Technocratic Deliberation and Asian Peace

By Parag Khanna

Dr Parag Khanna is the founder and managing partner of FutureMap, and author of numerous books including Connectography and The Future Is Asian.

Republished in the Straits Times: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/south-china-sea-claims-technocratic-way-to-peace-0

OCTOBER, 28, 2021

After 30 years of post-Cold War great power stability, Asia’s peace is threatening to unravel. Tensions are rising over Taiwan, the Senkaku islands, and North Korea--all amidst talk of a “new Cold War” between the US and China.

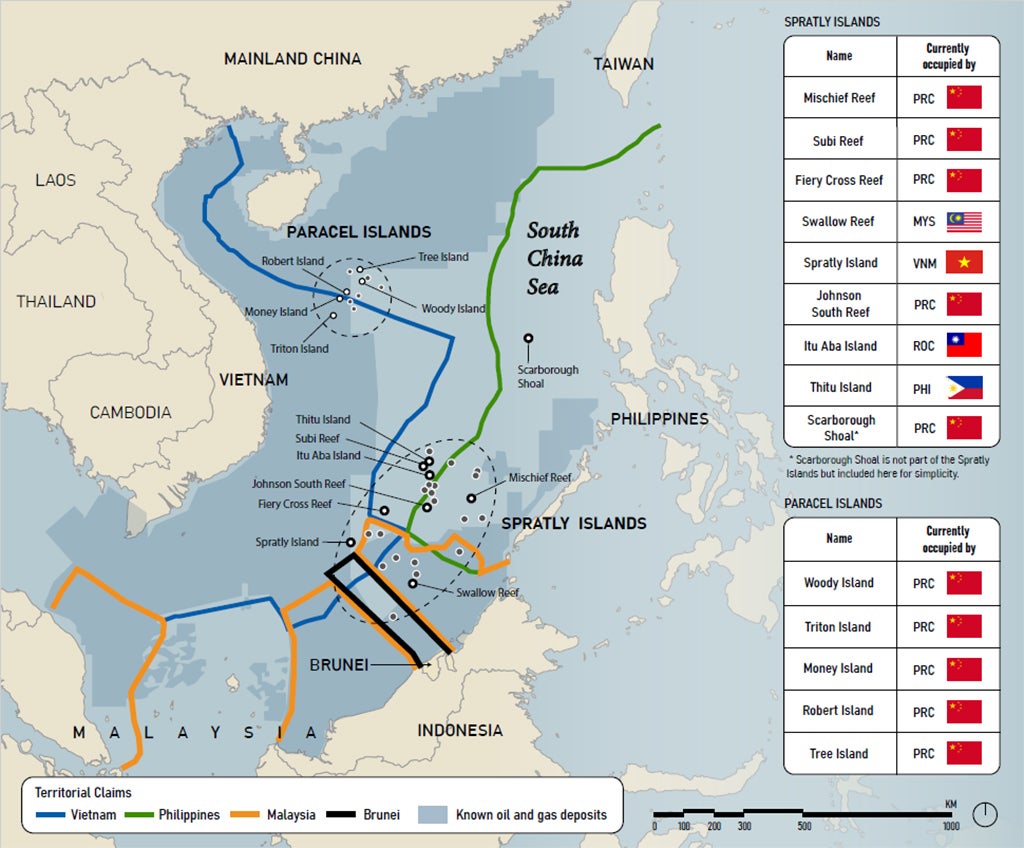

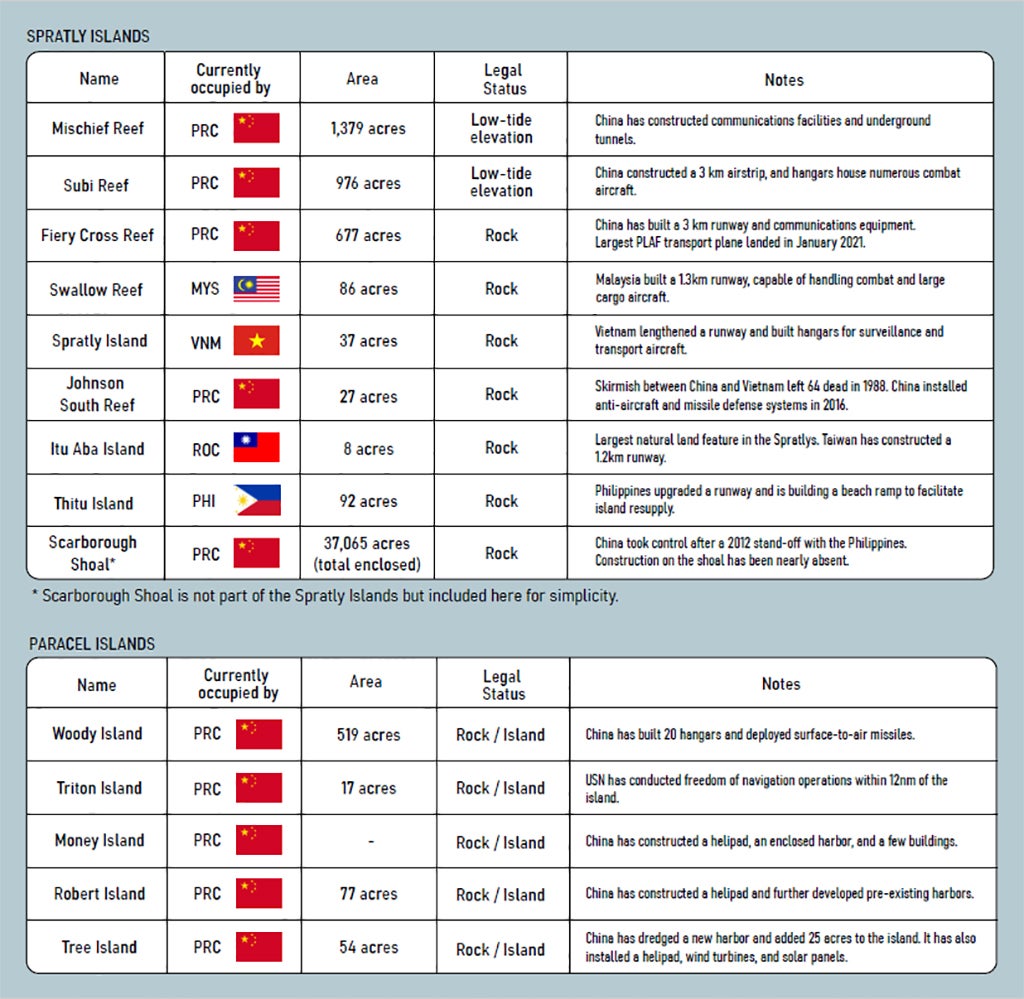

Furthermore, five years have passed since the World Court ruling against China’s claims to a handful of islands in the South China Sea, though to little effect. Beijing rejected the judgment, while the Philippines chose not to take further action for fear of threatening its relationship with its biggest trading partner. Even in the absence of decisive action, military forces are on hair-trigger alert, with numerous close encounters between military warships and aircraft. China has reclaimed and militarised various rocks and reefs, Vietnam is now doing the same, the US and European navies are conducting freedom of navigation operations, and the US, Japan, and India are supporting the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia to build their maritime capacity. The outlook is grave, and some predict that this dispute will spark a Third World War.

Dynamics in the South China Sea are a reminder that Asians have not yet developed sufficiently robust dispute resolution mechanisms to keep conflicts from boiling over. Past success in staving off war does not guarantee future stability: Asia’s evolution into a mature system is far from assured. From the Caucasus to the Himalayas to the South China Sea, there is ample evidence that “frozen” conflicts are nothing of the sort. Until they are settled, they are a latent casus belli. To move beyond today’s dangerous escalations, Asia must do more than tactically suppress historical tensions. Intractable territorial disputes should not stop Asian nations from pursuing pragmatic, mutually-beneficial cooperation in the short term. Pursuing greater cooperation between nation states could eventually push them towards an amicable resolution of territorial disputes.

Asia requires its own version of the prevalent Western paradigm known as “Democratic Peace Theory”. An approach more suited to Asia might be what I call “Technocratic Peace Theory.” Less a predictive hypothesis than a vision for how Asia could handle its ongoing disputes, it suggests that expert arbitration is the approach to permanent dispute resolution best suited to the region’s heterogeneous landscape.

