Southeast Asia’s “Anatomy of Choice” Between the Great Powers

Joseph Chinyong Liow is Dean of the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Yuen Foong Khong is Li Ka Shing Professor of Political Science at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.

Republished in South China Morning Post, Anatomy of choice: why Southeast Asia is aligning with China | South China Morning Post

September 5, 2025

As differences between China and the United States harden further into strategic rivalry, the question of choice - between either of the two great powers – continues to loom large over the countries of Southeast Asia. To be sure, regional leaders have consistently repeated the refrain that they do not wish to have to choose sides between the two. For their part, both Chinese and American leaders have often claimed that they do not wish to foist a choice upon regional states. But the attitudes of the two great powers appears to be changing. Against the backdrop of his “Liberation Day” tariff policy and with an eye towards preventing transshipment, U.S. president Donald Trump has already made clear that any country that wishes to secure a trade deal with the U.S. must pivot its trading relations away from China. He has also threatened to impose additional tariffs on countries that are part of the BRICS, which he considers an “anti-U.S.” bloc. Correspondingly, Chinese president Xi Jinping has warned countries against pursuing trade deals that sideline China.

Anatomy of Choice

Notwithstanding the strategic dilemma these ultimatums create for Southeast Asia, the fact is that states make choices all the time: for instance, whether to sign an economic agreement or join a multilateral organisation, or who to procure defence equipment from. The question really is not choice per se, but why choices are made in the context of strategic competition between great powers, and what an aggregation of choices tell us about alignments. A recently concluded project we helmed—supported by a Singapore Social Science Thematic Grant-- collected data and analysed the choices of the ten Southeast Asian states in relation to the U.S. and China to form the Anatomy of Choice Alignment Index (AOCAI). This involves a dataset of 20 indicators over a period of 30 years (1995-2024). These 20 indicators are further grouped into five domains: Political-Diplomatic, Military-Security, Economics-Trade, Soft Power, and Signalling. (For details see https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/cag/research/international-relations-of-southeast-asia)

