Civilisational Futures and the Role of Southeast Asia

By Tim Winter

Professor Tim Winter is Senior Research Fellow at the Asia Research Institute, NUS. He was previously Professor and Australian Research Council Future Fellow at the University of Western Australia, and is author of Geocultural Power: China’s Quest to Revive the Silk Roads for the 21st Century and The Silk Road: connecting histories and futures.

Republished in The Straits Times: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/south-east-asia-s-role-in-a-future-of-civilisational-states/

SEPTEMBER, 8, 2023

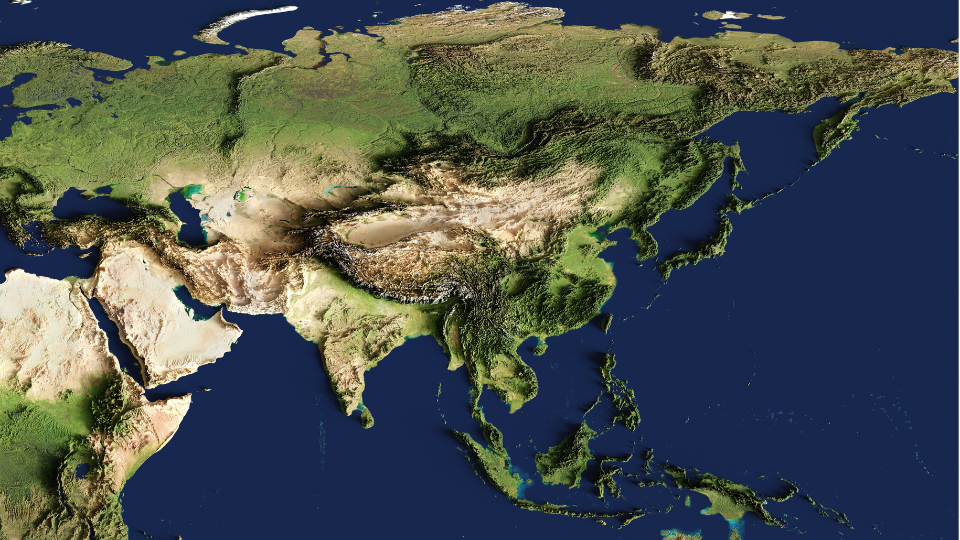

Civilisation has once again become a key term of international affairs. China, India, and Turkey are among those that have invoked the idea of the civilisational state to proclaim they hold the values required for 21st Century internationalism, and its leadership. US-China rivalry and the expansion of BRICS also speak of an emerging East-West divide, one that is, in large part, cast in civilisational terms. Civilisation is now becoming a key marker of difference at a time of increasing geoeconomic competition and political tension.

Broadly speaking, civilisations are most commonly imagined as historical-cultural zones that can be depicted as regions on maps with historical borders, capitals and frontiers. In the modern era, states have often claimed a civilisational legacy by identifying a spatial continuity between past and present, often in nationalistic and jingoistic ways. But in South-east Asia, ideas about civilisational pasts and kingdoms have primarily formed around a language of flows, connections, and those historical exchanges that have occurred between and across regions. Significantly, China and India are now increasingly framing their civilisational legacies in such terms as they attempt to build alliances and partnerships across the region.

The most notable example of this is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which was launched in 2013. Using the concept of the Silk Road to evoke a narrative of shared pasts and shared futures, China has proclaimed that it is “reviving” historical cultural, religious, and trade ties across Asia, Africa, and southern Europe. It has extended the Silk Road concept beyond trade to include the Health Silk Road and Digital Silk Road. As part of the BRI, China also promoted a “Dialogue of Civilisations” via several high-level multilateral meetings and a multitude of cultural sector initiatives. In March 2023, China’s President Xi Jinping expanded this concept into the Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI), calling for “tolerance, coexistence, exchanges and mutual learning among different civilisations”. The new, re-imagined Silk Road has quickly become one of the key geocultural and geostrategic imaginaries of the 21st Century.

The BRI’s Silk Road imaginary recasts civilisation in two notable ways. First, rather than viewing civilisational pasts in terms of regions on maps, the Silk Road narrative of history places emphasis on “civilisational interactions” along certain routes, or through the connections and flow of ideas, goods, and people across continents and oceans. Second, distinctions between a “unique” Chinese and singular civilisation – that is, humanity – are intentionally blurred. For instance, the GCI is designed to promote the “universal values” of tolerance, peace and harmony required to deal with the global challenges of today.

