A decolonial past: Raden Odjoh Ardiwinata and the study of Indonesia’s freshwater fishes

Freshwater fishes abound in Indonesia. They are everywhere in the archipelago—from urban drains, rice fields, and irrigation canals to park ponds, brackish lagoons, and highland rivers. They even populate the most unassuming bodies of water. Some species are found in the remotest of volcanic lakes while others call the blackest and most acidic peat swamps their home. Every island has its aquatic habitats and every one of these habitats has its fishes, making Indonesia one of the world’s richest centres of ichthyofaunal diversity.

![Figure 1 Figure 1. ‘A caught sawfish [Pristis spp., marine/coastal species but also known to swim in estuaries and rivers] is hoisted onto the wharf (1930).’ Source: Leiden University Libraries, Digital Collections, Southeast Asian and Caribbean (KITLV) Images, KITLV 32841.](https://ari.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Figure-1.png)

It is this unrivalled scale of biodiversity that offers something new for Indonesian studies and the wider field of Southeast Asian history. Ichthyologically, for example, the archipelago is second in the world, after Brazil, with regard to freshwater fish diversity. As for species density (the number of freshwater fish species per 1000 km2), Indonesia tops the global list. And while Asia is the site of some 3,500 recorded freshwater fish species, nearly a third of these fishes are found within the islands of the archipelago like in Sumatra, Java, and Borneo, and more than half of them are endemic to the country’s freshwaters.

One of these endemic species looms larger than others: the Paedocypris progenetica. Described by a team that includes Heok Hui Tan of Singapore’s Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum in 2005, this endemic fish is not only restricted to the peat swamps and blackwater streams of Jambi and Bintan, it is also the world’s smallest known vertebrate species. Dynamic, unique, exceptional, and rare, Indonesia’s freshwater biodiversity is ecologically rich and of great cultural-historical value.

But we also know that Indonesia’s freshwater biodiversity is under threat from a variety of anthropogenic forces. Development and infrastructure are reshaping the archipelago in far-reaching ways. Dams, highways, mines, logging, industrial agriculture (palm oil expansion), urban sprawl, and other land-use changes have impacted the country’s natural habitats in the form of fragmentation and degradation to outright losses.

A recent comprehensive analysis of dams and their impacts on freshwater fishes determined that hydropower schemes were one of the greatest threats to global ichthyofauna diversity because they fragmented habitats and thus disrupted river connectivities and critical life cycles.

While our knowledge of Indonesia’s freshwater biodiversity is attentive to all kinds of matters that animate the present, from faunal richness and species loss to habitat changes and eutrophic lakes, it is also grounded in the past. A history of biodiversity research has shaped our understanding of Indonesia’s freshwaters and the wonders and worries that lurk within them.

It is without question, however, that the culinary worlds of the archipelago have profoundly contributed to what we know about Indonesia’s freshwater biodiversity too. Fish and water have been, and remain, at the heart of everyday life for most people. But the story of Indonesian scientists plays an integral part in the formation of our knowledge as well.

One Indonesian scientist who stands out among the many who researched and popularised freshwater fishes is Raden Odjoh Ardiwinata (1896-1967). Born in Ciamis, West Java, Ardiwinata studied at the Middlebare Landbouwschool in Buitenzorg before joining its Department of Economic Affairs in 1916.

For more than a decade, Ardiwinata progressed within the Department’s division of agriculture. In 1929, he was promoted to a new position, serving as the only Indonesian agricultural teacher at the Normaalschool for Indonesian Assistants in Garoet. In 1931, Ardiwinata was appointed to the Regency Council van Buitenzorg.

Yet missing from Ardiwinata’s agricultural work and his time on the regency council were freshwater fishes. That changed in 1935, when he moved to Bandoeng and joined the Department’s division for inland fisheries. Ardiwinata’s move to the division for inland fisheries transformed not only the arc and nature of his career but also, more broadly, the life and legacy of fish research in the archipelago.