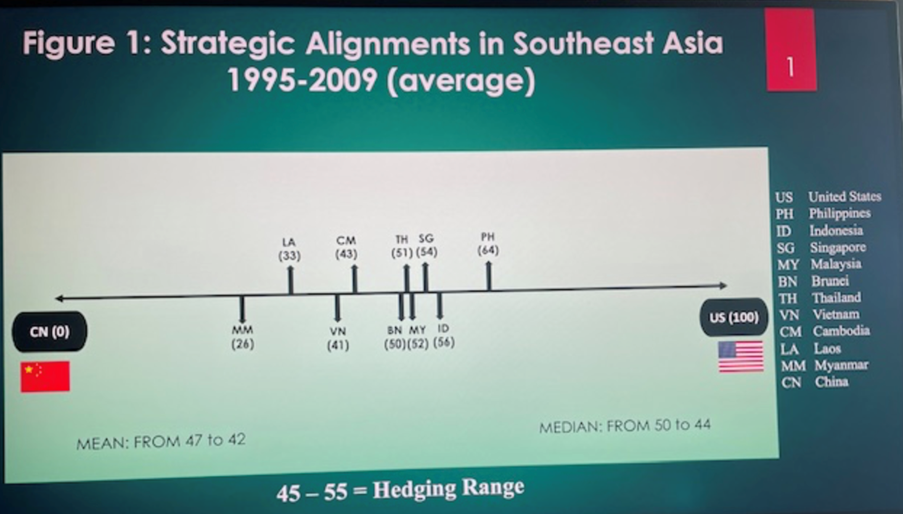

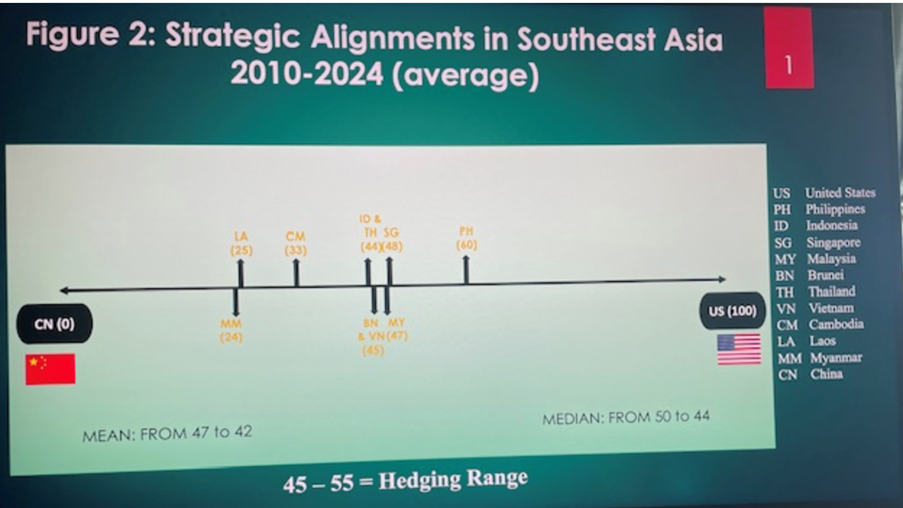

The main finding of the project is this: while most Southeast Asian states remain clustered in the centre of a U.S.-China continuum, there has been a gradual but clear movement away from the U.S. and toward China over a thirty-year period. This can be seen by comparing Figures 1 and 2 below, which disaggregate the thirty-year period into two fifteen year time spans: the comparison suggests that the alignment scores of most countries have moved leftwards, toward China. Some countries have moved more significantly toward China, while others, despite moving in the same direction, have maintained their “clustering around the middle” position.

Figure 1: 1995-2009

Figure 2: 2010-2024

This is not to say that the overall alignment positions of these Southeast Asian states are a result of deliberate, intentional, or strategic choices. Indeed, in some cases they are not. Choices have tended to be made in a la carte fashion depending on the issue at hand, and in accordance to the interests of the Southeast Asian state. As Singapore prime minister Lawrence Wong described: “[In] some instances, we may make decisions that seems to favour one side versus the other; but that does not mean that we are pro-China or pro-America. It simply means that we are pro-Singapore” (he made those remarks in October 2023, in his capacity as deputy prime minister).

What Explains These Alignment Moves?

From our analysis, four key factors stand out: domestic politics, economic opportunities, estimation of U.S. staying power, and geography. The most significant - by which we mean the greatest variation over the thirty years - has been economic opportunities, where, from a low base in the mid-1990s, China has emerged as a major provider of economic opportunities for Southeast Asia. For at least the last decade (if not more), China has been the largest trading partner of practically every Southeast Asian state. Regardless of its flaws and shortcomings, the Belt and Road Initiative, introduced by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2017, has been embraced across the region, with multiple BRI projects underway particularly in mainland Southeast Asia, underwritten by Chinese loans. This has taken place commensurate with the swift development of China’s own economy and its climb up the technology value chain.

In the case of China, economic opportunities are tied very closely to geography. Most analysts agree that the countries of mainland Southeast Asia have grown more dependent on China economically over the last decade or so, and geographic proximity plays a large part in explaining that. Perhaps the most profound example of is to be found in the political economy of the Mekong region. As the uppermost riparian state, China can – and does - control the flow of the most important river in Southeast Asia, the Mekong, which serves as the lifeblood of large agrarian communities of lower riparian regional states such as Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam that are concentrated along the river and in its basin. More than 10 dams built on the Mekong by China attest to this influence.

By comparison, the U.S. is seen as a geographically distant power. No doubt, this has not prevented America from playing an important stabilizing role as an offshore balancer. Yet the stark reality is that distance cannot but prompt concern for the reliability and sustainability of the U.S. commitment to regional security. Indeed, one of the recurrent questions posed at numerous conferences on the South China Sea is whether the U.S. would in fact risk open conflagration with China over a collection of disputed reefs, rocks, and shoals more than 12000km away.

