Building a process of trust between India and Pakistan on Kashmir

By Kamila Hak

The second placed entry for the UWCSEA-APP Peace Essay Competition.

JUNE, 2, 2022

Pakistan and India have had three wars in over 70 years. Beginning with the issue of religion and stemming into issues of resource distribution, relations between these two states are yet to find a way into friendly territory. Kashmir has been a continual reason for the mistrust between the two regions as both want access to the resources that Kashmir offers. In this essay, I will examine the historical context and tension between India and Pakistan and propose policies that can be implemented to improve the ongoing conflict.

The partition of Pakistan and India took place on August 14, 1947. This boundary was drawn up by a British man, Cyril Radcliffe, based on which religion dominated each area. Although Kashmir had a Muslim majority, the Maharaja, Hari Singh, was Hindu and therefore had the final say whether Kashmir would join Pakistan or India. He instead decided that he wanted Kashmir to be independent and away from the conflict between both states. This caused an uproar against the Maharaja which was followed by the invasion of Kashmir by Pakistani tribesmen in hopes of taking over the city of Srinagar by looting and raiding it. Maharaja Singh then made a plea to India for their military to help fight back against them and ended up ceding to India while doing so. This caused the first war between India and Pakistan. Nearing the end of 1948, a ceasefire agreement came into place and a de facto border was fixed, claiming two-thirds of Kashmir to India and one-third to Pakistan. Nearing the end of 1948, a ceasefire agreement came into place and a border (later termed the Line of Control, or LoC) was fixed. The violence that occurred during these years began the hostility that is seen within both countries to this day. Two other wars followed in 1965 and 1999 due to clashes within the border. Since 2003, both countries have held an uneasy ceasefire, although there is frequent firing across the LoC.

The question of how India and Pakistan can end this conflict continues to remain complex as both countries have a deep-seated mistrust that is not easy to dismantle. A driving factor behind Pakistan’s interest in Kashmir is the natural resources that Kashmir provides, specifically the Indus river that runs through it. Pakistan fears that India will cut off their access to the water source, which they are largely dependent on, if India has full control over Kashmir. This could immobilise Pakistan’s agriculture as well as instigate droughts. On the other side of the conflict, another reason India wants control over Kashmir is that it gives India a gateway to Central Asia. Without it, there is no land entry to Central Asia. With this in mind, it feels wrong for one country to have full control over this land which has been deemed necessary for success. By holding control of Kashmir, either Pakistan or India would gain immense power over the other instead of working together towards lasting peace. Therefore, Kashmir should have full autonomy over its own natural resources and be able to form its own legislature by re-instating Article 35A. Giving Kashmir power over themselves would most probably anger India and Pakistan. However, a good indication of a fair ruling is if both countries are either upset or if both countries are happy. The outcome of giving Kashmir autonomy has the potential to result in economic success as Kashmir could become a popular tourist destination which could help them form a strong military as well as relations with other countries.

