Picturing the past: Postcards and the pre-war Japanese in Singapore

https://doi.org/10.25542/exc0-g9mp

Histories of the Japanese presence in Singapore usually focus on the period of the occupation from 1942-1945. However, the Japanese had been visiting or living in Singapore since the late-19th century. The first documented Japanese resident, Yamamoto Otokichi (also known as John Matthew Ottoson, 1818-1867), arrived in 1862. By 1881, there was a small population of 22 Japanese living in Singapore. This number grew exponentially to 1,215 individuals by 1910.

Little is known about this pre-war community of Japanese migrants, and census data provide only a limited window in their lives. How did they build a community for themselves? Where did they set up shop? What customs did they continue in Singapore and what did they adopt from local communities? The dearth of surviving sources from the pre-war Japanese community has made it difficult to answer these questions.

Apart from local Japanese residents, Singapore’s status as a port-of-call for major shipping routes to Europe also meant that many Japanese travellers took the opportunity to go on short local tours when the ship pulled into Singapore. What did these early Japanese visitors see when they first arrived in Singapore? What did they write to their friends and family?

A new book, Postcard Impressions of Early 20th Century Singapore: Perspectives from the Japanese Community (Singapore: National Library Board, 2020)—jointly authored by me, Ling Xi Min and Naoko Shimazu—represents an endeavour to answer these questions using postcards. As historical sources, postcards reveal travellers’ impressions and local Japanese residents’ experiences in two ways: in their written messages and the images (on the postcards) they chose to accompany these messages.