Finally, domestic politics, conceived in terms of change in governments and regime legitimation, are also key to understanding alignment patterns. Whether in the Philippines, where China policy has vacillated according to who occupies the presidency, in Malaysia, where anti-U.S. sentiments are regularly stoked by both incumbent and opposition leaders, or in Indonesia, where engagement with China is shaped by elite bargaining, these manifestations of domestic politics have played a prominent role in determining policy choices of Southeast Asian states in relation to the two great powers.

The ASEAN Factor

The research project on which this short essay is based did not explicitly focus on ASEAN, the regional organization which brings together the ten states of Southeast Asia. Indeed, the focus was very much on how each individual Southeast Asian state has been approaching its bilateral relations with the U.S. and China in the last three decades, and what this tells us about their alignment choices.

ASEAN fulfils an important, albeit different, function for regional states when it comes to engagement with the superpowers. To be sure, the organization and its various “ASEAN-led” mechanisms, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum, ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus, East Asia Summit, and ASEAN meetings with dialogue partners, of which the U.S. and China are a part, all offer additional avenues through which regional states have engaged the superpowers. But these are “additional” avenues, as opposed to “primary”. The reality is that, as much as ASEAN mechanisms have proven useful, regional states have prioritized bilateral engagements in relations with the U.S. and China. This was evident, for instance, in the inability of ASEAN to pursue a united effort to negotiate tariffs with the Trump administration. Likewise, while Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim should be congratulated for parlaying the ASEAN chairmanship this year to help bring about an end to the Thailand-Cambodia conflict that had recently been reignited over their competing claims over the areas surrounding the Preah Vihear Temple, it is difficult to imagine how the effort could have been as swift and effective as it was if not for the warnings of President Trump that he would not entertain negotiation on tariffs with either of the conflict parties unless they brought an end to hostilities. In other words, while ASEAN may have provided the venue, it was the U.S. that provided the impetus.

The Road Ahead

Rivalry and competition between the U.S. and China show no signs of abating. If anything, it is likely to grow in intensity and complexity, and possibly, be more dangerous than the U.S.-Soviet competition of the Cold War. Southeast Asia will be a major arena where this contest will play out. While it is unclear how things might unfold in the long-term, what is clear over the short-term is this: should the second Trump administration persist in its current approach of imposing hefty tariffs on Southeast Asian states while demanding that they distance themselves economically from China, the direction of travel identified in the AOCAI is likely to continue, if not accelerate.

The thirty year timeline of the AOCAI ends in 2024, just before the return of Donald Trump to the White House. We wager that the Trump administration’s approach to Southeast Asia, in particular its tariff policies, is likely to accentuate the region’s strategic drift away from the U.S., toward China. This is not to say that there will not be efforts on the part of regional states to maintain relations with the U.S. For instance, Cambodia has nominated President Donald Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts at resolving the Thai-Cambodia border conflict (it is interesting to note that it was President Trump, not ASEAN nor Anwar Ibrahim, who was nominated) despite the fact that it is more closely aligned with China. It is important to bear in mind, however, that the Cambodian gesture is but an isolated data point, whereas our research is interested in larger processes that have unfolded over decades.

