Southeast Asia, China, and the Belt and Road Initiative: Still Going Strong?

By Guanie Lim

Guanie Lim is an Assistant Professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Japan.

MAY, 15, 2024

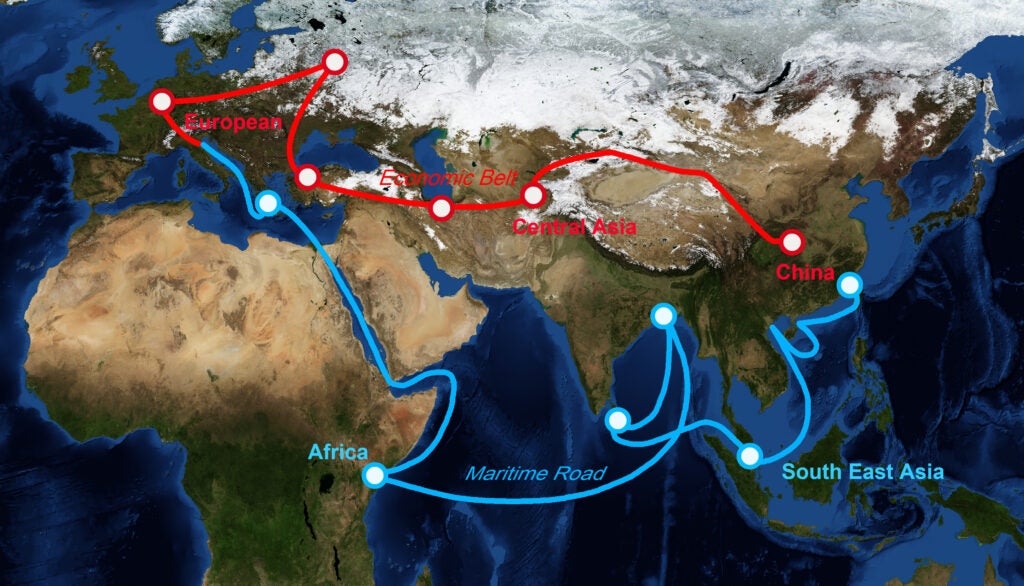

Relations between great powers and their neighboring regions are often fraught. The cases of the United States and Latin America, or the European Union and North Africa, come to mind. For instance, tensions related to immigration from Latin America and North Africa, has led to the rise of right wing populism in the United States and Europe, respectively. This has fueled the rise of populist politicians such as Donald Trump in the United States and Marine Le Pen in France. In China’s case, economic engagement has helped to stabilize and strengthen its relationship with Southeast Asian countries, despite ongoing disputes in the South China Sea. One important facet of this engagement is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which China launched 11 years ago.

Most of the Southeast Asian countries do not have the means to fund major infrastructure projects, resulting in an infrastructure deficit in the region. Chinese investments, including those of the BRI, have thus become an important economic force in Southeast Asia. The reality is that very few economies have matched Chinese business groups’ appetite in pushing infrastructure projects, especially capital- and technology-intensive ones which take a long time to produce returns. While other players have attempted to promote infrastructure building and other forms of cooperation in Southeast Asia, such as the EU’s Global Gateway, there is considerable room for improvement. By contrast, Chinese firms have managed to deliver some of the most challenging projects in the region. Two recent examples come to mind: the Boten-Vientiane railway in Laos and the Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail in Indonesia. The generally positive reception to these projects since their opening has likely increased the appeal of similar initiatives to the public.

Indonesia’s experience in opting for China (over Japan) for its landmark railway project is worth discussing. The Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail was one of the most heavily criticized Chinese projects before and during its construction. Despite some delays and dissenting voices along the way, the project began commercial operations in late 2023. Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) and Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Pandjaitan are evidently satisfied enough with the project’s outcome to want to continue cooperating with the state-owned China Railway Group Limited (CREC) to extend the railway service to Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-biggest city. The Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail has allowed Indonesian policymakers to address longstanding issues, such as the challenging task of setting up development links between Jakarta and smaller urban hubs. And, importantly, working on this project has enhanced the organizational capabilities of the Indonesian central and local governments, which will help them manage other complex undertakings in the future.

In Vietnam, ties with China have generally been cordial. Notwithstanding reservations in some quarters over the economic domination of China, the reality is a lot more nuanced. For one, Vietnam has harnessed the investment dollars of transnational corporations de-risking from China, transforming itself into a ‘connector economy’ interlinking the US and Chinese markets. There is another subtext here – the influx of investment and businesses triggered by the US-China competition adds positive momentum to Vietnam’s attempts to continue and even deepen the pro-market reforms it first initiated in 1986. Vietnam and China are currently in the midst of exploring strengthening rail and road infrastructure and connectivity between the Yunnan province in China and Vietnam (including Hanoi and the port city of Haiphong), through the BRI initiative.