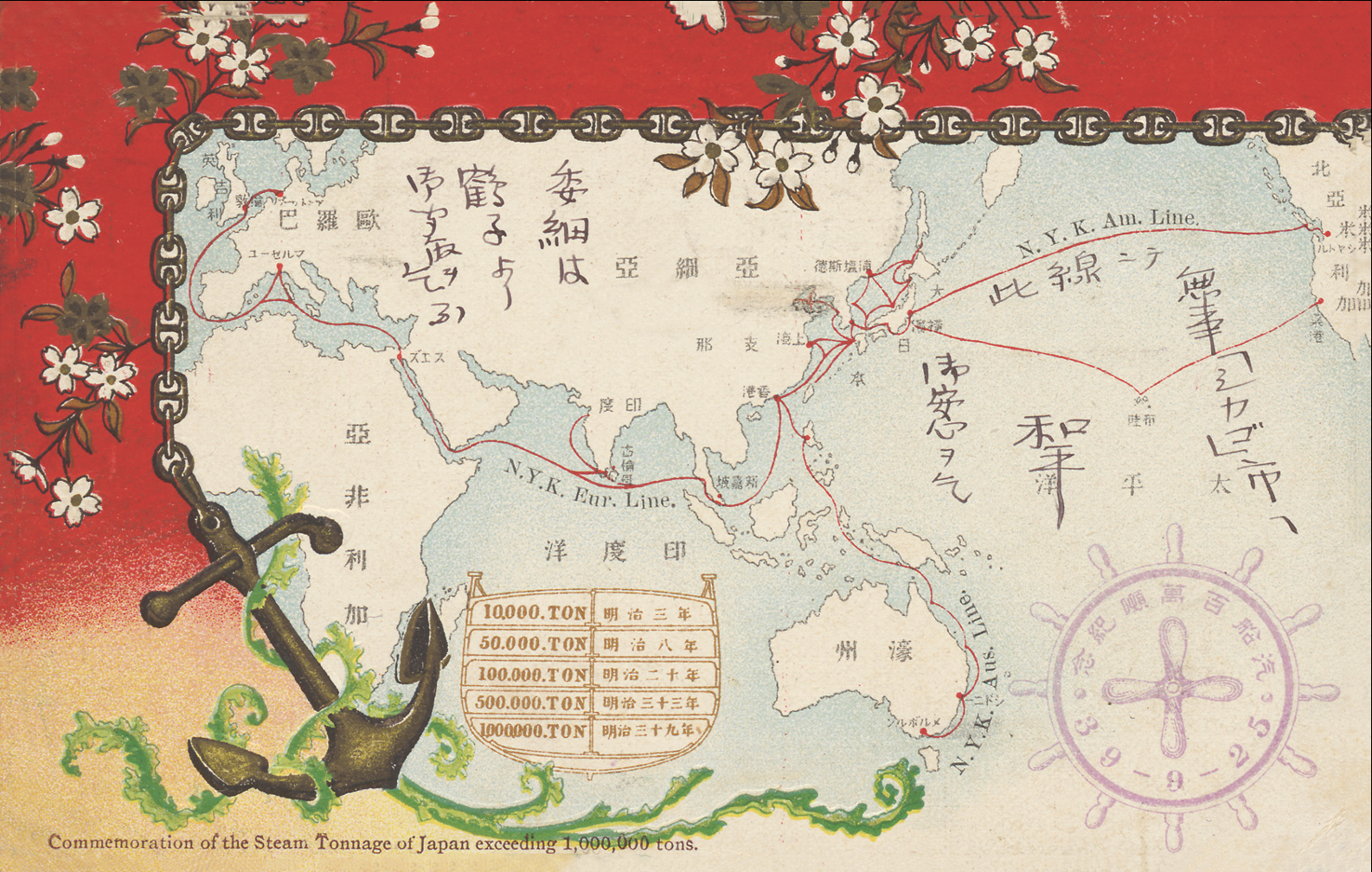

The textual and visual nature of postcards make them adaptable for purposes other than correspondence. For example, they were also given out as commemorative souvenirs to visiting naval training fleets and were used by travellers to take notes on the sights they had seen. These functions, in turn, give more insight into the activities that travellers and local Japanese residents undertook in Singapore.

Such research would have been impossible without the invaluable postcard collection of Mr Lim Shao Bin, donated to the National Library Board of Singapore (NLB) between 2016-2017 for research purposes and to educate younger Singaporeans about the history of the Second World War. Apart from the postcards, Lim’s donation also includes books, letters, atlases, photographs and materials related to Japan’s military campaign in Southeast Asia, such as wartime maps and newspapers detailing the campaign in Singapore and Malaya.

Previously, Lim also published his own book, Images of Singapore: From the Japanese Perspective, 1868-1941 (Singapore, 2004) based on postcards and other visual materials from his large collection. Postcard Impressions of Early 20th Century Singapore builds on Lim’s work, reading postcards to unearth the experiences of Singapore and the pre-war Japanese community from over a hundred years ago.

Postcards as greeting ‘cards’

Nengajō, or Japanese New Year greeting postcards, have a long history and are still popular in Japan today. The practice of exchanging written New Year greetings was present in Japan as early as in the Heian period (794-1185), but it was only around 1887, after the development of the modern postal delivery system, that sending nengajō became widespread.

Nowadays, post offices issue postcards with beautiful designs for this purpose, although individuals sometimes make their own nengajō designs by carving auspicious images and patterns on to raw potatoes, and using them as printing blocks known as imoban (potato printing block) on plain postcards.[1] As long as the cards are mailed by a certain cut-off time, recipients can look forward to the prospect of receiving a bundle of postcards on New Year’s Day.

This custom of sending nengajō persisted beyond the shores of Japan among the pre-war diaspora in Singapore. It was a pleasant surprise to notice that the greetings we saw in Lim’s donated postcard collection were similar to those used in contemporary nengajō. Some of the nengajō in the collection carry only simple New Year greetings while others included more details on their experiences away from Japan. Nor were nengajō the only New Year custom continued in Singapore, as the following postcard indicates. A Japanese writer mentioned that the first shrine visit of the year (hatsumōde), when individuals head to a shrine to pray for good luck for the New Year, had been ‘worse than usual’, suggesting hatsumōde was another tradition carried out amongst the Japanese diaspora in the Straits Settlements (Figure 6).

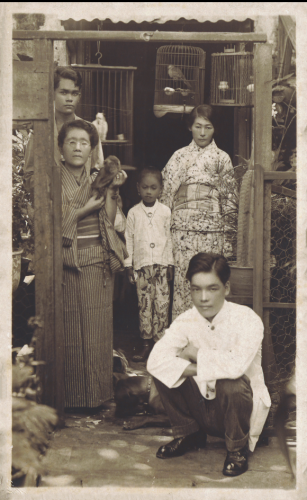

Nengajō also connected Japanese communities across Southeast Asia. One of the authors’ favourite postcards (Figure 7) was sent from an individual living in Malacca to a Mr Shimaya in Singapore. The image on the postcard is particularly intriguing for offering us a ‘hidden’ window into the sender’s family and social circumstances.

The photograph features five individuals surrounded by bird cages in the background. Of note are the individuals’ dress, which give an insight into how the family put their own unique spin on a nengajō by having individuals don other forms of dress in addition to traditional Japanese dress. The two adult women are dressed in traditional kimono while the young girl is dressed in sarong kebaya (a traditional dress worn by women in Indonesia and some parts of Southeast Asia). The man squatting in the foreground is dressed in a shirt with a mandarin collar and pants. The caged birds in the background and the monkey in the older adult woman’s hands appear to be family pets. Although the message on the postcard mainly consists of the standard New Year greetings, the personalised photo on the postcard gives us an insight into the individual who wrote the postcard. Because of the popularity of postcards, they can offer insights into a bygone era.