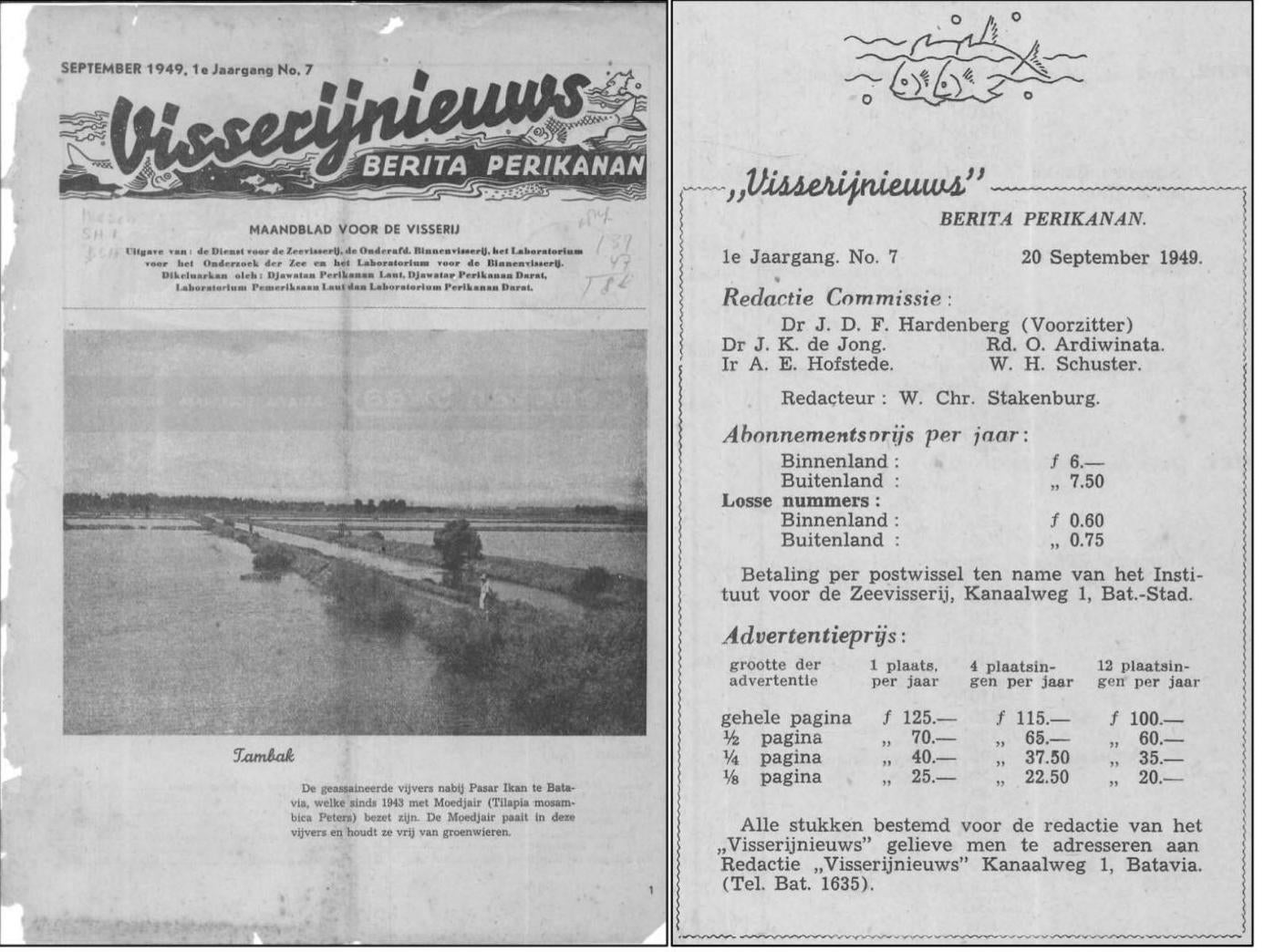

From the 1930s to the 1960s, fishes became the centre of Ardiwinata’s world. Initially an Adjunct Visscherijconsulent in Bandoeng in 1935, in 1949 he became the first Indonesian appointed to head the Department’s division for inland fisheries.[1] In collaboration with his Dutch colleagues who directed the division for sea fisheries, the laboratory for the investigation of the sea, and the laboratory for inland fisheries, Ardiwinata launched and edited the monthly magazine Berita Perikanan.

Published out of Jakarta by the division of agriculture from 1949 to 1962, Berita Perikanan was a popular platform that shared details about edible species, fishing methods, and robust areas of decolonial research such as documenting the vernacular taxonomies of Indonesia’s ichthyofauna. Ardiwinata was at the forefront of creating national space for local scientific knowledge production.

In the September 1949 issue, for example, he provided a checklist of Sundanese names for some of the different kinds of freshwater fry found in West Java’s Priangan district.[2] Berita Perikanan also captured news and developments that extended beyond the work of the Department. In 1953, the editorial committee reported the founding of Masyarakat Perikanan Indonesia and Ardiwinata’s election as the first “ketua” or chairman of this national organisation of fishers, scientists, and technologists.[3]

Ardiwinata’s growing career also shaped the expanding study of Indonesia’s ichthyofauna. In particular, his popular writings about food fishes—and the threats to them—fostered widespread public interest in the ecology and economy of the country’s freshwater systems.

In 1950, for instance, he authored a little pamphlet about the “dangers” of elong-elong (Eichnornia cressipes, water hyacinths) and how the invasiveness and abundance of this alien plant (native to the Amazon basin) posed a risk to the ichthyofauna of Rawa Pening.[4]

Ardiwinata’s research in effect documented the slow violence of eutrophication and how it contributed to the “overgrowth” of elong-elong that choked the fish life out of one of central Java’s most important freshwater lakes.[5]

The study of Indonesia’s freshwater biodiversity—and in particular its fishes, lakes, and rivers—gained new urgency in the 1950s, with matters of population and provision figuring at the heart of national development. Ardiwinata was crucial to this period of local scientific knowledge production.