It is true that some of China’s ‘Going Out’ efforts have fallen short of their initial aims. Reasons for this range from political pushback in certain host economies to overoptimistic financial projections. This has led to adjustments, resulting in a shift towards “smaller, greener, and more beautiful” undertakings and projects centered on knowledge and technology, rather than resource- and labor-intensive endeavors. In addition, ad-hoc deals are transitioning towards more institutionalized arrangements, especially after the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) was established in 2018. The CIDCA represents an institutional innovation to harmonize efforts across multiple state organs, with the overarching goal of implementing and overseeing development aid projects more effectively. These transitions, while not usually mentioned in the popular media, underline an important reality of economic cooperation: real and consequential changes often happen slowly and subtly, hidden far in the background.

It is reasonable to expect some occasional pit-stops as the BRI heads into its second decade in Southeast Asia. The key lies in exploring common platforms to further Southeast Asia-China cooperation. At the same time, it is important to avoid sweeping, oversimplified caricatures of Chinese capital exports. A more balanced perspective, which takes account of context-specific issues in the host economies and the region’s wider economic architecture, would be more fruitful.

Great powers and their neighbors share a common interest in fostering regional peace, prosperity, and political and economic stability. China has been instrumental in meeting the pressing need in Southeast Asia for infrastructure development through the BRI, and it has in turn reaped political and economic dividends. Economic interdependence has also raised the costs of potential regional conflict. The role of the BRI in managing the China-Southeast Asia relationship could serve as a valuable model for study for other great power-neighborhood relations, such as those between the United States and Latin America and between the European Union and North Africa.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Latest

Reconceptualizing Asia's Security Challenges

Jean Dong

Asia should take the Lead on Global Health

K. Srinath Reddy and Priya Balasubramaniam

Rabindranath Tagore: A Man for a New Asian Future

Archishman Raju

Securing China-US Relations within the Wider Asia-Pacific

Sourabh Gupta

Biden-Xi summit: A positive step in managing complex US-China ties

Chan Heng Chee

Singapore's Role as Neutral Interpreter of China to the West

Walter Woon

The US, China, and the Philippines in Between

Andrea Chloe Wong

Crisis Management in Asia: A Middle Power Imperative

Brendan Taylor

America can't stop China's rise

Tony Chan, Ben Harburg, and Kishore Mahbubani

Civilisational Futures and the Role of Southeast Asia

Tim Winter

US-China rivalry will be stern test for Vietnam's diplomatic juggle

Nguyen Cong Tung

Coexistence: The only realistic path to peace

Stephen M. Walt

Cyclone Mocha in conflict-ridden Myanmar is another warning to take climate security seriously

Sarang Shidore

Doubts about AUKUS

Hugh White

Averting the Grandest Collision of all time

Graham Allison

India Can Still Be a Bridge to the Global South

Sanjaya Baru

U.S.-China Trade and Investment Cooperation Amid Great Power Rivalry

Yuhan Zhang

Managing expectations: Indonesia navigating its international roles

Shafiah F. Muhibat

Caught in the middle? Not necessarily Non-alignment could help Southeast Asian regional integration

Xue Gong

It’s Dangerous Salami Slicing on the Taiwan Issue

Richard W. Hu

Navigating Troubled Waters: Ideas for managing tensions in the Taiwan Strait

Ryan Hass

The EU and ASEAN: Partners to Manage Great Power Rivalry?

Tan York Chor

Countering Moro Youth Extremism in the Philippines

Joseph Franco

India-China relations: Getting Beyond the Military Stalemate

C. Raja Mohan

America Needs an Economic Peace Strategy for Asia

Van Jackson

India-Pakistan: Peace by Pieces

Kanti Bajpai

HADR as a Diplomatic Tool in Southeast Asia-China Relations amid Changing Security Dynamics

Lina Gong

Technocratic Deliberation and Asian Peace

Parag Khanna

Safer Together: Why South and Southeast Asia Must Cooperate to Prevent a New Cold War in Asia

Sarang Shidore

Asia, say no to Nato: The Pacific has no need of the destructive militaristic culture of the Atlantic alliance

Kishore Mahbubani

Can Biden bring peace to Southeast Asia?

Dino Djalal

An India-Pakistan ceasefire that can stick

Ameya Kilara

An antidote against narrow nationalism? Why regional history matters

Farish A Noor

Can South Asia put India-Pakistan hostilities behind to unite for greater good?

Ramesh Thakur

Nuclear Deterrence 3.0

Rakesh Sood

The Biden era: challenges and opportunities for Southeast Asia

Michael Vatikiotis