Postcards as Visual Documentation

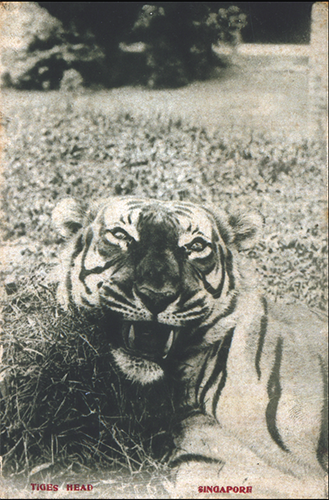

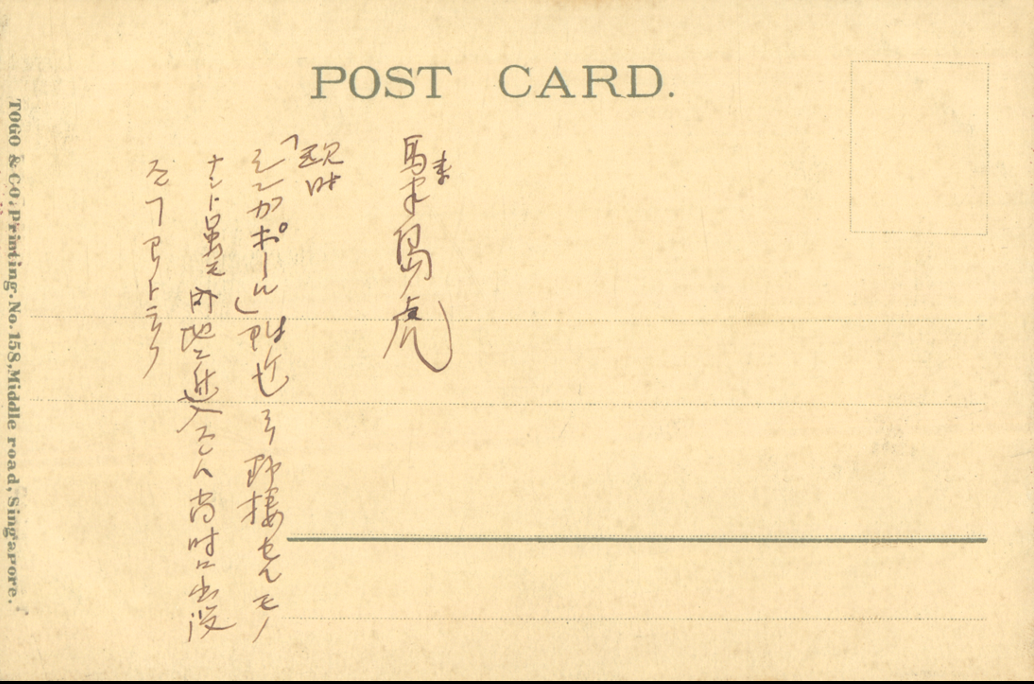

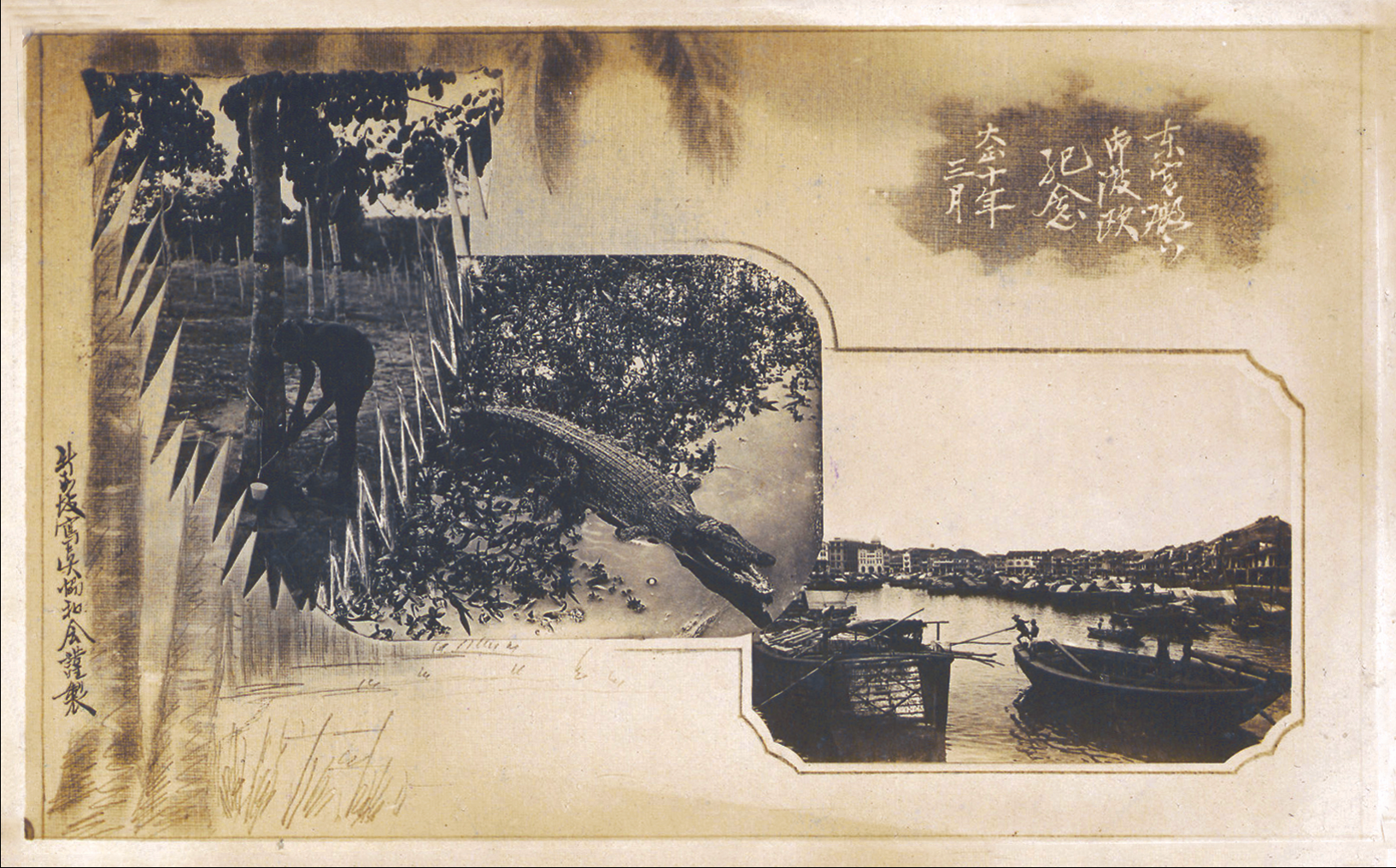

Given that postcards feature both an image and a space on the back for recording writings, some individuals found ways to adapt them for purposes beyond mere correspondence. Some postcards were used as visual documentation of places of interest, as well as of exotic flora and fauna in Singapore. For instance, this postcard features an image of a tiger’s head with notes on the back explaining that it was a Malayan tiger which often appeared in Singapore. As the postcard does not bear a postmark, it is likely that the image and notes on the back were for the owner’s personal use (Figures 8 and 9).

Postcards as promotional material

Another creative use of postcards was their distribution as commemorative souvenirs, whether on the occasion of visiting Japanese naval fleets to Singapore or that of visiting royalty. One key difference was that postcards for the latter were specially commissioned for the occasion while the former was not.

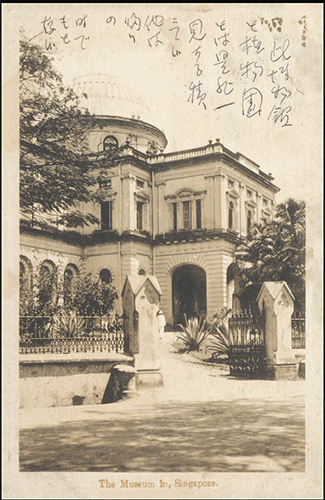

Postcards gifted to visiting naval fleets appear to have been ordinary picture postcards inked with special commemorative stamps to indicate the event. Whether they were specially commissioned or not, postcards for such occasions invariably bore images of iconic architecture and tropical scenes to highlight the particular charms of Singapore (Figure 10).

Something as seemingly mundane as postcards can provide fascinating insights into the Japanese community in pre-war Singapore. Our research revealed how postcards were used for various purposes, be they the nengajō’s conveying of typical Japanese New Year greetings, or the more factual recording of newly found knowledge of the places, animals and plants of Singapore. Apart from their historical significance, these postcards also remind us of our drive to communicate and share our experiences. Whether such communication takes the form of a text message sent through WhatsApp or a postcard carefully selected for its image, each medium is a reminder of the connections that hold a community together.

Regina Hong is Visual Repository Project Coordinator for the Living with COVID in Southeast Asia project at ARI and graduate student pursuing her MA in Digital Humanities at Loyola University Chicago.

[1] Naoko Shimazu’s recollection of her childhood in Japan. Its enduring popularity can be seen by the number of YouTube videos on how to create one.

The views expressed in this forum are those of the individual authors and do not represent the views of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, or the institutions to which the authors are attached.

![postcard-impressions-cover Postcard Impressions of Early 20th-Century Singapore: Perspectives from the Japanese Community. By Regina Hong, Xi Min Ling and Naoko Shimazu. Published by the National Library Board [2020].](https://ari.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/postcard-impressions-cover-300x283.jpg)