Not to be outdone, Asia’s other pre-eminent civilisational state, India, has invoked its own civilisational narratives to strengthen ties with strategic partners across the Indian Ocean Region. Project Mausam, which India launched in 2014, is a multilateral strategic alliance for the Indian Ocean which aims to revive a deep history of trade based around monsoon winds, as well as a sensibility about the natural environment. Through such initiatives, India is signalling pre-colonial connections and forms of development as the rationale for 21st Century forms of South-South cooperation. Through their Maritime Silk Road and Project Mausam initiatives, China and India have signalled their eco-civilisational credentials in an attempt to build important platforms of international cooperation around oceans and maritime affairs.

‘Shared Heritage’

This insertion of civilisational legacies as a “shared heritage” of trans-regional connections into foreign policy architectures opens up opportunities for imagining new narratives about past and future. But while both countries proclaim inclusivity and openness in this language of connectivity, China and India continue to view themselves as civilisational “centres”. This raises questions about how smaller countries bordering these “civilisational states” should respond and engage, given the implication that they are often viewed as “lesser”, peripheral regions.

Here, though, South-east Asia has some distinct advantages that enable it to contribute internationally. Connection and exchange lie at the core of the region’s history. Understanding South-east Asia in civilisational terms reveals how a history of flows and connections can be harnessed for peaceful inter-polity relations. The region offers important insights into how different cultural groups can peacefully co-exist, regardless of where political borders might be drawn. Hence, as both China and India proclaim their past offers guidance for addressing global challenges, an understanding of South-east Asia’s distinct cultural, religious, and maritime histories also needs to be mobilised. In a region where hierarchies of core and periphery are far less pronounced, insights can be made into the ways in which these buzzwords of contemporary foreign policy, “mutual respect” or “people to people dialogue” can be historically substantiated.

South-east Asia’s deep cultural and historical interconnections with China and India have created a cultural infrastructure upon which peaceful, mutually beneficial relations can be built across institutions and societal groups. In East Asia, governments, foundations, and universities have long invested in forms of heritage diplomacy that successfully build ties between countries and regions. In South-east Asia, there is significant scope for greater institutional representation and collaboration, such that Asean and government ministries help provide the diplomatic and funding platforms required for meaningful cooperation.

South-east Asia has a distinct contribution to make in shaping how we understand civilisational legacies and their role in the affairs of the 21st Century. It is a region where the past reveals the all-important social and political benefits that arise from defining abstract terms like culture and civilisation in terms of commonalities, rather than differences. The catastrophic events of this century testify to the dangers of defining civilisations as bounded regions or cultures, whereby lines of division constructed in ideological or religious terms emerge as the contours of violent conflict. Undoubtedly, new civilisational imaginaries are required for a peaceful century, especially since peaceful internationalism and international cooperation are fundamentally important if we are to address the key challenges of today. In this regard, South-east Asia has much to offer, especially if relations between China and India remain difficult.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Latest

US-China rivalry will be stern test for Vietnam's diplomatic juggle

Nguyen Cong Tung

Coexistence: The only realistic path to peace

Stephen M. Walt

Cyclone Mocha in conflict-ridden Myanmar is another warning to take climate security seriously

Sarang Shidore

Doubts about AUKUS

Hugh White

Averting the Grandest Collision of all time

Graham Allison

India Can Still Be a Bridge to the Global South

Sanjaya Baru

U.S.-China Trade and Investment Cooperation Amid Great Power Rivalry

Yuhan Zhang

Managing expectations: Indonesia navigating its international roles

Shafiah F. Muhibat

Caught in the middle? Not necessarily Non-alignment could help Southeast Asian regional integration

Xue Gong

It’s Dangerous Salami Slicing on the Taiwan Issue

Richard W. Hu

Navigating Troubled Waters: Ideas for managing tensions in the Taiwan Strait

Ryan Hass

The EU and ASEAN: Partners to Manage Great Power Rivalry?

Tan York Chor

Countering Moro Youth Extremism in the Philippines

Joseph Franco

India-China relations: Getting Beyond the Military Stalemate

C. Raja Mohan

America Needs an Economic Peace Strategy for Asia

Van Jackson

India-Pakistan: Peace by Pieces

Kanti Bajpai

HADR as a Diplomatic Tool in Southeast Asia-China Relations amid Changing Security Dynamics

Lina Gong

Technocratic Deliberation and Asian Peace

Parag Khanna

Safer Together: Why South and Southeast Asia Must Cooperate to Prevent a New Cold War in Asia

Sarang Shidore

Asia, say no to Nato: The Pacific has no need of the destructive militaristic culture of the Atlantic alliance

Kishore Mahbubani

Can Biden bring peace to Southeast Asia?

Dino Djalal

An India-Pakistan ceasefire that can stick

Ameya Kilara

An antidote against narrow nationalism? Why regional history matters

Farish A Noor

Can South Asia put India-Pakistan hostilities behind to unite for greater good?

Ramesh Thakur

Nuclear Deterrence 3.0

Rakesh Sood

The Biden era: challenges and opportunities for Southeast Asia

Michael Vatikiotis