resemble Kaddish, drawing on the themes or even the words of the traditional prayer. There are sources in Jewish tradition for such texts. Thus, for example, Rabbi Dov Baer Edelstein (d. 2018) composed a Hebrew prayer for those unable to attend a prayer service in order to recite Kaddish. This text was disseminated online during the pandemic, together with English translations.

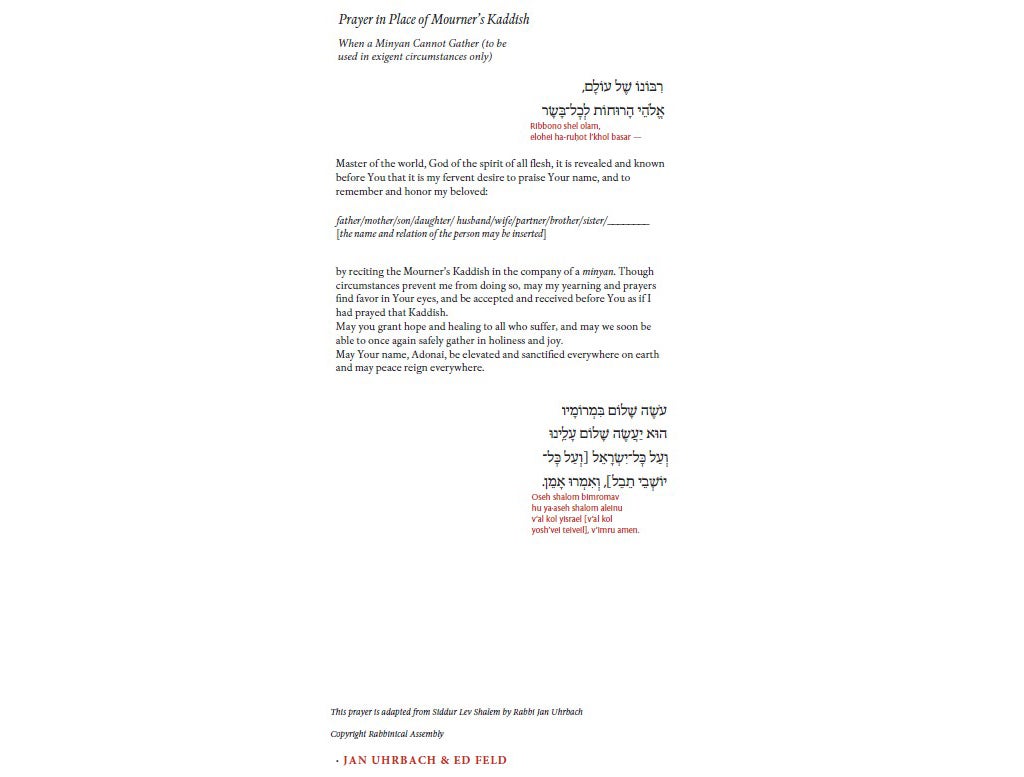

New Shades of Kaddish that had not previously been discussed were also suggested during the current pandemic, such as the Prayer in Place of Mourner’s Kaddish (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Rabbi Jan Uhrbach and Rabbi Ed Feld, Prayer in Place of Mourner’s Kaddish, 13 March 2020, downloaded from the website of the Conservative Movement's Rabbinical Assembly

The opening of this prayer is not drawn from Kaddish, yet the supplicant references the mourner’s prayer and the forum in which it is traditionally recited. When the supplicant says “May Your name, Adonai” – a Hebrew word used to refer to God – “be elevated and sanctified everywhere on earth and may peace reign everywhere,” there are echoes of the first and last lines of Kaddish. The concluding line in Hebrew uses the same line as the Kaddish conclusion, tying the new prayer to the traditional mourner’s prayer.

The bracketed subtitle – “to be used in exigent circumstances only” – indicates a concern lest this substitute becomes the norm and forestalls communal gatherings. In this vein, the authors included a prayer for return to communal settings: “[M]ay we soon be able to once again safely gather in holiness and joy.”

Kaddish Replacements

Another type of substitute could be termed Replacements – acts other than the recital of Kaddish that memorialise the deceased or grant merit to the soul of the departed. These suggestions do not mimic Kaddish, rather they advocate alternative action. Here too, classic Jewish sources provide useful precedents or serve as sources of inspiration.

For example, Rabbi Joseph Yuzpa Han Noirlingen (1570-1637) wrote that it was more important to study Jewish texts than to recite Kaddish. Two centuries later, another hierarchy was offered by Rabbi Solomon Ganzfried (1804-1886):

Even though recital of the Kaddish and the prayers assist the parents, nevertheless they are not the essence. Rather, the essence is that the children should walk in a straight path, because in this they grant merit to the parents.

Two different preference schemes were offered, though both hierarchies did not prioritise Kaddish.

In a public letter issued in March 2020, rabbinic authorities in Sydney advocated a Kaddish replacement in the spirit of these sources (though they did not cite them). The rabbis reminded people that protecting the health of others was of supreme importance, and such caution would give the deceased more spiritual pleasure than recitation of the traditional Kaddish. Moreover, people were encouraged to perform good deeds in honour of the departed.