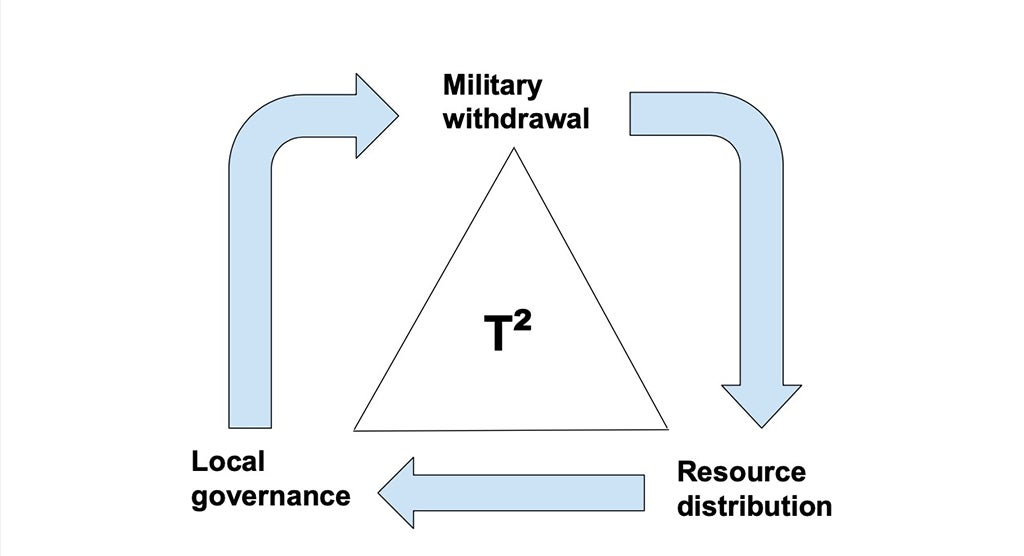

Perhaps the route to finding a permanent solution is punctuated by a series of short-term measures. These short-term measures would be in three broad themes. Firstly, there needs to be military withdrawal from both sides, as mandated by the UN in 1949. Secondly, Kashmir needs to have local governance with grassroots issues and priorities forming the policy and governance of the state. Thirdly, there needs to be a clear policy guiding resource distribution, including water.

This can be thought of as three corners of a triangle which would greatly catalyse the much-needed trust-building, and also unlock the massive tourist and handicraft potential of Kashmir. This ‘Trust Triangle’ (T2) reinforces each element and could lead to long term solutions that come from the Kashmiri people themselves.

Besides this, there are some other factors to be noted. The element of China-controlled Kashmir territory also needs to be drawn into the equation. Also, not to lose sight of the bigger picture, this trust-building also needs to happen along the rest of the border areas that include Sindh and Punjab on the Pakistan side, and Rajasthan, Gujarat and East Punjab on the Indian side.

One option to explore is to re-visit the trade agreements between the two countries - this will not only involve governments but also people-to-people contact. For example, in 1996, India granted Pakistan the most favoured nation status (MFN) but Pakistan did not reciprocate. If Pakistan were to reciprocate this status to India, it would not only make trade across their border faster but also strengthen their trust within each other. This trade facilitation measure is important as it has the potential to decrease poverty and hunger in both countries.

In closing, India and Pakistan need to work on a series of trust-building measures that take into account all three corners of T2 and the communication protocol to draw all stakeholders into the process. This triangle includes military withdrawal, local governance and clear resource distribution. Moreover, Pakistan and India’s trust can be aligned through economic factors such as stronger trade agreements which would not only provide the potential for economic growth but can also increase the overall well-being of citizens in both countries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Latest

Investing in Peace for Asia

Wu Ye-Min

Where are the peacemakers?

Kishore Mahbubani

Can the Belt and Road Initiative bring peace to China and ASEAN?

Selina Ho

America Needs an Economic Peace Strategy for Asia

Van Jackson

India-Pakistan: Peace by Pieces

Kanti Bajpai

HADR as a Diplomatic Tool in Southeast Asia-China Relations amid Changing Security Dynamics

Lina Gong

Technocratic Deliberation and Asian Peace

Parag Khanna

Safer Together: Why South and Southeast Asia Must Cooperate to Prevent a New Cold War in Asia

Sarang Shidore

Freeze, Talk and Trade: the 3 Principles of Peace

Kishore Mahbubani

China and India: More New Diplomacy

Kumar Ramakrishna

Countering the threat of Islamist extremism in Southeast Asia

Kumar Ramakrishna

Asia, say no to Nato: The Pacific has no need of the destructive militaristic culture of the Atlantic alliance

Kishore Mahbubani

Can Biden bring peace to Southeast Asia?

Dino Djalal

An India-Pakistan ceasefire that can stick

Ameya Kilara

An antidote against narrow nationalism? Why regional history matters

Farish A Noor

The Anchorage Meeting Will Buy America Needed Time

Douglas Paal

The oxygen of ASEAN

Kishore Mahbubani

Beware of Munich

Khong Yuen Foong

Can South Asia put India-Pakistan hostilities behind to unite for greater good?

Ramesh Thakur

Nuclear Deterrence 3.0

Rakesh Sood

The Biden era: challenges and opportunities for Southeast Asia

Michael Vatikiotis

Islamist Terrorism in Indonesia: Roots and Responses

Noor Huda Ismail

Can Asians speak truth to power?

Hugh White

How China and the U.S. Can Avoid a Clash in the South China Sea.

Mark J. Valencia

China and Japan: Will They Ever Reconcile?

Tommy Koh

China and India: A New Diplomacy

Kanti Bajpai