By 1952, for example, he was no longer administering the division for inland fisheries but rather directing the newly-established Balai Penjelidikan Perikanan Darat (Inland Fisheries Research Institute) from its headquarters in Bogor (Buitenzorg). As head of the institute, Ardiwinata was in charge of overseeing research that was borne out of a need for popular knowledge about Indonesia’s freshwater fishes and habitats and the ways in which this knowledge could be extended to the public during “this era of massive development.”[6]

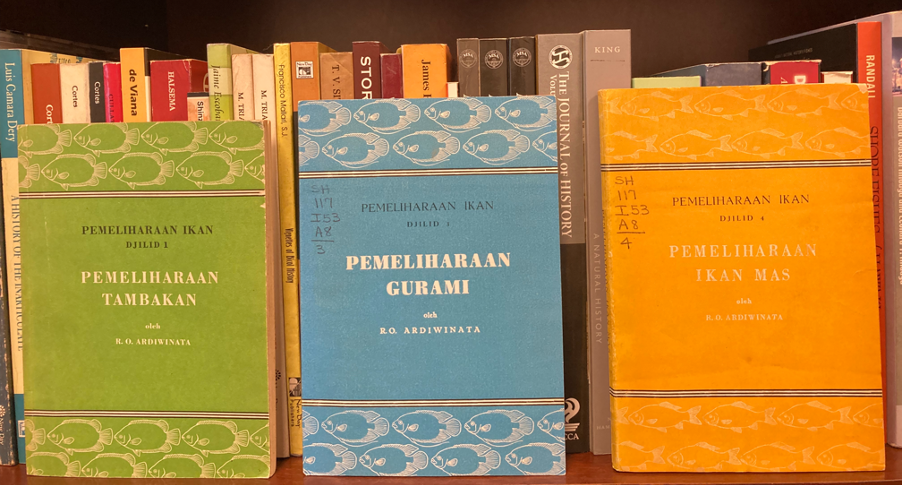

At the same time, Ardiwinata was also authoring what he called “buku-buku ketjil” or little books, or a series of species biographies of Indonesia’s important ichthyofauna.[7]

Collectively, these little books provided useful information about the ecological, scientific, and economic life of some of Indonesia’s key food fishes. On tambakan (Kissing gourami, Helostoma temmincki Cuvier, 1829), for example, we learn that this fish was first sourced from the swamps around Palembang in the late nineteenth century and introduced to other regions in the archipelago such Java and Kalimantan.[8] And based on the research of scientists at Balai Penjelidikan Perikanan Darat, we also learn about the different kinds of plankton that tambakan consumed—from the names and colours of these plankton to what they looked like under a microscope.

Through Ardiwinata’s scientific life, we can see how thinking with fish opens up new ways of knowing the story of Indonesia’s freshwater biodiversity. While his career and expertise reflect a body of local environmental scholarship, they also bring to light a decolonial archive replete with data about the country’s ichthyofauna. From fry names and fish biographies to alien plants and plankton types, histories of local scientific knowledge production run through the archipelago in ways that offer new directions and opportunities for Indonesian studies and the wider field of Southeast Asian history.

Resurfacing these pasts, making them known, and incorporating their details into the archipelago’s biodiversity narratives is just one example of how the work and legacy of Ardiwinata can serve to seed new grounds for knowing Indonesia’s freshwater history.

[1] On Ardiwinata’s appointment as head of the division for inland fisheries, see Bulletin No. 6 van de Onderafdeling Binnenvisserij van het Departement van Landbouw en Visserij (Buitenzorg: Departement van Landbouw en Visserij, 1949).

[2] “Nama-nama Sunda dari matjam-matjam benih ikan di Priangan,” Visscherijnieuws/Berita Perikanan 1, 7 (September 1949): 10.

[3] “Fisheries Society of Indonesia,” Berita Perikanan 5, 4-5 (June-July 1953): 77.

[4] “Kantor urusan Perikanan Darat,” Berita Perikanan 2, 9 (November 1950): 133.

[5] “Kantor urusan Perikanan Darat,” Berita Perikanan 2, 9 (November 1950): 133.

[6] Raden Odjoh Ardiwinata, Pemeliharaan Tambakan: (Biawan) (Bandung: W. van Hoeve, 1955), 4. This publication was originally published in 1952.

[7] Ardiwinata, Pemeliharaan Tambakan, 5.

[8] Ardiwinata, Pemeliharaan Tambakan, 7.

Copies of Berita Perikanan are kept in the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute Library in Singapore and remain a rich source of data for scholars looking to bring the wealth of fish, expertise, and ecology to Indonesian history and the broader field of Southeast Asian environmental humanities. I am indebted to Anastasia Kurniadi, an undergraduate at Yale-NUS College and one of my student researchers, for securing these materials for me to use.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.