Despite the existence of precedents, Substitutes have not been championed by rabbis. Indeed, pandemic-related Jewish literature, produced at dizzying speeds and disseminated in electronic form, seldom focused on these sources.

Jewish religious leaders did not offer explanations for why they were not promoting these solutions. It could be that leaders felt that introducing Substitutes would add further disruption to time-honoured rituals at a time when life in general had already been unsettled. It could also be that rabbis were hesitant to suggest Substitutes for fear of their long term consequences: If there were valid Kaddish Substitutes, perhaps they would be preferred beyond the pandemic?

Even when Substitutes were mentioned, they were not embraced by mourners. Shades and Replacements were perceived as rootless or a pale shadow of the real Kaddish experience. The Substitutes did not offer the palliative energy that Kaddish recital in a communal setting has come to provide. Kaddish Substitutes are, therefore, unlikely to impact Jewish practice beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

Workarounds

Another type of solution could be termed Workarounds; that is, circumventing a systemic limitation. The system – in this case the traditional Jewish system of ritual – dictates that Kaddish recital requires the presence of a quorum. Hence a workaround would circumvent one of the ritual’s elements: quorum, recital, or presence. I set aside redefining Kaddish itself, since I included that under the Substitutes rubric and already suggested that they were not embraced. Kaddish itself was non-negotiable, but what of the other elements?

Quorumless Kaddish

One workaround addressed the quorum requirement, arguing that Kaddish could be said without a quorum. The quorum requirement was thus recalibrated as a preferable element of Kaddish recital, but not an essential condition.

Quorumless Kaddish has a precedent in the exigencies of the Second World War, when it was suggested by the United States’ Committee on Army and Navy Religious Activities (CANRA) as a solution for Jewish soldiers and sailors serving in distant locations.

Quorumless Kaddish has been mentioned during the current pandemic, but was not widely touted as a solution due to the following factors:

- From the perspective of Jewish law, it is difficult to identify sources that provide a basis for Kaddish recital without a quorum, and the notion goes against a central element of the mourners’ prayer.

- From the perspective of communal leaders, advocating this route might undercut the notion of mourning as a communal enterprise.

- From the perspective of mourners, the lack of community as represented by the quorum transforms the practice from a communal ritual into private bereavement.

Given that Quorumless Kaddish has not been widely advocated during COVID-19 lockdowns and quarantines, and considering its shaky legal underpinnings, it is unlikely that it will gain traction beyond the pandemic.

Kaddish by Proxy

A second workaround redefines recital, and has been termed Proxy Kaddish. A person other than the mourner is deputised to recite Kaddish for the deceased on behalf of the mourner. This is a recognised rubric that has been employed throughout the ages.

Classic Proxy Kaddish was a service provided for a fee. Subcontracting Kaddish has been criticised when a person is able to recite Kaddish but hires someone else out of convenience. Thus, vicarious Kaddish recital is a legitimate but non-preferred route.

I have yet to find evidence of Proxy Kaddish during previous pandemics, presumably because everyone in the reciter’s vicinity would have been under the same quarantine conditions, and therefore able to participate in a quorum in order to recite Kaddish.

As mentioned, CANRA addressed the Kaddish needs of soldiers and sailors unable to join a quorum. CANRA first recommended Quorumless Kaddish, before offering a Proxy Kaddish service.

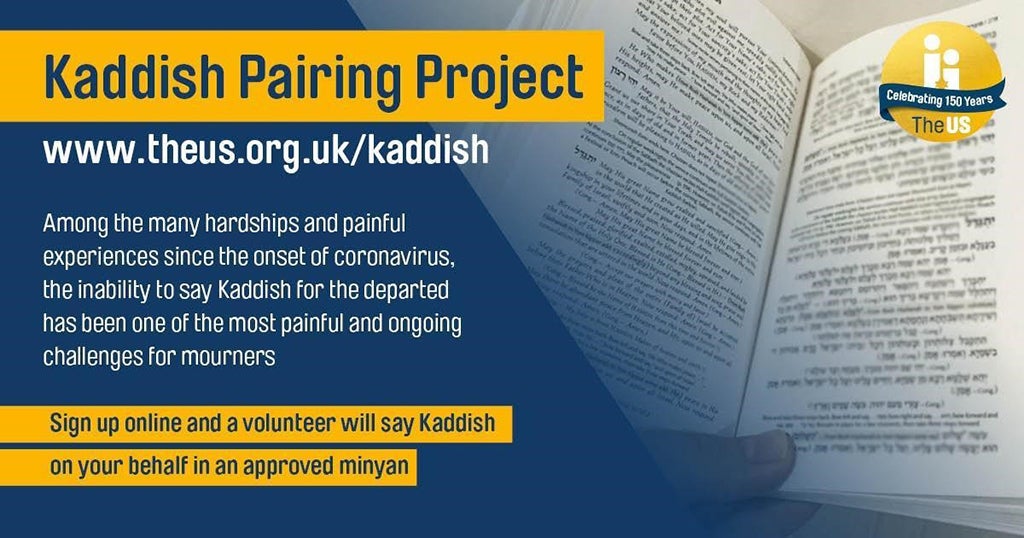

Modern telecommunication facilitates the possibility of reaching someone in a distant land to ask them to recite Kaddish. The internet has expanded this possibility. Thus communities offered such services via internet portals, when synagogues were open but individuals quarantined (Figure 3). Organisations with branches around the globe offered Proxy Kaddish services when all local prayer gatherings were denied.