The US and China are locked in a rivalry defined by strategic competition in practically all domains. This dynamic will remain the single-most consequential factor determining global peace and stability in the foreseeable future. Whether Southeast Asian states like it or not, their region is already an arena of great power rivalry. The pressures to choose will only increase and understanding the anatomy of choice (of the Southeast Asian states) is a vital step in shoring up regional resilience.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Latest

Integrated Supply Chains - A Posible Citadel for Peace in Southeast Asia

by Cameron Johnson

How to Fix the Cracks in the Nuclear Dam

by Adam Thomson

Persuading for Peace, Protecting Its Interests: China’s Conflict Diplomacy

by Andrew Cainey and Chengkai Xie

US ASEAN Policy Must Be Rooted in Economics, Not Just Defense

by Abhinav Seetharaman

South Korea: Is it time for a more balanced strategy?

by Soon Ok-Shin

A nuclear war started by AI sounds like sci-fiction. It isn’t

by Sundeep Waslekar

Ports, politics, and peace: The engineering of stability

by Guru Madhavan

It's Time for Europe to Do the Unthinkable

Kishore Mahbubani

Can Young Americans and Chinese Build Bridges Over Troubled Waters?

Brian Wong

Trump 2:0: Getting US-China ties right despite the odds

Zhiqun Zhu

How Malaysia can boost Asean agency and centrality amid global challenges

Elina Noor

Why India-Pakistan relations need a new era of engagement

Farhan Hanif Siddiqi

Reconceptualizing Asia's Security Challenges

Jean Dong

Asia should take the Lead on Global Health

K. Srinath Reddy and Priya Balasubramaniam

Rabindranath Tagore: A Man for a New Asian Future

Archishman Raju

Securing China-US Relations within the Wider Asia-Pacific

Sourabh Gupta

Biden-Xi summit: A positive step in managing complex US-China ties

Chan Heng Chee

Singapore's Role as Neutral Interpreter of China to the West

Walter Woon

The US, China, and the Philippines in Between

Andrea Chloe Wong

Crisis Management in Asia: A Middle Power Imperative

Brendan Taylor

America can't stop China's rise

Tony Chan, Ben Harburg, and Kishore Mahbubani

Civilisational Futures and the Role of Southeast Asia

Tim Winter

US-China rivalry will be stern test for Vietnam's diplomatic juggle

Nguyen Cong Tung

Coexistence: The only realistic path to peace

Stephen M. Walt

Cyclone Mocha in conflict-ridden Myanmar is another warning to take climate security seriously

Sarang Shidore

Doubts about AUKUS

Hugh White

Averting the Grandest Collision of all time

Graham Allison

India Can Still Be a Bridge to the Global South

Sanjaya Baru

U.S.-China Trade and Investment Cooperation Amid Great Power Rivalry

Yuhan Zhang

Managing expectations: Indonesia navigating its international roles

Shafiah F. Muhibat

Caught in the middle? Not necessarily Non-alignment could help Southeast Asian regional integration

Xue Gong

It’s Dangerous Salami Slicing on the Taiwan Issue

Richard W. Hu

Navigating Troubled Waters: Ideas for managing tensions in the Taiwan Strait

Ryan Hass

The EU and ASEAN: Partners to Manage Great Power Rivalry?

Tan York Chor

Countering Moro Youth Extremism in the Philippines

Joseph Franco

India-China relations: Getting Beyond the Military Stalemate

C. Raja Mohan

America Needs an Economic Peace Strategy for Asia

Van Jackson

India-Pakistan: Peace by Pieces

Kanti Bajpai

HADR as a Diplomatic Tool in Southeast Asia-China Relations amid Changing Security Dynamics

Lina Gong

Technocratic Deliberation and Asian Peace

Parag Khanna

Safer Together: Why South and Southeast Asia Must Cooperate to Prevent a New Cold War in Asia

Sarang Shidore

Asia, say no to Nato: The Pacific has no need of the destructive militaristic culture of the Atlantic alliance

Kishore Mahbubani

Can Biden bring peace to Southeast Asia?

Dino Djalal

An India-Pakistan ceasefire that can stick

Ameya Kilara

An antidote against narrow nationalism? Why regional history matters

Farish A Noor

Can South Asia put India-Pakistan hostilities behind to unite for greater good?

Ramesh Thakur

Nuclear Deterrence 3.0

Rakesh Sood

The Biden era: challenges and opportunities for Southeast Asia

Michael Vatikiotis