An important virtue of a technocratic approach is that it is not biased towards legal conventions or frameworks not all parties view as legitimate. In the South China Sea, maritime demarcations have their origins in late 19th and early 20th century colonial-era conventions, whereas records show that Chinese and Southeast Asian sailors have travelled, fished, and traded in the region for over 3000 years. These conflicts, then, are effectively pre-legal with respect to contemporary international law. Until sovereignty is settled, the law of nations cannot apply. Western diplomats often speak of the need for a rules-based international order, but in many of these conflict formations, the rules have yet to be agreed in the first place.

Technocratic deliberations over outstanding boundary disputes must involve credible senior representatives from disputant parties authorized to make binding decisions. Their autonomy— even their anonymity— is essential to ensuring the consensus nature of outcomes. Neutral international mediators can also play important roles in building consensus and certifying that agreements are considered formal on all parties. The confidentiality of the proceedings is equally important. Deliberations should be held away from public scrutiny, even though the public may be aware they are occurring. This is essential so that representatives can pursue bold compromises rather than defaulting to political expediency.

This is not to say there is no role for politicians or the public. To the contrary, as parties come close to settlement, parliamentarians and other national political figures can be briefed on the contours of the agreement to prepare to sell it at home. The same applies to leaders themselves, who will be able to claim certain victories and point to others’ concessions.

As exclusive control over the waters of the South China Sea becomes ever less likely, China has shown itself to be open to compromise. In 2019, Xi Jinping offered Philippines president Duterte the possibility of joint oil and gas exploration in the disputed waters, with 60 percent of the profits going to the Philippines in exchange for the latter giving up on its claims to islands China has already seized. While no doubt unfair from a legal standpoint, such a deal would have been a recognition of reality while opening up a new and mutually beneficial chapter in Sino-Philippines commercial relations and a marked contribution to calming the waters.

Ultimately, the deal was not politically viable as a result of having been unilaterally proposed. However, a deal to this effect could be negotiated by the relevant parties through a robust diplomatic mechanism, dividing the profits of oil and gas exploration, limiting overfishing, and agreeing to share exclusive economic zones. This would resolve the issues in a way which would enable leaders to claim certain victories and point to others’ concessions, thus providing the legitimacy required for the treaties to be ratified domestically. Furthermore, such a structure could apply to multiple claimant states, not just bilaterally.

Realistically, technocratic deliberation is the key to deescalation within the region. Settlement now, facilitated by the technocratic governance of the parties involved, is preferable to uncontrolled escalation later. Asian nations have been pragmatic about their disputes for several decades, and all have benefited enormously from regional stability. Today, they face a choice between resolving the South China Sea dispute in a mutually profitable manner versus potentially sparking a war that draws in major military powers. If Asia wants to demonstrate its capacity for global leadership, it must start by calming its own waters.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Latest

Safer Together: Why South and Southeast Asia Must Cooperate to Prevent a New Cold War in Asia

Sarang Shidore

Freeze, Talk and Trade: the 3 Principles of Peace

Kishore Mahbubani

China and India: More New Diplomacy

Kumar Ramakrishna

Countering the threat of Islamist extremism in Southeast Asia

Kumar Ramakrishna

Asia, say no to Nato: The Pacific has no need of the destructive militaristic culture of the Atlantic alliance

Kishore Mahbubani

Can Biden bring peace to Southeast Asia?

Dino Djalal

An India-Pakistan ceasefire that can stick

Ameya Kilara

An antidote against narrow nationalism? Why regional history matters

Farish A Noor

The Anchorage Meeting Will Buy America Needed Time

Douglas Paal

The oxygen of ASEAN

Kishore Mahbubani

Beware of Munich

Khong Yuen Foong

Can South Asia put India-Pakistan hostilities behind to unite for greater good?

Ramesh Thakur

Nuclear Deterrence 3.0

Rakesh Sood

The Biden era: challenges and opportunities for Southeast Asia

Michael Vatikiotis

Islamist Terrorism in Indonesia: Roots and Responses

Noor Huda Ismail

Can Asians speak truth to power?

Hugh White

How China and the U.S. Can Avoid a Clash in the South China Sea.

Mark J. Valencia

China and Japan: Will They Ever Reconcile?

Tommy Koh

China and India: A New Diplomacy

Kanti Bajpai