Figure 3. Kaddish Pairing Project, a free service offered by the United Synagogue in Britain

It is doubtful that we will see a change in Jewish ritual due to pandemic-related Proxy Kaddish. First, Jewish tradition has deemed it preferable that the mourner recite Kaddish, not a subcontractor. Second, subcontracting Kaddish has been employed in non-pandemic conditions, and internet-based Proxy Kaddish existed before the Coronavirus outbreak. There is no reason to assume that the present pandemic will result in a post-pandemic increase in the use of this service. Third, Proxy Kaddish does not answer personal bereavement needs. The mechanism solves the desire to pray on behalf of the deceased, but it does not address the mourner’s grieving process. Thus we can expect subcontracting Kaddish to continue as it did before COVID-19, and it is unlikely that the pandemic will affect its prevalence.

Virtual Quorum

A third workaround challenged the notion of presence: A quorum was required, as was recital by the mourner, but presence was redefined as virtual presence.

Virtual Quorums have clear advantages: the mourner has the personal experience of reciting Kaddish within a communal setting. The solution taps into the shift in human interaction during the pandemic to solve the Kaddish conundrum. In various places, while COVID-19 was raging, going to work or school was defined by virtual presence; that is, logging on without leaving your home. Similarly, going to synagogue and participating in a prayer service was defined by virtual presence. This route was part of a group of virtual solutions that have come into play during the pandemic.

Virtual Quorums reflect the mourner’s need to recite Kaddish. The preference for a virtual gathering rather than a private recital demonstrates the need for community. Kaddish is not just about the individual’s private bereavement journey, it also bespeaks communal support for the mourner during the Kaddish period. Anyone who opted for Kaddish in a Virtual Quorum was broadcasting a need for a communal embrace.

However, Virtual Quorums raise long-term questions: To what extent will this novelty survive the pandemic? In the future, Virtual Quorums could provide opportunities for those who are immobile or do not live near a Jewish community. Yet this option could be a double-edged sword. Will those who are able to attend a synagogue make the effort if they can recite Kaddish from their own homes?

Implications

The taxonomy that I have sketched constitutes a frame for considering how individuals and communities have coped with the COVID-19 Kaddish conundrum. The map tells a story about the contemporary Judaism and its approach to tradition and ritual:

- The solutions drew on existing – though often neglected – textual sources. This is emblematic of the ongoing evolution of Jewish tradition; a heritage steeped in text. The image that emerges from the array of solutions is that there exists a trove of rich sources lying dormant. These slumbering resources hibernate until such time as they are called upon by the community.

- Jewish ritual practice may not be as frozen in time as many had thought prior to the pandemic. Perhaps inertia and the gravitational pull of preservation over innovation kept existing rituals in orbit. Yet our world has been shaken like a snow globe: Particles flying in all directions, and what appeared to have been settled is suddenly in a chaotic swirl. As the shaking stops, the particles are left in suspension as they gradually float back down to ground. It is unclear where these flakes will land. The final chapter of the tale of COVID-19 Kaddish has yet to be written.

- Despite the plethora of possibilities, contemporary Jewry has anonymously and unconsciously declared that rituals like Kaddish must continue. Simply put: Mourners want to recite Kaddish in a communal setting, even when a pandemic is raging.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the blog editorial team or the Asia Research Institute.

South Asia | Southeast Asia | East Asia | Other Places | Hinduism | Buddhism | Islam | Christianity | Other Religions

Levi Cooper, originally from Melbourne, teaches at the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies and in Tel Aviv University’s Law Faculty. His research focuses on interplays between Jewish legal writing and broader legal, historical, intellectual, and cultural contexts. Levi’s book, Relics for the Present, offers a contemporary commentary on the Talmud.

Other Interesting Topics

Countering Violent Extremism Online: Global Best Practices and Potential for Implementation in Bangladesh

Although terror attacks have existed since time immemorial, the September 11 attacks in New York marked a new chapter. It was a chilling reminder of the potency of violent extremism (VE) as we woke up to the existence of international terror networks...

The Sonic and the Somatic: Matua Healing Practices during COVID-19

The disturbing times of COVID-19 have impacted the relatively unknown Matua religion and its devotees, especially their healing practices. As a religious and social movement suffering social wounds such as untouchability and displacement, the Matuas have historically deployed strategies of healing, not only in the medical sense of the term, but also within the framework of social upliftment...

The Cap Go Meh that Never Happened (2)

On February 21, 2021, the final meeting between the Singkawang city government and the religious councils was planned regarding the holding of Cap Go Meh this year marked by the global COVID-19 pandemic. That meeting was postponed to February 22, because the mayor had to go to Jakarta to receive an award from the Setara Institute...